Stopping Spyware at the Gate:

A User Study of Privacy, Notice and Spyware

Nathaniel Good

1

, Rachna Dhamija

1

, Jens Grossklags

1

, David Thaw

1

, Steven Aronowitz

2

,

Deirdre Mulligan

2

, Joseph Konstan

3

{ngood,rachna,jensg,dbthaw}@ sims.berkeley.edu

dmulligan@law.berkeley.edu, stevenaronowi[email protected], konstan@cs.umn.edu

1

School of Information Management

and Systems, UC Berkeley

102 South Hall

Berkeley, CA 94720

2

Samuelson Law, Technology &

Public Policy Clinic

Boalt Hall (School of Law)

UC Berkeley

Berkeley, CA 94720

3

Department of Computer Science

University of Minnesota

4-192 EE/CS Building

Minneapolis, MN 55455

ABSTRACT

Spyware is a significant problem for most computer users. The

term “spyware” loosely describes a new class of computer

software. This type of software may track user activities online

and offline, provide targeted advertising and/or engage in other

types of activities that users describe as invasive or undesirable.

While the magnitude of the spyware problem is well documented,

recent studies have had only limited success in explaining the

broad range of user behaviors that contribute to the proliferation

of spyware. As opposed to viruses and other malicious code,

users themselves often have a choice whether they want to install

these programs.

In this paper, we discuss an ecological study of users installing

five real world applications. In particular, we seek to understand

the influence of the form and content of notices (e.g., EULAs) on

user’s installation decisions.

Our study indicates that while notice is important, notice alone

may not be enough to affect users’ decisions to install an

application. We found that users have limited understanding of

EULA content and little desire to read lengthy notices. Users

found short, concise notices more useful, and noticed them more

often, yet they did not have a significant effect on installation for

our population. When users were informed of the actual contents

of the EULAs to which they agreed, we found that users often

regret their installation decisions.

We discovered that regardless of the bundled content, users will

often install an application if they believe the utility is high

enough. However, we discovered that privacy and security

become important factors when choosing between two

applications with similar functionality. Given two similar

programs (e.g., KaZaA and Edonkey), consumers will choose the

one they believe to be less invasive and more stable. We also

found that providing vague information in EULAs and short

notices can create an unwarranted impression of increased

security. In these cases, it may be helpful to have a standardized

format for assessing the possible options and trade-offs between

applications.

Categories and Subject Descriptors

H.5.2 [Information Interfaces and Presentation]: User

Interfaces: interaction styles, standardization, user-centered

design

J.4 [Social and Behavioral Sciences]: psychology

K.4.1 [Computers and Society]: Public Policy Issues - privacy

and regulation

K.5.2 [Legal Aspects of Computing]: Governmental Issues –

regulation

General Terms

Design, Experimentation, Security, Human Factors, Legal

Aspects.

Keywords

Privacy, Notice, End User License Agreement, EULA, Security

and Usability, Spyware, Terms of Service, ToS

1. INTRODUCTION

Spyware is a significant problem for most computer users. The

term “spyware” loosely describes a new class of computer

software. This type of software may track users’ activities online

and offline, provide targeted advertising, and/or engage in other

types of activities that users describe as invasive or undesirable.

Data suggests that these types of programs may reside on up to 90

percent of all Internet-connected computers [10]. Frequently,

programs bundle spyware with freeware or shareware, though it

can also arrive via email, instant messages or web downloads.

While the magnitude of the spyware problem is well documented

recent studies have had only limited success in explaining the

broad range of user behaviors that contribute to the proliferation

of spyware. As opposed to viruses and other malicious code,

users themselves often have a choice whether they want to install

these programs. Anecdotal evidence suggests, and our study

confirms, that some users are willing to install spyware when the

desired application is of perceived high utility and a comparable

product without spyware is not available or known to the user

Copyright is held by the author/owner. Permission to make digital o

r

hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is

granted without fee.

Symposium On Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS) 2005, July 6-8,

2005, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

1

[21]. Our goals in this study are to understand the factors and

user’s decision making process in installing spyware.

During installation, users are presented with notices such as

software agreements, terms of service (TOS), end user licensing

agreements (EULA), and security warnings. Based on

information in these notices, users should, in theory, be able to

make a decision about whether to install the software and evaluate

the potential consequences of that decision. However, there is a

general perception that these notices are ineffective. One software

provider included a $1000 cash prize offer in the EULA that was

displayed during each software installation, yet the prize was only

claimed after 4 months and 3,000 downloads of the software [16].

In this paper, we discuss a study of users installing five real world

applications in a near natural laboratory setting. The aim of this

ecological study is an in-depth understanding of users’ actions and

motivations when faced with installation decisions on applications

that may contain spyware. In particular, we seek to understand

the influence of the form and content of notices (e.g., EULAs).

The purpose of our study is neither to create a new standard for

notices, nor to evaluate the effectiveness of various language

terms. Rather, our goal is to determine the effect of different

notice conditions on a user installation decisions and their

knowledge of the privacy and security consequences.

Our study highlights the fact that eliminating spyware is not only

a technical challenge. There are also legal, social, economic and

human factors to consider, and none of these factors can be

examined in isolation.

In Section 2, we provide background information about spyware.

In Section 3, we present a summary of related work. We describe

our experimental design in Section 4 and the study results in

Section 5. Finally, we present our conclusions in Section 6 and

plans for future work in Section 7.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1 Definition of Spyware

A fundamental problem is the lack of a standard definition of

spyware. Two particularly contested issues are the range of

software behaviors that should be included in the definition and

the degree of user consent that is desirable.

First, some prefer a narrow definition that focuses on the

surveillance aspects of spyware and its ability to collect, store and

communicate information about users and their behavior. Others

use a broad definition that includes adware (software that displays

advertising), toolbars, search tools, hijackers (software that

redirects web traffic or replaces web content with unexpected or

unwanted content) and dialers (programs that redirect a computer

or a modem to dial a toll phone number). Definitions for spyware

also include hacker tools for remote access and administration,

keylogging and cracking passwords.

Second, there is limited agreement on the legitimacy of spyware

that engages in behavior such as targeting advertisements,

installing programs on user machines and collecting click stream

data. Users consider a wide range of programs that present

spyware-like functionality unacceptable. To complicate the

definition, certain software behaviors are acceptable in some

contexts but not others (e.g., keylogging software installed on an

adult’s private computer without consent may be unacceptable,

while parental control software may be desired). Furthermore,

there is concern over user notice and consent (e.g., in EULA or

ToS) required during an installation process. The practice of

bundling software, which merges spyware with unrelated

programs, also heightens this concern.

2.2 Anti-Spyware Legislation

Spyware legislation is currently under consideration in 27 U.S.

States as well as in the U.S. Congress. The state proposals vary

widely in their breadth of protection, the types of software they

address, and the justifications they assert for State action.

1

The

highlights of proposed legislation in Utah, for example, include

“prohibit[ing] spyware from delivering advertisements to a

computer under certain circumstances… requiring spyware to

provide removal procedures… [and] require[ing] the [State]

Division of Consumer Protection to collect complaints.”

2

Federal

legislation, in contrast, is more concerned with “protect[ing] users

of the Internet from unknowing transmission of their personally

identifiable information through spyware programs.”

3

The distinction between these proposals is representative of the

myriad approaches in proposed legislation and indicates a lack of

a common baseline understanding of the problem. For example,

there is confusion about the applicability of current law to

different types of spyware.

4

Spyware is an interstate and

international problem that could benefit from a common

approach, based on a thorough analysis of the spyware problem.

One of the goals of our research is to contribute to a better

understanding of this problem and to a more thoughtful solution.

2.3 Anti-Spyware Technology

Anti-spyware vendors use a combination of objective

categorization and scoring approaches to decide whether to

include a program in their removal engine. Other criteria include

a history of unacceptable behavior, the quality of notice provided

to users, and expert and user opinions

5

.

Anti-spyware vendors make many individual choices about what

to do with suspected spyware programs. They can choose to

remove them, ignore them or notify the user. Because users

choose to install applications that bundle spyware, simply deleting

all suspected programs may inadvertently cause desired

applications to break. For this reason, many anti-spyware vendors

inform users about possible threats, but ultimately give the

consumer control over what is to be removed.

1

Moll, David C. “State of Spyware Q1 2005.” Available at

http://itpapers.techrepublic.com/thankyou.aspx?compid=17410

&docid=134901&view=134901, pp. 64-68.

2

H.B. 323 “Spyware Regulation.” 2004 General Session, State of

Utah.

3

H.R. 29 In the House of Representatives. 109

th

Congress, 1

st

Session, January 9, 2004.

4

Current actions based on existing laws include the FTC suing

Seismic Entertainment Productions, SmartBot.new, Inc. and

Sanford Wallace; the FTC seeking and receiving a Temporary

Restraining Order against the producers of Spyware Assassin;

and New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer filing the first

civil action against a Spyware provider (Intermix Media, Inc.)

accusing the company of installing software without users’

knowledge that produced pop-up ads and destabilized

computers. See Press Release, Office of New York State

Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, available at

http://www.oag.state.ny.us/press/2005/apr/apr28a_05.html.

5

Examples of anti-spyware include Ad-Aware (www.lavasoft.de),

Pest Patrol (www.ca.com), Spybot (spybot.safer-networking.de)

and Webroot (www.webroot.com). Note, however, that there are

numerous anti-spyware programs with questionable or even

malicious functionality (see:

http://www.spywarewarrior.com/rogue_anti-spyware.htm).

2

3. RELATED WORK

Spyware researchers can be informed by prior work in many

fields. For the purposes of this study, we focus on related work

that examines user behavior and the design and improvement of

notice to the user.

3.1 Privacy Attitudes and User Behavior

Consumers often lack knowledge about risks and modes of

technical and legal protection [3]. For example, a recent

AOL/NSCA study showed that users are unaware of the amount

of spyware installed on their computers and its origin [5]. A

related example is a study on the use of filesharing clients that

shows that users are often unaware that they are sharing sensitive

information with other users [12].

Users also differ in their level of privacy sensitivity. Cranor et. al.

[8] found that consumers fall generally into one of three

categories: privacy fundamentalists, privacy pragmatists, and the

marginally concerned. Other research shows that the pragmatic

group’s attitudes differ towards the collection of personally

identifying information and information to create non-identifying

user profiles [18] and can be distinguished with respect to concern

towards offline and online identity [3]. Users also show great

concern towards bundling practices and the involvement of third

parties in a transaction [3][8].

Experimental research demonstrates that user behavior does not

always align with stated privacy preferences [3][18]. Users are

willing to trade off their privacy and/or security for small

monetary gains (e.g., a free program) or product recommendations

[3][18]. Moreover, Acquisti and Grossklags [3] report evidence

that users are more likely to discount future privacy/security

losses if presented with an immediate discount on a product.

Consumers may also accept offers more often when benefits and

costs are difficult to compare and descriptions are provided in

ambiguous and uncertain terms [4].

3.2 Online Privacy Notices

EULAs, TOS and some privacy policies present complex legal

information. Research shows, however, that complexity of

notices hampers users’ ability to understand such agreements. For

example, Jensen and Pott [15] studied a sample of 64 privacy

policies from high traffic and health care websites. They found

that policies’ format, location on the website and legal content

severely limit users’ ability to make informed decisions.

One attempt to improve users’ ability to make informed decisions

is the Platform for Privacy Preferences Project (P3P) [16]. Under

this standard, websites’ policies are expressed in a predefined

grammar and vocabulary. Ackerman and Cranor [1] explored

ways to provide user assistance in negotiating privacy policies

using semi-autonomous agents to interact with P3P enabled sites.

Another system [7] encourages users to create several P3P-

enabled identity profiles to address information usage patterns and

privacy concerns for different types of online interactions.

3.3 Multi-layered Notices

Research on product labeling and hazard warnings (see, for

example, [14]) focuses on improving the efficiency of consumer

notification.

6

This research has influenced the formulation of

6

The debate over labeling and notice is also taking place in the

area of Digital Rights Management (DRM). DRM systems limit

a consumer’s ability to share copyright protected content

through digital media software and hardware features. Users

implicitly agree to these limits when purchasing DRM equipped

alternative notice concepts. For example, researchers from the

Center for Information Policy Leadership call for statements in

short, everyday language that are available in a common easy-to-

read format

7

. However, they also caution that legal requirements

require companies to provide complete notices that do not fit this

standard (see, for example, [1]). They propose a multi-layered

notice with a minimum of two notices that first provide a

summary at the top level, increasing detail at the lower layers, and

the complete, detailed notice as a final layer. The layering should

include a short notice (also called condensed notice or highlights)

that provides the most important information in a consistent

format, including the parties involved, contact information, and

the type of data collected and the uses for which it is intended.

There is varying governmental support for layered notices. For

example, the European Union has taken concrete steps towards a

layered notice model.

8

In the United States, the Department of

Health and Human Services has encouraged entities covered by

the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

to prepare such notices [13]. However, despite public

consideration

9

, there is no broad consensus for the financial

industry pursuant to the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act [1].

3.4 Notification Systems

A number of researchers are studying the effects of notification

systems in computing. Examples of systems include instant

messaging, user status updates, email alerts, and news and stock

tickers. This research examines the nature of interruptions and

people’s cognitive responses to work-disruptive influences.

Notification systems commonly use visualization techniques to

increase information availability while limiting loss of users’

focus on primary tasks [6][9][20].

4. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

We conducted an ecological study of users installing five real

world applications. Our goal is to examine the factors that

contribute to users decisions to install applications that contain

spyware. In particular, we seek to understand how the form and

content of notices affects users’ decisions to install spyware and

their knowledge of the privacy and security consequences. The

goals of our investigation required us to observe user actions as

they installed actual programs with bundled spyware.

products. Some consumer advocates believe this kind of implicit

notice is not adequate to alert consumers to the reduced

functionality of the product they are purchasing. In 2003 Reps

Boucher (D-VA), Lofgren (D-CA) and Brownback (R-KS)

introduced the Consumers, Schools and Libraries Digital Rights

Management Awareness Act which attempted to increase

consumer DRM rights.

7

P3P clearly shares the same goals, however, with a somewhat

complementary solution process.

8

The Article 29 Data Protection Working Party (an independent

advisory body set up under Article 29 of Directive 95/46/EC)

outlined this approach in the November 25, 2004 Opinion on

More Harmonised Information Provisions Available at:

http://europa.eu.int/comm/internal_market/privacy/docs/wpdocs

/2004/wp100_en.pdf.

9

See notes from a public workshop to discuss how to provide

effective notice under the GLB Act: Get Noticed: Effective

Financial Privacy Notices, (Dec. 4 2001) at

http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/workshops/glb/.

3

An alternative design would be to record users’ actions on their

own machines over some period of time and ask users questions

about the types of programs they installed. However, this

approach is error-prone, as it depends upon users correctly

remembering and commenting on their actions. Furthermore, it

raises substantial privacy concerns for the users.

An audit of user machines (e.g., the methodology employed in the

Earthlink spyware audit [10]) would allow us to discover the

programs on user machines, however it would not provide a way

to study the reasons for their behavior. The advantages of the

ecological study approach is that we were able to obtain sufficient

data, observe all interactions with the software, gather qualitative

data about the decision-making process during and after

installation and maintain consistency across subjects.

4.1 Experiment Construction

4.1.1 Applications Used in the Experiment

As part of our ecological study, we selected five applications that

users could download. Each contained bundled software or

functionality that monitored user’s actions or displayed ads. The

criteria we used in selecting our programs were:

1) the program must have a legitimate and desirable function;

2) the program must have included or bundled functionality that

may be averse to a given user’s privacy/security preferences;

and

3) the product must have a pre-installation notice of terms that

the user must consent to in order to install the application.

Additionally, we wanted the programs to reflect the range of

behavior, functionality and reputation that users encounter while

installing applications in the real world. We selected some

programs that had explicit opt-out options (e.g., Google Toolbar

and Edonkey) and some that did not have explicit opt out options

(e.g., KaZaA and Weatherscope). In addition, we wanted to

include programs that bundled multiple applications (e.g., Kazaa)

and a program that claims it does not bundle software or

functionality (i.e., Webshots).

We did not control for brand reputation. In fact, we wanted to

understand how reputation and prior experience influenced user

decision making. For this reason, we also chose programs from

brands that enjoyed a good reputation, such as Google, to those

that have received substantial negative press, such as KaZaA. In

the end, we chose Google Toolbar, Webshots, Weatherscope,

KaZaA and Edonkey as the test applications.

Importantly, while these applications bundle functionality that

could be adverse to users’ privacy and security preferences, we do

not claim nor did we suggest to participants that any of them

contain spyware. The disclosures and consent procedures can be

integral to whether a program is considered spyware or not, both

by end users and by anti-spyware vendors. Therefore, our

research intentionally included software that users would unlikely

consider to be spyware (e.g., Google Toolbar).

4.1.2 Experiment Scenario

In order to motivate our users to make a decision to install or not

install a given program, we created a scenario for users to follow.

We wanted to provide users with a reason to install the programs,

but we also wanted to ensure that they were not obligated to

install any programs. We thus created the following instructions:

Imagine that a friend (or relative) has asked you to help

set up this computer. The computer already has the most

popular office applications installed. Your friend wants

additional functionality and is considering installing other

software.

Here is a quote from your friend: ”Here are some

programs that were recommended to me by my friends.

Since you know more about computers than me, can you

install the ones you think are appropriate?”

If users decided to install a program, they could double click on

the program’s installation icon and strep through the program

installation and configuration. They could decide at any time to

cancel the installation and go on to the next program.

4.1.3 Notice Conditions

We wished to examine whether different types of notices would

affect a user’s decision to install a program. We were also

interested in capturing if users were aware of each type of notice,

and their recall of the notice after installation. We chose three

different types of notices. Below we describe the characteristics

of each notice condition.

Notice Condition 1 - EULA Only

The first notice condition is a control treatment consisting of only

the original EULAs and notices that are included in each program.

This notice condition represents what most users would see when

they install a program downloaded from the internet.

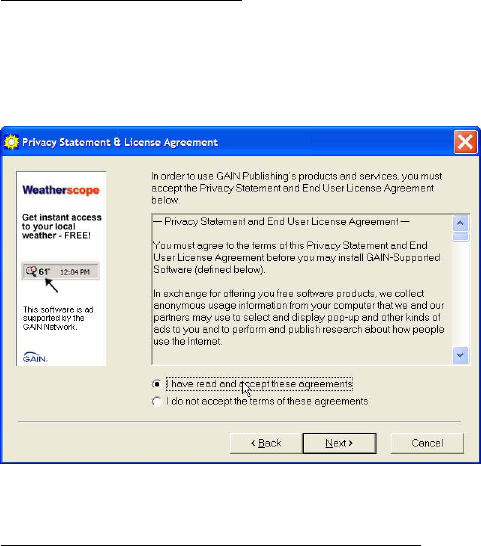

Figure 1 EULA for Webshots

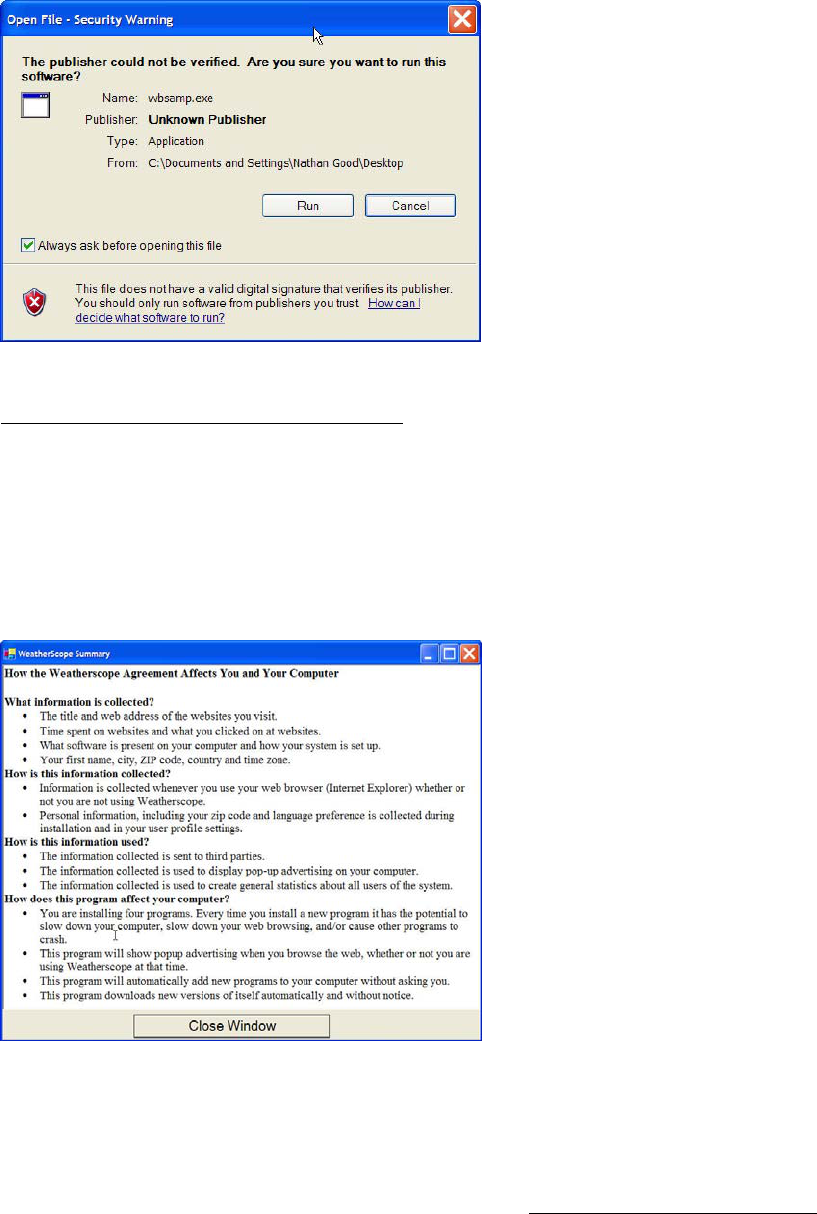

Notice Condition 2 - Microsoft SP2 Short Notice + EULA

In addition to the EULA included in each individual program, the

second notice condition includes a short warning from Microsoft

that is displayed when users begin the installation. This warning

is included with Windows XP Service Pack 2, and is provided for

all programs that are downloaded from the web. If available, the

notification includes a link to the publisher information as well as

links to privacy policy information. The purpose of this notice

condition is to test if a commonplace heightened-notice practice,

active by default, will affect installation behavior.

4

Figure 2 Microsoft Windows XP SP2 Warning

Notice Condition 3 - Customized Short Notice + EULA

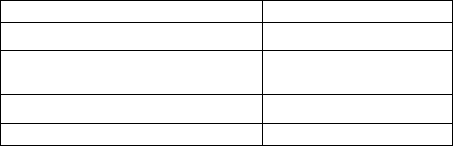

The third notice condition consists of a layered notice: a

customized short notice in addition to the EULA included in each

individual program. In this notice condition, the short Microsoft

warnings shown in notice condition 2 were disabled. Users were

instead presented with a window that provides specific

information about each program (see Figure 3). When users

reached the portion of the installation program that showed the

EULA, this window appeared in the forefront of the EULA

automatically. We describe how we decided on the content and

presentation of these short notices in more detail below.

Figure 3 WeatherScope Customized Short Notice

4.1.4 Creating the Short Notices

As noted above, there exists considerable legal and computer

security literature that deals with short notices. The actual content

that a short notice should contain is slightly different in each

proposal, but they all recommend that the most relevant

information should be presented clearly and concisely. The EU

model suggests that the condensed notice should contain all the

relevant information to ensure people are well-informed about

their rights and choices

10

. The key points of a short notice are that

they should use language and layout that are easy to understand,

and they should include:

- The name of the company

- The purpose of the data processing

- The recipients or categories of recipients of the data

- Whether replies to questions are obligatory or voluntary,

as well as the possible consequences of failure to reply

- The possibility of transfer to third parties

- The right to access, to rectify and oppose

The purpose of our study is neither to create a new standard for

short notices, nor to evaluate the effectiveness of various language

terms. Rather, our goal is to determine if any short notice would

have an effect on a user’s installation decisions. For this reason,

we chose to emphasize the aspects of a EULA that were

consistent with users expressed privacy/security preferences, such

as items describing third party access to information and the

impact on machine performance (slow down, crashing, popups,

etc.). We borrowed heavily from existing recommendations when

appropriate, using a simple layout, bullet points and easy to

understand language. We created a series of five generic

privacy/security questions, which we answered for each program

in the notice. An example short notice is shown in Figure 3:

We derived the content for each short notice by examining the

TOS and EULA for each program, and answered each of the five

questions described above using consistent language across

notices. Our aim was to include information that those skilled in

the art would know or be able to infer about the program by

installing it.

Information about uninstalling programs is also important to

users, however we did not include this in our short descriptions. It

is difficult to articulate how easily a program can be removed, and

we lacked the detailed technical knowledge about each individual

program to determine what is actually removed by uninstalling the

program. However, we thought it would be valuable to capture

user capabilities in detecting and uninstalling software using

common Microsoft Windows tools. Therefore, we included

related questions in a post-installation survey. In future work, we

will look more closely at user behavior in the uninstall process.

4.1.5 Surveys and Post Study Interview

We expected that users may be influenced by a multitude of

individual preferences and strategies when installing software.

For example, some participants might be driven by a positive

prior experience with a program or company, while others may be

primarily influenced by a program’s functionality. To gain

greater insight into the considerations affecting installation

decisions, we interviewed each user after the study. Each

interview was a mix of standardized surveys and in depth open-

ended questions that lasted between 35 and 60 minutes.

5. RESULTS

5.1 Participant Demographics

Our user sample consisted of 31 participants: 14 males and 17

females recruited by a university recruiting service that were

comprised of university undergraduates. All used the Windows

10

Opinion on More Harmonised Information Provisions.

Available at

http://europa.eu.int/comm/internal_market/privacy/docs/wpdocs/2004/w

p100_en.pdf.

5

operating system on their home computer, and 24 of them

maintained their computer at home themselves. 14 participants

had an age of under 20, 16 were aged between 20 and 25. They

spent an average of 26 hours a week on their home computer (std.

dev. of 12), and 2.5 hours a week on work computers (std. dev. of

4).

5.2 Installation Decisions

5.2.1 What factors contributed to participants’

decision to install programs?

One of the goals of performing an ecological study is to observe

user behavior installing programs in a near-natural setting. It

allowed us to ask questions about their motivations and actions.

We observed whether users paid attention to EULAs, and if so,

what particular information they obtained or sought. Other factors

we examined are why participants installed programs, and what

process they followed. We discovered that our participants shared

general concerns about what is installed and the effect it has on

their computer. Participants varied widely in their installation

procedures.

5.2.2 Install Process

Participants’ reasons for installing programs varied. Some

participants only installed applications that they felt comfortable

with. Other participants installed everything with the intention of

checking out unknown programs and uninstalling them later. The

following categories demonstrate some of the main strategies we

observed (we note that we do not consider this to be an exhaustive

list of all possible user motivations or to be representative of the

general population):

Install first, ask questions later: These participants generally

installed all programs at once, with the intention of examining

them in greater detail later. They tended to consider themselves

computer savvy, with the ability to remove or configure programs

after installation to avoid adverse affects to their machine. They

felt sufficiently familiar with the installation process and tended to

click through each screen very quickly.

Once Bitten, Twice Shy: These participants were somewhat

computer savvy, but they were influenced by past negative

experiences. One participant had recently been a victim of a

phishing attack, while another had a program “totally cripple” her

laptop. They have had past computers crash or become

inoperable because of rogue programs or viruses and often lost

data. These users tended to be overly cautious, and they chose to

install applications only if they felt those applications were

absolutely required. They typically skimmed EULAs and

programs’ information for key phrases such as “ads,” “GAIN,” or

“popups” to avoid choices that would potentially be harmful.

Curious, feature-based: These participants were primarily

interested in potentially new and interesting features delivered by

the selection of programs. They would only install an application

if it was popular or offered something that they would want or

need. These users would typically install a program such as

WeatherScope because they thought it was “cool” and “useful.”

Computer-Phobic: These participants were generally wary of

anything that had to do with installing programs or configuring a

computer. They sought assistance from their friends or other

experts when they had problems, and they would generally

request help with any install. One participant mentioned that her

father was a savvy computer user and “passed on paranoia” to her.

They were generally very concerned with any warning that

popped up, and were reluctant to install anything.

5.2.3 Installation Concerns

Our participants shared a range of common concerns about

installing software. They are listed in order of importance in our

sample below:

1) Functionality (>80%) – A large majority of participants

who expressed some form of concern were primarily

interested in the functionality of the application. By

functionality, they mean convenience, lack of other

alternatives, its “cool factor” (direct quote) and its

purpose. Participants were most interested in programs

that are “necessary,” “helpful,” or “convenient, easy to

use” and would add some “aesthetics.”

2) Popups (~60%) – popup advertising was the second

largest concern out of our participants, across all

categories of users. Many users had strong reactions to

them. “I hate them!” was a reaction echoed by several

participants. Many were extremely reluctant to install a

program that had popup advertising or seemed like it

would. One participant stopped an installation after she

saw the word “GAIN,” which reminded her of Gator, a

company that had put advertising on her machine

before.

3) Crashing their machine, computer performance (~30%)

– Some participants were worried that programs would

crash their machine, take up space, or cause their

machine to be unstable. This was especially a concern

with the ‘Once Bitten, Twice Shy’ participants.

4) Installing additional software (~15%) – Participants

were concerned about software that installed additional

programs. “I don’t want a lot of junk on my computer”

remarked one user. “Junk” was classified as additional

programs that ran in the background, that changed

homepages, slowed the machine, caused it to crash

and/or served ads.

5) Monetary cost (~10%) – Some users were concerned

that they may be eventually charged later for software

they installed, even though they did not enter any credit

card information.

6) Sends information (<5%) – Our participants never

directly mentioned privacy concerns as a reason to not

install a program, but several mentioned that they would

be wary of programs that collected personal information

because they thought it would lead to spam or more ads

on their machine. They referred to personally

identifiable information such as email addresses.

5.2.4 What did users install?

We were curious what effect notice had on users installing

programs. As discussed above, we ran three notice conditions on

31 subjects. We observed their behavior and asked them

questions about their actions. A breakdown of subjects is

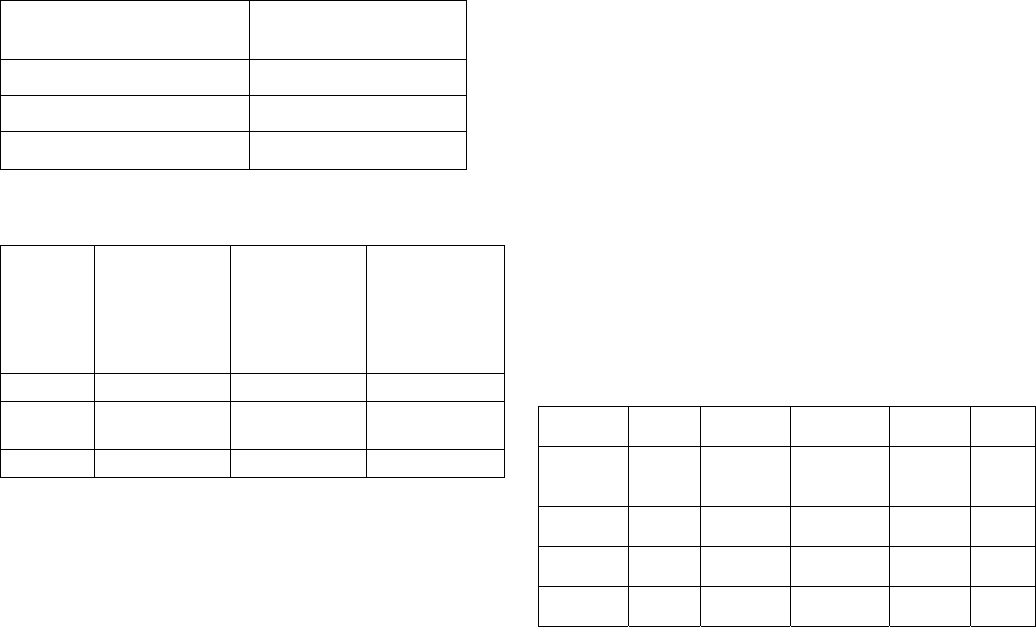

included in

Table 1.

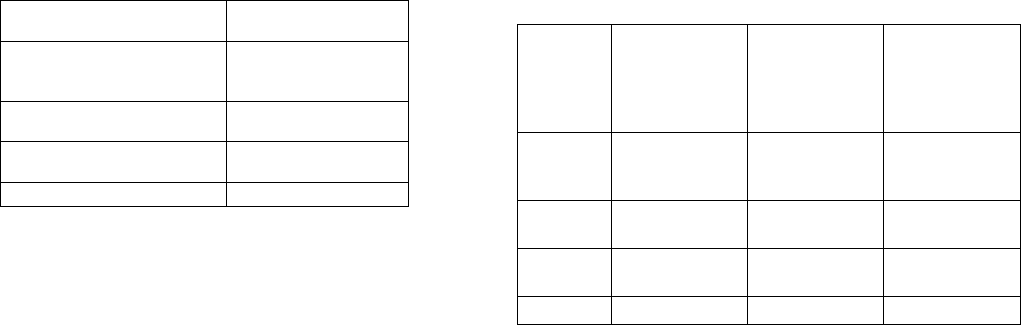

Table 1 Breakdown of subjects by notice condition

Number of Subjects

Control (EULA Only)

10

Generic Microsoft + EULA

10

Short Notice + EULA

11

Total

30

6

Table 2 indicates that additional notice (in the form of the generic

Microsoft warning or the short notice) had only a marginal impact

on the total number of installations (by ~10%, p >.1). However,

the post-interview process showed that participants felt better

informed in the notice condition 3 (short notice). In the following

we describe in more detail their reactions to notice condition 2

(generic Microsoft notice) and notice condition 3 (short notice).

Table 2 Total Installs for per notice condition

Installs by notice

condition

Control (EULA only)

36 (72%)

Generic Microsoft + EULA

31 (62%)

Short Notice + EULA

35 (63%)

Table 3 Number of participants that could remember

additional notices

Notice

condition

Participants

who

remembered

to have seen

an additional

notice

Participants

who

remembered

the content of

the additional

notice

Participants

for whom the

notice affected

their decision

to install

Generic

6 of 10 8 of 10 4 of 10

Short

EULA

11 of 11 10 of 11 7 of 11

Total

17 of 21 18 of 21 11 of 21

5.2.5 Generic Microsoft Notice + EULA

Table 3 reproduces the number of participants that could

remember seeing the generic Microsoft notice (60%), that could

remember some content of the notice (80% with additional

probing) and remember that it had some effect on their decision to

install (40%). Some participants found the generic notices to be

useful; particularly if the generic warning indicated to users that

there was no known publisher. One participant stated “Edonkey

didn’t look good. The notice said ‘unknown publisher’, so I chose

not to install it.” However, none of the participants clicked on the

link that provided more information about the publisher if the

publisher’s identity was known. Several users instinctively

clicked through the notices without even reading them. When

asked if they saw them, they said no, but when prompted with a

blurred version of the notice they said, for example, that they have

seen similar notices in the past. One participant mentioned that “it

asked you whether or not you wanted to download it, [and] gave

the company name, info and licensing agent.”

5.2.6 Short Notice + EULA

Table 3 shows that all participants could remember having seen

the short notice, and that 91% could remember some details of

their content. 64% stated that the short notice influenced their

decision to install the programs. Participants were generally

enthusiastic about the short notices we created. One user wanted

to know where we got it, because he wanted to use it at home.

Others remarked that they “were amazing,” and that they would

“love to see this, it would be really awesome!” When further

prompted for reasons to use this kind of short notices, this

participant remarked “I personally wonder how many people just

install stuff [without thinking], wouldn’t be surprised if it was the

majority.” Others stated that they used the information in the

short notices to compare programs and assist their decision. One

user said “the pop-up windows said the programs were no good,

[and I] might not have known without them”.

Most participants were able to recall parts of the content of the

short notices as well. They mostly recalled the issues that they

were most concerned about (e.g., pop-ups and system

performance). Several users were concerned about information

transfers to third-parties, and some mentioned that the information

in the short notices “surprised them.”

Despite the positive reactions, some users simply ignored them as

well. Despite stating in the post-interview that they would like

“clear and concise” information, they made comments such as, “It

is hard to say if I would read them [short EULAs] even if you

flashed IMPORTANT at the top. After the third or fourth one I

wouldn’t read and it would be easy to skip.”

5.2.7 What programs were installed most?

For each notice condition we were also interested in what

programs users installed. We saw that the Google Toolbar was

the most often installed among all sets, whereas Weatherscope

ranked last. Main reasons for this effect were brand recognition

and prior experience. Users mentioned, for example, that Google

“was a trusted brand name” and that they “thought Google toolbar

did a good job at blocking popups.”

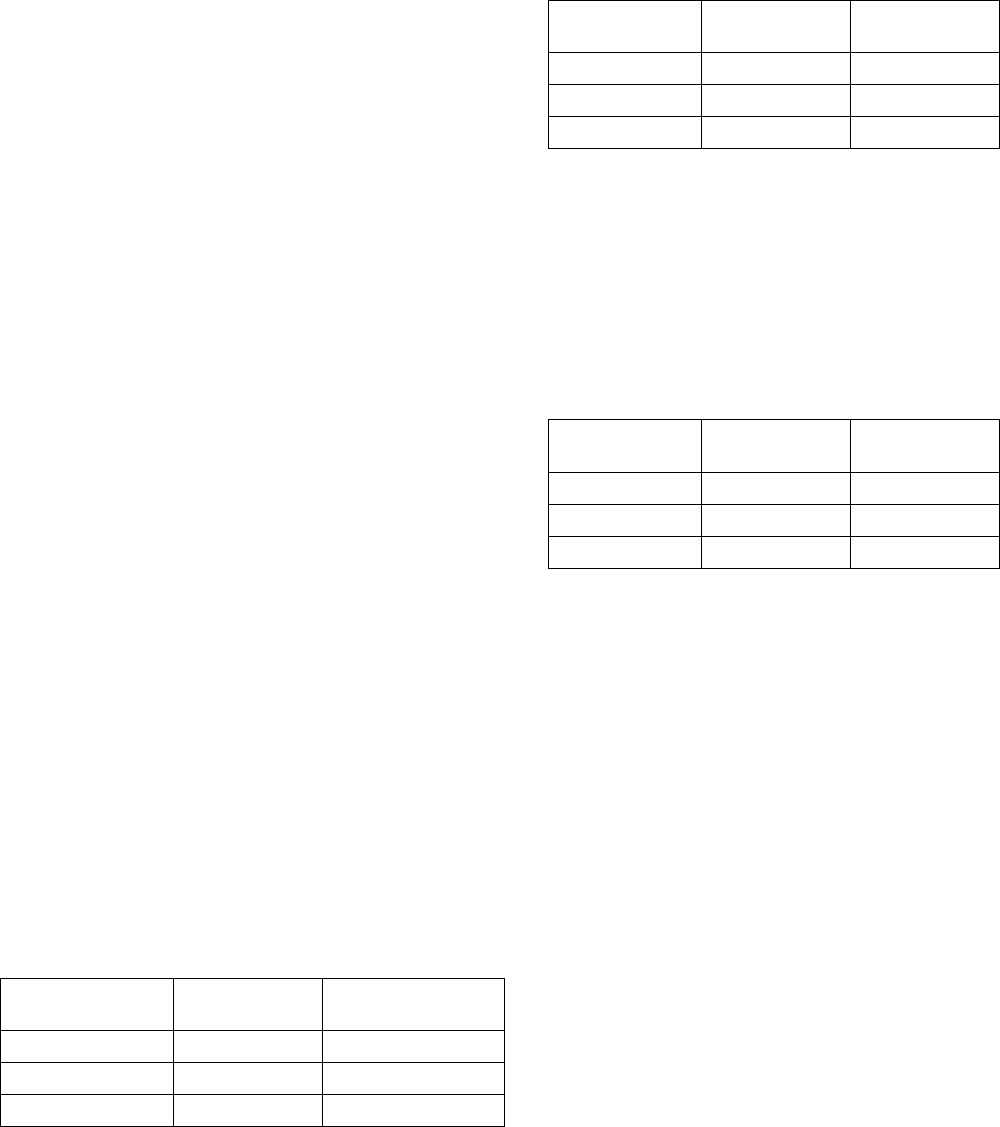

Table 4 Installation frequency by notice condition

Notice

condition

Kazaa Edonkey Webshots Weather

Scope

Google

Control

(EULA

Only)

3

(22%)

9

(89%)

9

(89%)

6

(55%)

9

(89%)

Generic +

EULA

6

(60%)

3

(30%)

7

(70%)

6

(60%)

9

(90%)

Short +

EULA

6

(55%)

5

(45%)

10

(91%)

3

(27%)

11

(100)

Total

14

(47%)

16

(53%)

25

(83%)

14

(47%)

28

(93%)

Weatherscope was rarely installed because it reminded users of a

similar program called “Weatherbug,” which was universally

disliked because “it had too many popups” and it “crashed my

machine.” Users also mentioned that the benefits that are

associated with programs such as Weatherscope or Weatherbug

did not outweigh the higher cost of dealing with popup

advertisements. A user remarked “you can go to weather.com if

you really want to check the weather, and then you don’t have to

deal with any popups.” Details are reported in Table 4.

5.2.8 FileSharing as a "must-have” application

We discovered that among our user population and demographic,

filesharing was a “must-have” application. Although users

typically installed only one filesharing application, 23 of the 31

users felt that they should have at least one filesharing application.

Users mentioned that filesharing applications were “very useful”

and something that “everyone should have.” However, in

choosing the filesharing application to install, users frequently

tried to determine which application would be less intrusive on

their machine. Some users used the short notices to compare

filesharing applications by what they said, while others were

influenced by the fact that one was “trusted” (as indicated in the

7

generic Microsoft warnings for KaZaa) and the other was

”unknown” (and therefore less trustworthy). Overall, more users

installed eDonkey over KaZaA not because they knew about it,

but because many of the users had negative experiences with

KaZaA and would not install it again. User complained that “it

crashed my machine”, “I had to reinstall everything again,” and

that “it had too many popups.”

Table 5 Users who didn't install a Filesharing Application

Notice condition Didn’t install one

Filesharing program

Control

(EULA Only)

1

Generic + EULA

2

Short notice + EULA

4

Total

7

5.2.9 Vague short notices can also lead users to

assume false security

An interesting result discovered in the installation process was the

higher number of installations for KaZaA in the short notice case

as opposed to the control case (see Table 4). In talking with

participants about their choice to install or not, we discovered that

they were more likely to install KaZaA instead of Edonkey

because it “didn’t seem as bad.” This case was especially

pronounced in the case of the short notices because users typically

wanted to install one or the other, and used the information in

them to determine which one to install. This was interesting

because Edonkey actually disclosed more, and gave users the

option to opt-out of certain instances, whereas KaZaA did not

have that option. However, in creating our short notices, we had

to follow what was stated in the EULA, which for KaZaA was

vaguer than Edonkey. In this case, providing vague information

created an impression of increased security.

5.3 Knowledge of Contract Terms

5.3.1 Did Users Look at EULAs?

Participants generally ignored EULAs. Drive-by installers were

especially adept at clicking through installation screens extremely

quickly. Some users went through this process so quickly that

they did not even remember clicking through the short notices and

the Microsoft warnings as they popped up. One drive-by

participant remarked that “[t]he process is so standard, there is

nothing to influence [your decision] to install or not. I just use all

the default options and configure it later if I am going to keep it.”

5.3.2 EULAs and TOS as legally binding documents

Our participants were generally ambivalent towards the EULAs

and TOS in the software they installed. Table 6 shows that while

almost all participants were aware that they were agreeing to a set

of terms by installing the software (30 of 31), they were generally

unable to recall the content of the agreement (8 of 31), and it

rarely influenced their decision to install a program (6 of 31). The

participants who did recall contents of the EULA remarked that it

was generally about information that referred to the software

product itself, such as “copyright notices”, “company policies”, or

“reverse engineering the product or using it for unintended

purposes.” Almost none of the participants, including the more

computer savvy ‘Install first, ask questions later’ users, had any

idea that the content of the EULAs and TOS actually discussed

applications that would be installed, data that would be collected,

and companies that would access their data. There seems to be a

strong disconnect between user expectations of EULA content and

actual EULA content. One user summed up this confusion by

stating “They should have notices to show what they are really

installing on the computer. They trick you [into] thinking it is just

a license agreement, [you] hit OK, and then you get an advertising

bar or a lot of junk!”

Table 6 Noticing EULAs

Notice

condition

Participants

aware that the

Software

EULA was a

contract

Participants

who had an

idea of what

the agreement

contained

Participants

for whom the

EULA affected

their decision

to install

Control

(EULA

only)

10 of 10 2 of 10 3 of 10

Generic

+ EULA

10 of 10 5 of 10 2 of 10

Short

+ EULA

10 of 11 1 of 11 1 of 11

Total

30 of 31 8 of 31 6 of 31

5.3.3 EULAs and TOS appearance

A great deal of anecdotal evidence and research suggests that the

current design of EULAs and TOS makes them inaccessible to

users. Our participants confirmed this verbally as well. They

stated that the “font was too small,” they were “too long” and

“full of legal mumbo-jumbo.” A few users had read parts of

EULAs carefully on one occasion, but eventually gave up on

reading them due to lack of brevity. Our participants had several

suggestions about how license presentations can be improved, but

most notably they wanted them “shorter, easier to read and in very

accessible language.” One participant stated that she would like

to see something “that would tell you exactly what you want to

know. [It would] provide a summary first, bold whatever is

important, bold what is in the software, who is using it, and say if

it is safe to download.”

5.4 Regretting Installation Decisions

We were interested in learning if users would change their mind

about programs once they were informed about the actual contents

of the package they installed. We showed the short notices to all

users at the end of the survey to determine whether users read

them earlier (this applies to the short notice condition only) and if

users thought the notices would have influenced their installation

decisions (applies to all notice conditions). Users were asked to

read each of the short notices carefully, and to decide whether

they would like to reverse their earlier decision to install or not to

install. Such regret or disappointment materializes if an earlier

decision appears to be flawed in retrospect, and/or when the

obtained result does not match prior expectations [11].

We found that regret was highest with Weatherscope and the

filesharing programs. In addition, users were generally happier

with their decision not to install these programs after reading our

short EULAs. User regret generally stemmed from popups,

performance issues, and the potential disclosure of private

information to third parties. Some users were upset, stating “I

didn’t install that!”, while others were surprised at the extent of

information collection they had agreed to by installing and using

certain programs. Users remarked that they would remove

8

programs that had popups “If I had known this had popups I

wouldn’t have installed it.”

5.4.1 Regret With Filesharing Applications

Despite the regret that some users had for filesharing programs,

many indicated that they would still install them. One user who

expressed regret at her decision to install eDonkey said “if all free

music programs do this, and I can’t find anything better then I’m

going to install it. For a free photo program it might not be worth

it, but for free music it is.” Another user added “I really don’t like

that it adds other software, but I would still keep it because

filesharing is worth it.”

5.4.2 Regret with Trusted Sources

In the case of Google Toolbar, the program with the greatest

brand recognition among our users, the reasons for uninstalling

were related to performance and space issues, rather than concerns

with privacy or computer security issues. One user indicated that

he “didn’t want another thing in their browser window” and that

they liked to keep the minimum amount of programs running at

any given time.

5.4.3 Regret across notice conditions

We studied the degree of participant regret over an installation

decision in relation to each notice condition. We expected that

users would experience less regret when they were better

informed (i.e., additionally being provided with a short notice or a

generic Microsoft notice). In fact, participants verbally indicated

that especially the short notices had a substantial effect on their

decision to install or not. Compared to the control notice

condition, participants experienced regret about 15% less often

than in the notice conditions with short notices and generic

Microsoft warnings (however, this effect is not significant in an

ANOVA (p<.05)).

The set of programs included in our study included applications

that the community of our participants had deemed generally

“useful,” that is they had a high install rate and low regret rate and

were generally positively commented upon (e.g., Google). The

study also included other programs that our community deemed

“not useful,” that is they had a low install rate and a higher regret

rate. We divided the applications into two groups, “useful” and

“not useful,” and examined user regret across each notice

condition. The “good” applications consisted of Google and

Webshots, and the “bad” applications consisted of Edonkey and

Weatherscope. Google toolbar was the highest trusted

application, with 93% of users installing it, and 83% of the people

deciding to keep it after reading the short notice in the post-study

interview. Weatherscope was on the other end of the spectrum,

with just 47% of the recipients choosing to install it overall and

only 1 user out of 31 choosing to keep it.

Table 7 Installation Regret per Notice condition (Number of

installations regretted)

Regretted

installing it

Regretted not

installing

Control

19 (52%) 2

Short notice

13 (37%) 2

Generic notice

11 (35%) 0

We found (see Table 8) that users in the two notice conditions had

lower levels of regret compared to the control condition for both:

“useful” and “not useful” applications. Results between these

notice conditions were not statistically significant, but supported

by participant comments in the post-study interview.

Table 8 Regret for “useful” versus “not useful” applications

Regretted install

“useful”

Regretted install

“not useful”

Control

6 13

Short notice

6 5

Generic notice

1 9

We also studied whether the different notice conditions influenced

users by preventing them from installing applications that were

deemed “not useful” by the community. Table 9 shows that the

number of “not useful” installs is similar for both the short and

generic notices, and 6-7 programs less compared to the control

case. Participants also installed more programs that the

community considered “useful” in the short notice case, but fewer

programs in the generic case. This may be due to the ‘warning’

rather than ‘informing’ character of the generic Microsoft notice

that may have scared participants away.

Table 9 Installation of “useful” versus “not useful”

applications

Installed

“useful”

Installed “not

useful”

Control

18 15

Short notice

21 8

Generic notice

16 9

5.5 Limitations of Our Study

Our study was limited to a small sample of students. Participants

were very young, mostly female and relatively computer savvy.

Therefore, our study is not an accurate representation of the larger

population. We further expect that a different selection of

programs could have influenced our results. However, every

possible alternative choice of program would have a certain brand

recognition and emotional loading associated with it (e.g., higher

or lower likelihood that users had a positive prior experience).

Our experimental protocol was aimed to make the individual

observations of participants as comparable as possible. Our intent

was to test assumptions about notice and spyware, and use the

results to help inform future studies.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Our study indicates that while notice is important, notice alone

may not have a strong effect on users’ decision to install an

application. We discovered that users generally knew they were

agreeing to a contract when clicking through a EULA screen.

However, we found that users have limited understanding of

EULA content and little desire to read lengthy notices. When

users were informed of the actual contents of the EULAs to which

they agreed, we found that users often regretted their installation

decisions.

Although short notices did improve understanding of the

consequences of the installation, they did not have a statistically

significant effect on installation. While more tests and subjects

will help to explore these results, we feel that our data show that

improved notices alone may not be enough to inform users and

match their actual privacy preferences to the software they install.

9

In addition, we found that functionality is the most important part

of an application for many users, although it is not the only factor

they use to make a decision. Regardless of the bundled content,

users will often install the application if they believe the utility is

high enough.

It may be tempting to interpret our results to claim that users do

not care about privacy, especially when the utility of a software

application is high for a particular user. However, we discovered

that privacy and security become important factors when choosing

between two applications with similar functionality. Given two

similar programs (e.g., KaZaA and Edonkey), consumers will

choose the one they believe to be less invasive and more stable.

We also found that providing vague information in EULAs and

short notices can create an unwarranted impression of increased

security. This places increased importance on the accuracy and

presentation of the information that users consult to make their

installation decisions. In these cases, it may be helpful to have a

standardized format for assessing the possible options and trade-

offs between applications.

7. FUTURE WORK

In future work, we will experiment with other mechanisms to

inform and provide transparency to users. We plan to perform a

more controlled experiment on notice, for example, by removing

the influence of brand recognition. Our ecological study provides

a foundation on which to base such complementary research. One

further approach is to investigate the use of trusted third parties to

provide notice information to consumers. Another area of

research is to explore the trade-offs between software features and

privacy preferences.

8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank our study participants, UC Berkeley’s

Haas School of Business X-lab for use of their facilities, the

School of Information Management and Systems for providing

equipment and support, and the Samuelson Law, Technology, and

Public Policy Clinic for funding our research. We thank Nicolas

Christin and Jack Lerner for many helpful suggestions.

9. REFERENCES

[1] Abrams, M., Eisenhauer, M. and Sotto, L. (2004) “Response to the

FTC request for public comments in the Advance Notice of

Proposed Rulemaking on Alternative Forms of Privacy Notices

under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act”, Center for Information Policy

Leadership, March 2004. Available at:

http://www.hunton.com/files/tbl_s47Details/FileUpload265/685/CIP

L_Notices_ANPR_Comments_3.29.04.pdf

[2] Ackerman, M., and Cranor, L. (1999) “Privacy Critics: UI

components to safeguard users' privacy,” Proceedings of CHI '99,

extended abstracts.

[3] Acquisti, A. and Grossklags, J. (2005) Privacy and Rationality in

Individual Decision Making, IEEE Security and Privacy, IEEE

Computer Society, Vol. 3, No. 1, January/February 2005, pp. 26-33.

[4] Acquisti, A. and Grossklags, J. (2005) “Uncertainty, Ambiguity and

Privacy,” Fourth Annual Workshop Economics and Information

Security (WEIS 2005), MA, 2-3 June, 2005.

[5] AOL/NSCA Online Safety Study, America Online and National

Cyber Security Alliance, October 2004. Available at:

http://www.staysafeonline.info/news/safety_study_v04.pdf

[6] Bartram, L., Ware, C., Calvert, T., (2003) “Moticons: detection,

distraction and task”, International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies 58: 515-545, Issue 5 (May 2003).

[7] Berthold, O., Köhntopp, M. (2000) “Identity Management based on

P3P”, in: Federrath, H. “Designing Privacy Enhancing

Technologies”, Proceedings of the Workshop on Design Issues in

Anonymity and Unobservability, Springer, pp. 141-160.

[8] Cranor, L., Reagle, J., and Ackerman, M. (1999) "Beyond Concern:

Understanding Net Users' Attitudes About Online Privacy”, AT&T

Labs-Research, April, 1999.

[9] Dourish, P. and Redmiles, D. (2002) "An approach to usable security

based on event monitoring and visualization,” Proceedings of the

2002 workshop on New security paradigms, September 2002.

[10] Earthlink (2005) “Results complied from Webroot's and EarthLink's

Spy Audit programs”. Available at:

http://www.earthlink.net/spyaudit/press/ (last accessed February 25,

2005)

[11] Gilbert, D., Morewedge, C., Risen, J. and Wilson, T. (2004)

“Looking Forward to Looking Backward: The Misprediction of

Regret”, Psychological Science, Vol. 15, No. 5, pp. 346-350.

[12] Good, N.S., Krekelberg, A.J. (2003) “Usability and Privacy: A study

of Kazaa P2P file-sharing”, in: Proceedings of CHI 2003.

[13] HIPAA Highlights Privacy Notice, Press Release, Center for

Information Policy Leadership, Hunton and Williams

http://www.hunton.com/news/news.aspx?nws_pg=7&gen_H4ID=10

102

(last accessed May 24, 2005)

[14] Bettman, J.R., Payne, J.W. and Staelin, R. (1986) “Cognitive

Considerations in Designing Effective Labels for Presenting Risk

Information,” J. Pub. Pol’y & Marketing, 5, pp. 1-28.

[15] Jensen, C. and Potts, C. (2004) “Privacy policies as decision-making

tools: an evaluation of online privacy notices”, in: Proceedings of

ACM CHI 2004, Vienna, Austria, pages 471-478.

[16] PC Pitstop (2005) “It pays to read EULAs.” Available at

http://www.pcpitstop.com/spycheck/eula.asp (last accessed May 24,

2005)

[17] Platform for Privacy Preferences Project (P3P).

http://www.w3.org/P3P/

[18] Spiekermann, S., Grossklags, J. and Berendt, B. (2001) “E-privacy

in 2nd generation E-Commerce: privacy preferences versus actual

behavior”, in: Proceedings of the Third ACM Conference on

Electronic Commerce, Association for Computing Machinery (ACM

EC'01), Tampa, Florida, US, pp. 38-47.

[19] Trafton, J. G., Altmann, E. M., Brock, D. P., Mintz, F. E. (2003).

“Preparing to resume an interrupted task: effects of prospective goal

encoding and retrospective rehearsal”, International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies 58: 583-603.

[20] Van Dantzich, M., Robbins, D., Horvitz, E. and Czerwinski, M.

(2002) “Scope: Providing awareness of multiple notifications at a

glance”, in: Proceedings of Advanced Visual Interfaces 2002,

Trento, Italy.

[21] Wired. “Spyware on My Machine? So

What?”:http://www.wired.com/news/technology/0,1282,65906,0

0.html

10