i

QGN 16

Guidance Note for Fatigue Risk

Management

Coal Mining Safety and Health Act 1999

Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health Act 1999

[Type here]

© State of Queensland, Department of Natural Resources and Mines, 2013.

The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The

copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence.

Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from Department of Natural Resources and

Mines, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms.

You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland, Department of Natural

Resources and Mines as the source of the publication.

For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en

[Type here]

Foreword from the Commissioner for Mine Safety and Health

Fatigue has long been recognised as a hazard in the mining industry. There has been a

considerable body of research and development work done in this area in recent years. The

mining industry in Queensland is aware of the hazards associated with fatigue and is

proactively seeking solutions and control strategies.

This document, “Guidance Note for Fatigue Risk Management”, outlines the various

considerations to effectively manage fatigue. It provides mine operators (coal mine

operators, mine and quarry operators) and mine workers (coal mine workers, mine and

quarry workers) with a comprehensive overview of the factors that contribute to workplace

fatigue and how they can be controlled. Fatigue is no longer viewed as an issue only for the

individual; rather it is a multi-facetted hazard that requires a multi-facetted approach to

manage the risk.

This guidance note supersedes the 2001 Guidance Note for Management of Safety and

Health Risks associated with Hours of Work Arrangements at Mining Operations produced

by the then Department of Natural Resources and Mines.

The knowledge and application of evidence based fatigue risk management practices has

increased dramatically since 2001, and this guide incorporates information, research and

good practice from a number of sources. It provides a human factors approach

acknowledging the inter-relationship between people, workplace and management factors

influencing fatigue in the workplace.

This guide addresses the fatigue-related factors in all elements of the system. The goal is to

reduce the likelihood of fatigue-related incidents or errors.

This document was prepared to assist mine and quarry operators and workers in taking the

necessary measures to control the risks associated with fatigue.

Stewart Bell

Commissioner for Mine Safety and Health

The interaction of

human factors

[Type here]

Acknowledgements

This guide is based on the Industry and Investment New South Wales (NSW) document,

Fatigue management plan: a practical guide to developing and implementing a fatigue

management plan for the NSW mining and extractives industry, which has been developed

and endorsed by the NSW Mine Safety Advisory Council. The NSW publication also used

content from the joint WorkSafe Victoria and WorkCover New South Wales guidance

(Fatigue - prevention in the workplace). The Department of Natural Resources and Mines

(DNRM) acknowledge the assistance of Industry and Investment NSW in allowing the use of

the document in developing this guide.

In the development of this guide a number of other fatigue guidance publications were

consulted as well as research on sleep, fatigue, sleep disorders and other related issues.

This guide received input from and review by the Queensland Mine Safety and Health

Advisory Committee (QMSHAC) and Queensland Coal Mine Safety and Health Advisory

Committee via the joint Fatigue Working Party. Organisations represented on the QMSHAC

Fatigue Working Party are: the Australian Workers Union; Construction, Forestry, Mining and

Energy Union (Mining and Energy Division); Queensland Mine Safety Advisory Committees;

DNRM Safety and Health and Queensland Resources Council (QRC).

[Type here]

Guidance Note – QGN 16

Guide to Fatigue Risk Management

This Guidance Note has been issued by the Mines Inspectorate of the Department of Natural

Resources and Mines (DNRM). It is not a Guideline as defined in the Mining and Quarrying

Safety and Health Act 1999 (MQSH Act) or a Recognised Standard as defined in the Coal

Mining Safety and Health Act 1999 (CMSH Act). In some circumstances, compliance with

this Guidance Note may not be sufficient to ensure compliance with the requirements in the

legislation. Guidance notes may be updated from time to time. To ensure you have the latest

version, check the DNRM website: https://www.business.qld.gov.au/industry/mining/safety-

health or contact your local Inspector of Mines.

North Region

PO Box 1752

Townsville Qld 4810

Ph (07) 4447 9248

Fax (07) 4447 9280

North Region

PO Box 334

Mount Isa Qld 4825

Ph (07) 4747 2158

Fax (07) 4743 7165

North Region

PO Box 210

Atherton Qld 4883

Ph (07) 4095 7023

Fax (07) 4095 7044

South Region

PO Box 1475

Coorparoo Qld 4151

Ph (07) 3330 4272

Fax (07) 3405 5345

Central Region

PO Box 3679, Redhill

Rockhampton Qld 4701

Ph (07) 4936 0198

Fax (07) 4936 4805

Central Region

PO Box 1801

Mackay Qld 4740

Ph (07) 4999 8511

Fax (07) 4999 8519

[Type here]

Contents

Acknowledgements i

Contents iii

Purpose of this document 1

Glossary 2

Preface 5

Obligations under Queensland legislative and regulatory requirements 5

Obligations for persons 5

Obligations of holders, operators and SSEs 5

Obligations to ensure an acceptable level of risk is achieved 6

Obligations for consultation with workers 7

Obligations for planning, organisation, leadership and control 7

Summary 8

What is fatigue and why is it a problem? (Chapter 1) 8

Who needs a fatigue risk management plan? (Chapter 2) 8

Developing and implementing a plan to manage the risk of fatigue (Chapter 2) 8

Consultation (Chapter 3) 8

Role clarity (Chapter 4) 8

Risk management (Chapter 5) 9

Documentation (Chapter 6) 9

Implementation (Chapter 7) 9

Evaluation (Chapter 8) 9

1. Introduction 10

1.1 Background 10

2. Fatigue risk management plan: development and implementation overview 12

2.1 Introduction 12

2.2 Approach 12

2.3 Resources needed for an effective fatigue risk management plan 14

3. Consultation 15

3.1 Introduction 15

4. Roles and responsibilities 16

4.1 Operator/SSE 16

4.2 Mine workers (or coal mine workers) 16

4.3 Who should be involved in implementation of fatigue prevention and management 16

4.4 Approach 17

5. Fatigue risk management 19

5.1 Introduction 19

5.2 Hazard identification: identifying factors that may contribute to fatigue 20

5.3 Risk assessment 22

5.4 Risk control 31

[Type here]

Process for using the risk factor and control tables (Tables 1-4) 33

5.5 Evaluation 45

6. Fatigue risk management plan documentation 46

7. Fatigue risk management plan implementation 47

7.1 Introduction 47

7.2 Timeframes 47

7.3 Training 47

7.4 Communication 48

7.5 Responsibilities 48

7.6 Supervision 48

7.7 Reporting 48

8. Fatigue risk management plan: monitoring and evaluation 49

Appendix 1: Suggested components of worker (and supervisor) fatigue risk management

training 50

Appendix 2: Tips for individuals on avoiding fatigue 51

Appendix 3: Accessing further resources and references 52

Appendix 4: Principles for risk management scoping and review to assist with

planning the fatigue risk assessment 55

Appendix 5: Key points for journey management or commute management plan 57

List of tables

Table 1 Direct risk factors 36

Table 2 Contributing risk factors 40

Table 3 Contributing risk factors: Work design and task specific factors 42

Table 4 Contributing risk factors: Individual and site specific factors 44

List of figures

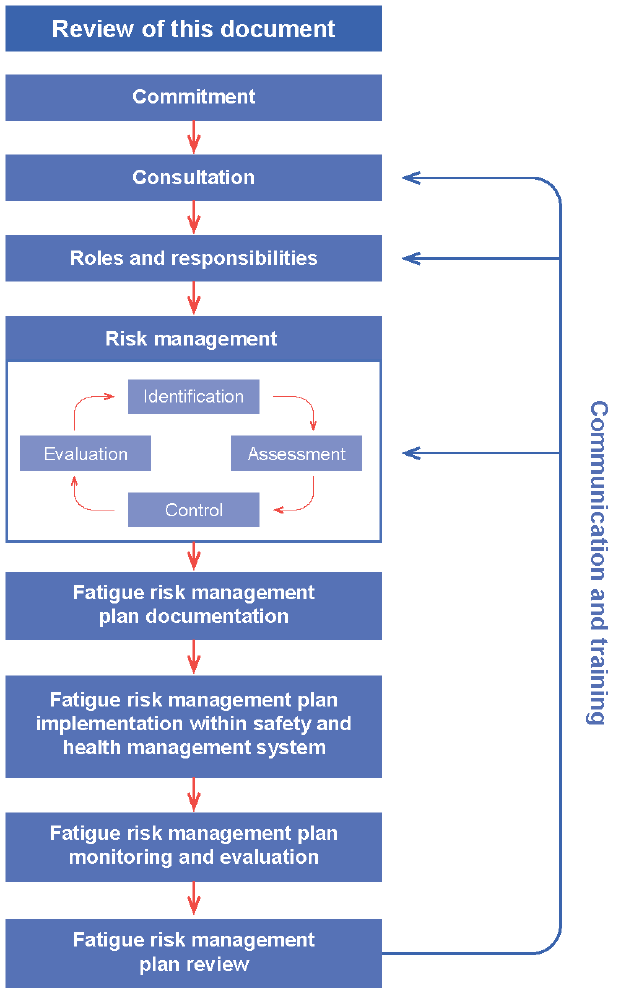

Figure 1 Fatigue risk management plan: development and implementation overview 13

1

Purpose of this document

Guidance on

how to

systematically

manage fatigue

risks

The purpose of this guide is to provide guidance to mining (and coal

mining) operations on how to systematically manage fatigue risks in the

workplace so that the obligation holders comply with the legislative

framework. The guide will help sites develop and implement a fatigue

risk management plan which will contain strategies to effectively control

the risks of fatigue. It sets out a risk management approach based on

consultation with the workforce. The approach requires that mine

(including coal mine) sites:

identify the hazards of fatigue

assess the risks of fatigue using available scientific evidence and

current practice*

implement effective risk control measures

monitor and review regularly the effectiveness of the controls.

Plans must

cover fatigue

risk factors, and

fatigue

contributors as

well as site-

specific needs

The guide is not prescriptive, which means that individual operators and

sites can develop a plan that is specific to their needs. However, all

plans should address each of the main areas identified in this document.

Some smaller sites and quarries may determine that they do not have

the fatigue risk factors that apply to many operations that operate 24

hours. They may find that their planning for fatigue will include a risk

assessment indicating that they have a low risk of fatigue, rather than

developing a plan. The management of fatigue should also be

incorporated in the overall safety and health management system.

* Specific requirements for risk assessment for personal fatigue apply under the Coal Mining

Safety and Health Regulation 2001(CMSH Regulation), s.42 and s.10

2

Glossary

Term

Description

Active work

Total time spent at work including overtime. This does not include

time travelling to or from the work site or rest breaks during shifts.

BIBO

BIBO (bus in/bus out) can be used to describe sites where

workers are bussed to and from site on a daily basis. This does

not necessarily mean that a residential camp is provided – it may

be to and from a township.

Commute

Commute is the term given to the journey for a worker to and

from their permanent home, or in some cases, the site

accommodation to the site. It may involve air travel, driving,

company provided bus, car pooling or other means of transport.

The commute can involve both a daily commute to the mine site

(or coal mine site) and, in some cases, a commute to the

worker’s permanent home at the beginning and end of a work

cycle or roster.

Commute management

plan or journey

management plan

The commute (or journey) to and from the mine site can involve

significant distances of driving, bussing (or flying) for some

workers. This can add a number of hours to the period that

workers will be awake (see wakefulness). It is important for sites

to consider factors such as number of hours driving to and from

site on a daily basis, distances travelled, and/or likely number of

hours driving before and after rosters. Sites should also have a

change management process in place for workers to notify the

site designate for changes to their journey plan. This information

forms the commute management or journey management plan

for workers.

Consultation

Consultation with workers is discussion between the site senior

executive or supervisors and affected workers about a matter

with the aim of reaching agreement about the matter. Further

requirements for consultation are specified in legislation and in

this guide.

DIDO

DIDO (drive in/drive out) is the term for sites where workers travel

to site by road, without air travel being provided for access to the

site for all workers. There will still be some workers who fly in to

the nearest airport and drive to (or are driven to) site.

Extended working

hours

Generally, working beyond eight hours is considered to be

extended working hours in other industries and guidance. In

mining, working hours in excess of established rostered hours,

including overtime would be considered extended working hours.

3

Fatigue

Fatigue can be defined as a state of impairment that can include

physical and/or mental elements, associated with lower alertness

and reduced performance. There are a number of contributing

factors to fatigue, but they usually relate to lack of sleep quantity

or quality, extending the time someone is awake (see

wakefulness and extended wakefulness), or other work related or

individual factors.

Fatigue due to loss of sleep quality or quantity can be

experienced after a short period of exposure to sleep loss (acute

fatigue) or over a longer period of time where sleep loss has

accumulated (cumulative fatigue).

FIFO

FIFO (fly in/fly out) is the term given to mining operations that

have accommodation provided, and have workers flown in.

FFW

Fitness for work as used in the Coal Mining Safety and Health

Regulation 2001 (CMSH Regulation), and Mining and Quarrying

Safety and Health Regulation 2001(MQSH Regulation).

Hazard

Hazard (as defined in the CMSH Act, s.19 and MQSH Act, s.20)

means a thing or a situation with potential to cause injury or

illness to a person.

Note: The above definition is not an exclusive description, and

sites can include alternate definitions, for example “hazard

means a thing or a situation with potential to cause harm,

damage, injury or illness to a person.”

Operator/site

Any person or organisation responsible for the employment of

one or more workers on-site. Site includes both coal mine site

and mine site under Queensland mining legislation.

Risk

Risk (as defined in the CMSH Act, s.18 and MQSH Act, s.19)

means the risk of injury or illness to a person arising out of a

hazard. Risk is measured in terms of consequences and

likelihood.

Rostered hours

The hours a worker is rostered to work.

Safety critical task for

fatigue-related issues

or incidents

Although fatigue will have a potential effect on every worker on-

site, the consequences of fatigue will vary depending on the task

being performed. In Queensland mining, the following is the

preferred definition of safety critical tasks for fatigue or ill health.

“Those tasks undertaken by workers whose

action or inaction due to ill health or fatigue, may

lead directly or indirectly to a serious incident

affecting the health and safety of a number of

other persons.”

Sites may also choose to review tasks and identify those workers

who are continuously performing safety critical tasks.

Shift

The hours between the start and finish of established rostered

hours.

Site Safety and Health

Representatives

(SSHR) for mines and

coal mines

A worker elected or selected (under the MQSH Act, Part 7) or a

coal mine worker elected (under the CMSH Act, Part 7) to

represent workers at a mine or coal mine.

4

1

Dawson and Reid (1997) Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature, 388: 235.

Site Senior Executive

(SSE) coal and

metalliferous

As per s.25 of the CMSH Act, the site senior executive for a coal

mine is the most senior officer employed by the coal mine

operator for the coal mine who—

(a) is located at or near the coal mine; and

(b) has responsibility for the coal mine.

or

As per s.22 of the MQSH Act, the site senior executive for a mine

is the most senior officer employed by the operator for the mine

who—

(a) is located at or near the mine; and

(b) has responsibility for the mine.

Time not working

Time outside of working hours. Does not include time travelling to

or from the work site.

Wakefulness and

extended wakefulness

Wakefulness is the term for the period, in hours, of being awake

from the previous block of sleep. Extended wakefulness is the

extended period of being awake that can increase the body’s

desire to sleep, known as homeostatic sleep drive. There is some

variability between individuals in the amount of time awake that

begins to affect performance, but research

1

suggests that after

approximately 16-17 hours of being awake, depending on time of

day, performance starts to decline.

Work cycles / rosters

The working period scheduled between any significant break

away from work.

Work week

This is the number of actual working hours worked by workers or

contractors in any seven day period and is not an ‘averaged’

figure over a monthly roster.

Worker (including mine

worker and coal mine

worker)

Any person who works on the mine (or coal mine) site,

regardless of their employer. This includes contractors. In this

document the term ‘worker’ applies to mine workers and coal

mine unless specific to the legislative context.

5

Preface

Obligations under Queensland legislative and regulatory

requirements

Relevant laws

oblige fatigue to

be eliminated or

controlled

Obligations exist under the Coal Mining Safety and Health Act 1999

(CMSH Act), and the Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health Act 1999

(MQSH Act) to control fatigue risks to as low as reasonably achievable.

The obligations and legislation provided in this guidance note are not

exhaustive, and all obligation holders need to refer to the CMSH Act or

MQSH Act and the Coal Mining Safety and Health Regulation 2001

(CMSH Regulation) or Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health

Regulation 2001 (MQSH Regulation) for the most recent and relevant

legislation that may apply. Legislation can be found at:

http://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/Acts_SLs/Acts_SL.htm

Obligations for persons

Obligations

under

Queensland

mining and coal

mining

legislation for

fatigue risk

management

apply to the

following

holder

operator

site senior executive

appointees in the site management structure

contractor

an erector or installer of plant at a coal mine

a person who supplies a service at a coal mine

supervisor

mine worker (or coal mine worker)

service supplier

persons generally.

Obligations of holders, operators and SSEs

Operators,

SSEs must

apply

systematic risk

management to

achieve an

acceptable level

of risk

ensure the safety and health of mine workers (including coal mine

workers) and visitors to the workplace with regard to fatigue

have a health and safety management system or plan that achieves

effective management and control of fatigue

consult with mine workers (or coal mine workers) and those doing

the work on fatigue risks (see Obligations for consultation with

workers, on page seven for specific requirements)

identify, analyse and assess fatigue hazards and resultant risk

avoid or remove unacceptable risk and control retained fatigue risks

monitor levels of fatigue risk and the adverse consequences of

retained residual risk

investigate and analyse the causes of serious accidents and high

potential incidents with a view to preventing their recurrence

review the effectiveness of fatigue risk control measures

take appropriate corrective and preventive action

mitigate the potential adverse effects arising from residual risk.

Mining and coal

mining

legislation

obliges

All mining (and coal mining) operations are subject to the Queensland

mining (and coal mining) safety and health legislation. This legislation

requires all obligation holders, including mining operators and SSEs, to

comply with their obligations above to achieve an acceptable level of

6

operators and

SSEs to comply

with their

obligations and

the objects of

the legislation

risk. An object of the CMSH Act and the MQSH Act is to protect the

safety and health of persons at mines (or coal mines) and persons who

may be affected by mining (or coal mining) operations.

Legislation

obliges mine

workers and

persons

generally to

comply with the

Acts,

Regulations and

applicable

safety and

health

management

systems

All persons on mining operations (and coal mining operations) are

subject to the Queensland mining (and Queensland coal mining) safety

and health legislation.

Obligations to ensure an acceptable level of risk is achieved

Fatigue is

managed so an

acceptable level

of risk is

achieved

The CMSH Act, s.30 and QMSH Act, s.27 provides that the systems

must incorporate risk management elements (or procedures) and

practices appropriate for each coal mine (or mine) to—

(a) identify, analyse, and assess risk

(b) avoid or remove unacceptable risk

(c) monitor levels of risk and the adverse consequences of retained

residual risk

(d) investigate and analyse the causes of serious accidents and high

potential incidents with a view to preventing their recurrence

(e) review the effectiveness of risk control measures, and take

appropriate corrective and preventive action

(f) mitigate the potential adverse effects arising from residual risk.

7

Obligations for consultation with workers

Consultation

with workers

according to

specific

requirements of

the legislation

Consultation with coal mine workers regarding fatigue must be in

accordance CMSH Regulation, s.10 and s.42 developing standard

operating procedures that apply to fatigue. This includes, under CMSH

Regulation, s.42 (5), that the site senior executive must consult with a

cross-section of workers at the mine in developing the fitness provisions

and comply with CMSH Regulation, s.42 (6, 6A) and s.8. In developing

the standard operating procedure for fatigue, the requirements of CMSH

Regulation, s.10 apply. Consultation with coal mine workers is also

specified under the CMSH Act, s.64 for changes to the safety and health

management system.

Under the mining and quarrying legislation, consultation with mine

workers is in accordance with the MQSH Act, s.56 (changes to the

safety and health management system) and MQSH Regulation, s.5 for

risk management practices and procedures that apply to fatigue.

Obligations for planning, organisation, leadership and control

SSEs have

obligations for

planning,

organisation,

leadership and

control under

s.42 of the

CMSH Act and

s.39 of the

MQSH Act

Although there is no specific requirement to develop a fatigue risk

management plan, under the CMSH Act, s.42 (f) there is a requirement

for the SSE: to provide for—

(i) adequate planning, organisation, leadership and control of coal

mining operations.

Under the MQSH Act, s.39 (f) the SSE is to provide for—

(i) adequate planning, organisation, leadership and control of

operations.

8

Summary

What is fatigue and why is it a problem? (Chapter 1)

Fatigue is a

state of physical

and mental

impairment

Fatigue can be defined as a state of impairment that can include

physical and/or mental elements, associated with lower alertness,

reduced performance and impaired decision making. There is a direct

link between fatigue and increased risk of being involved in an incident

or accident.

Who needs a fatigue risk management plan? (Chapter 2)

All sites to

conduct a

fatigue risk

assessment to

decide if a

fatigue risk

management

plan is needed

All mines and quarries (under MQHS Act, s.27) and coal mines (under

CMSH Act, s.30) are required to identify whether a fatigue hazard is

present, and if present to assess the risk of fatigue. A fatigue risk

management plan is required if fatigue risk factors are identified during the

risk assessment and the fatigue risk factor tables indicate that these factors

have a medium or high potential.

An operation’s fatigue risk management plan should cover all affected

parties, those who work on planned rosters and unplanned work, such as

overtime call-outs and involvement in emergency response. Commuting

times should also be considered.

Developing and implementing a plan to manage the risk of fatigue

(Chapter 2)

Help to develop

a site-specific

fatigue risk

management

plan

This document is designed to help the mining industry develop a

comprehensive plan to manage fatigue that is specific to their work and

site conditions. It proposes a suggested structure and approach,

however each plan can be expected to be different because it must take

into account the specific hazards, risks and tasks at the mine, and

surrounding conditions. An implementation and management plan must

be developed through a consultative process with stakeholders as

required under legislation. The developed plan should be clearly

documented, be readily available for use and inspection by all relevant

persons, and be reviewed on a regular basis. It should also be

integrated into the overall site safety and health management system,

contractor management arrangements and the operation’s health and

safety management system.

Consultation (Chapter 3)

Involve those

most likely to be

affected by

fatigue

Development of the fatigue risk management plan requires consultation

with all relevant parties, as per the legislation.

Role clarity (Chapter 4)

Identify

everyone’s role

The roles and responsibilities of persons within the organisation who will

have responsibility for developing and implementing the plan should be

identified.

9

Risk management (Chapter 5)

Risk

management is

the key to an

effective fatigue

risk

management

plan

The key aspect of developing a fatigue risk management plan for a

specific workplace is to undertake a thorough risk assessment and

implement a risk management plan (or to exercise a sound and

comprehensive risk management approach considering the complex

multifactorial nature of fatigue). This involves hazard identification and

risk assessment, control of the risks and evaluation of the effectiveness

of the risk controls. Risk assessment is a dynamic process, and the work

environment and systems should be evaluated regularly. The non-work

environment must also be considered. To assist the risk management

process, tools and guidance are provided in checklists, tables 1-4, and

Appendix 3 of this document.

Documentation (Chapter 6)

The plan must

be documented

A fatigue risk management plan must be fully documented and

integrated as part of an overall safety and health management system.

The fatigue risk management system components must be able to be

audited and assessed.

Implementation (Chapter 7)

Risk controls

must be put into

action if the

plan is to be a

success

The fatigue risk management plan must be implemented. Without

adequate risk controls being put in place, the work that has gone into

preparing the fatigue risk management plan will not be useful. Key

issues to consider in implementing the plan include timeframes, training,

roles and responsibilities, resources, communication and participation,

and the effectiveness of controls.

Evaluation (Chapter 8)

The plan must

be reviewed to

make sure it is

working

All aspects of the fatigue risk management plan should be audited and

reviewed at regular intervals to ensure continuing suitability, adequacy

and effectiveness of the controls for managing the risk.

10

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

What is fatigue?

When fatigued,

physical or

mental activity

becomes more

difficult to

perform

Fatigue can be defined as a state of impairment that can include

physical and/or mental elements, associated with lower alertness,

reduced performance and impaired decision making. Signs of fatigue

include tiredness even after sleep, psychological disturbances, loss of

energy, irritability, moodiness and inability to concentrate. Fatigue can

lead to incidents because workers are not alert and are less able to

respond to changing circumstances, thereby putting themselves and

others at risk. Fatigue can also impair decision making, and therefore

cause errors of judgement. As well as these immediate problems,

fatigue can lead to long-term health problems.

What causes fatigue?

Fatigue

develops

directly when

there is

insufficient

sleep quality or

quantity

Fatigue is a complex, multifactor problem that can have many

contributions. There are a number of ‘direct’ causes of fatigue, due to

insufficient sleep quality or quantity. The quantity and quality of sleep

obtained prior to and after a work period can be influenced by:

activities outside of work, such as family commitments, a second job,

or recreational factors

noise or other disturbances during sleep times

individual factors, such as sleeping disorders, health issues, or other

illnesses.

Fatigue most

commonly

arises from

periods of

wakefulness

without

adequate rest

Fatigue is usually considered to have two presentations, acute fatigue

and cumulative fatigue. Acute fatigue is experienced after a one-off or

immediate episode of sleep loss. For example, because of an extended

period of wakefulness, sleep disturbances or inadequate sleep. Ongoing

sleep disruption or lack of restorative sleep can lead to sleep debt and

cumulative fatigue, increasing the risk of fatigue-related incidents or

errors. Fatigue due to the effects of lack of sleep quality or quantity may

be experienced as cognitive (or mental) fatigue, and have effects such

as:

reduced coordination and alertness

changes in emotional function

changes in mental performance or decision making

micro sleeps during tasks.

If sleep loss continues, work performance can deteriorate even further.

Fatigue can

result from work

related or non

work related

causes, or a

combination of

both

Fatigue can result from work related factors, from factors in a worker’s

life outside work or in combination. Fatigue has known effects on certain

tasks or tests, but it is not consistently measurable without specific and

verified testing. Work-related fatigue can and should be assessed and

managed at an organisational level. The contribution of non-work-

related factors varies considerably between individuals. Non-work-

related fatigue is best managed at an individual level.

11

Work-related

causes of

fatigue

In addition to the previous direct factors affecting sleep quality or

quantity, there are additional work related factors that will have an

influence on fatigue development. These inter-related causes of fatigue

can include:

the time of day that work takes place

the length of time spent at work and in work-related duties

the type and duration of a work task, and the environment in which it

is performed

work design (monotony, highly demanding workloads, mentally

challenging work)

organisational factors leading to stressful work environments, such

as bullying, harassment or other psychosocial factors

roster design (e.g. too many consecutive shifts without sufficient

restorative sleep)

unplanned work, overtime, emergencies, breakdowns and call-outs

certain features of the working environment (e.g. noise or

temperature extremes)

commuting times.

Non-work-

related causes

of fatigue

Non-work-related causes of fatigue can include:

sleep disruption due to issues at home

strenuous activities outside work, such as a second job or other

recreational activities impacting on the person’s rest patterns

sleep disorders, insomnia and other diseases

use of alcohol, prescription medication or illegal drugs

stress associated with financial difficulties, domestic responsibilities

etc.

Why is fatigue a problem?

Fatigue

increases the

risk of incidents

and long-term

health problems

Fatigue most commonly causes an increased risk of incidents due to

physical and mental tiredness and lack of alertness. When workers are

fatigued they are more likely to exercise poor judgment and have a

slower reaction time to signals and demands. Fatigued workers are less

able to respond effectively to changing circumstances, leading to an

increased risk due to potential human error. Fatigue is known to also

increase risks off-site, for instance, when the person is driving back to

their home or accommodation.

Cumulative or long term exposure to fatigue, associated with shiftwork,

has been linked to long-term health problems, such as:

digestive problems

heart disease

stress and other psychosocial issues.

The most important reason for fatigue risk management in a work place is to get people

home safely.

12

2. Fatigue risk management plan: development and

implementation overview

2.1 Introduction

A fatigue risk

assessment

must be carried

out

Every mine (or coal mine) must conduct a fatigue risk assessment.

Under the CMSH Regulation the risk assessment must comply with s.42

and s.10. Under the requirements of MQSH Regulation mine and quarries

should incorporate s.6 and s.7. Some sites such as quarries or sites that

operate with limited rosters may find after conducting an assessment, that

they are at an acceptable level of risk of fatigue once the risk assessment

is completed.

A fatigue risk management plan is required if fatigue risk factors (see

Tables 1-4) are identified during the risk assessment.

What a plan

should cover

An operation’s fatigue risk management plan should cover managers,

professional staff, contractors, those who work on planned rosters and

unplanned work such as overtime and call-outs, and involvement in

emergency response. As responding to emergencies can often be

dependent on a very small number of emergency personnel, the scope of

this document does not deal with developing a fatigue risk assessment

during emergency situations. Commuting times should also be

considered.

How to develop

and implement

a fatigue risk

management

plan

This section considers the approach that should be used to develop and

implement the fatigue risk management plan in the workplace and to

integrate it with the health management plan, contractor management

arrangements and with the overall operational health and safety

management system or plan.

2.2 Approach

Policy

commitment

and

consultation are

central

The development and implementation of an effective fatigue risk

management plan should begin with making a policy commitment to the

effective management of fatigue risks in the workplace and establishing

appropriate consultation. Consultation is central to the development and

implementation of an effective plan. The process of development and

implementation is described in detail in the various sections of this

guideline and is outlined in Figure 1.

Everyone’s

roles and

responsibilities

must be

identified

Having committed to the policy and established the consultation

process, it is important to identify the roles and responsibilities of

persons within the organisation who will have responsibility for

developing and implementing the plan. The risk management approach

of identification, assessment, control and evaluation must then be

developed and implemented. This will involve training before

development and as part of the implementation. The fatigue risk

management plan will then need to be documented and implemented.

The effectiveness of the various control measures should be monitored

and evaluated on an on-going basis and the results used to review the

plan on a regular basis. The aim of this process is to produce a fatigue

risk management plan, then to implement the plan and to integrate this

process with the overall operational safety and health management

system. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

13

Figure 1 Fatigue risk management plan: development and implementation overview.

14

An effective

fatigue risk

management plan

details a

systematic

program

In summary, the development and implementation of an effective fatigue

risk management plan requires:

making a policy commitment to effective fatigue risk management

consultation with mine workers (or coal mine workers)

establishment of roles and responsibilities

risk identification, assessment, control and evaluation

training and review of training at relevant intervals in the process

documentation of the plan

implementation of the plan

development and implementation of assessment and monitoring

procedures

review and resultant modification of the plan if required.

2.3 Resources needed for an effective fatigue risk management plan

Appropriate

resources are

essential

Those responsible for the development and implementation of the

fatigue risk management plan must ensure that appropriate resources

are made available as per their legislative requirements under

Queensland legislation. In addition, as fatigue is a complex,

multifactorial problem, some sites may need to ensure that these

resources include those with the appropriate knowledge and

understanding of fatigue.

Further advice on accessing external resources is found in Appendix 3.

15

3. Consultation

3.1 Introduction

Consult with

workers most

likely to be at

risk

Consultation with those workers performing the work is important as they

are likely to have the best practical understanding of work processes and

the potential fatigue as a result of work-related or individual factors. Such

consultation is required under the mining and coal mining Acts as

discussed below. In addition, mine workers (or coal mine workers) are the

persons most likely to be at risk of developing the longer term health

effects associated with ongoing fatigue.

A process of

consultation

must

underpin the

fatigue risk

management

process and

plan

Key aspects of consultation relevant to the development of a fatigue risk

management plan include:

consultation by the operator/SSE with the workers to enable them to

contribute to decisions affecting their safety and health at work

regarding fatigue

information that must be shared includes matters that affect or may

affect the safety and health of workers

consultation with coal mine workers in accordance with the CMSH Act,

s.64 (changes to the safety and health management system) and

CMSH Act, s.10 and s.42 for developing standard operating

procedures that apply to fatigue

consultation with all other mine workers in accordance with the MQSH

Act, s.56 (changes to the safety and health management system) and

MQSH Regulation, s.5 for risk management practices and procedures

that apply to fatigue.

There are

different

ways to

consult

Consultation must be undertaken as required by legislation.

16

4. Roles and responsibilities

4.1 Operator/SSE

Operators and

SSEs have the

main

responsibility

for controlling

fatigue risks

Operators and SSEs hold the fundamental obligation for managing the

risks associated with fatigue. The fatigue risk management plan should

nominate those responsible for different actions. Some suggested

responsibilities for fatigue risk management is provided in Section 4.3. It

is the operator/SSE’s responsibility to make sure that fatigue is

managed using the risk management approach described in this

guidance note, or in another way that achieves the same result. The

fatigue risk management plan or policies should be signed off by the

most senior appropriate person representing the operator. Adequate

resources should be provided to allow the plan to be implemented.

4.2 Mine workers (or coal mine workers)

Mine workers

(or coal mine

workers) must

not put

themselves at

risk of being

fatigued

Mine workers (or coal mine workers) are responsible for ensuring that

their actions and behaviour do not create or exacerbate risks. They

should ensure that they use the opportunities provided to obtain sleep,

report occasions when adequate rest is not obtained and present and

remain fit for work.

4.3 Who should be involved in implementation of fatigue prevention

and management

In deciding who should be involved in implementing fatigue prevention and management,

consider existing roles and responsibilities within the organisation. Not all sites will have or

need all of the roles described below or have a legislative obligation to assign these roles.

Suggested roles and responsibilities for an effective fatigue risk management approach are

listed below.

Role

Responsibility

Senior

managers

(operators and

SSEs)

setting realistic timeframes, outcome measures and

accountabilities

ensuring the risk management process is followed

ensuring managers are accountable for fatigue risk management

performance including:

o provision of necessary resources and other support

o effective implementation of fatigue prevention and

management within the safety and health management system

o ensuring adequate consultation

o ensuring reporting of fatigue risk management issues and

outcomes

o ensuring that fatigue is identified both proactively in risk

assessment processes as well as reactively in incident

investigations in a ‘no blame’ culture

o ensuring training and education is conducted.

17

Safety and

health ‘manager’

or site advisor

for fatigue

(can be included

in existing

Safety and

Health

portfolios)

assisting in developing and maintaining a list of safety critical tasks

for fatigue

assisting operational areas to develop realistic schedules for

fatigue risk management and control

ensuring that risk assessments and solutions are documented

assisting in the development of controls and recommending

appropriate controls for implementation

liaising with operational areas on implementing the integration of

fatigue prevention and management into planning and decision

making on rosters, call-outs, training, etc

acting as a resource for the risk assessment teams and

maintaining knowledge base on fatigue issues

ensuring that appropriate change management systems for

changes to worker commuting arrangements is communicated and

monitored

reporting regularly on progress.

Those

participating in

fatigue risk

assessment

team for each

operational area

assisting with identifying highly fatiguing or safety critical tasks for

fatigue

assisting with identifying contributing risk factors for fatigue in the

work environment or task conditions

participating in the fatigue risk assessment

assisting with evaluating effectiveness of fatigue risk management

implementation

assisting with monitoring and reviewing the systems and

maintaining knowledge on fatigue

contributing feedback on effectiveness of training for fatigue.

All mine workers

(or coal mine

workers)

participating in fatigue training

following procedures to minimise and manage the risk of fatigue

and maintaining FFW

reporting on individual factors or other factors contributing to

fatigue

reporting incidents (i.e. where fatigue was a contributing factor)

participating in bringing forward issues to the site safety and health

representatives when identified through the site reporting

requirements

assisting with fatigue risk assessments and surveys.

Adapted from the Industry and Innovation NSW 2009 publication, Managing musculoskeletal

disorders – A practical guide to preventing musculoskeletal disorders in the NSW mining and

extractives industry.

4.4 Approach

The process

should be

flexible enough

to deal with

different views

The fatigue risk management plan must be developed and implemented

in a consultative, participative manner involving all affected mine

workers (or coal mine workers) throughout the process, and in decision-

making about the outcomes. During the consultative process, coal

workers should be given the opportunity to consult with industry safety

and health representatives if relevant. The plan is likely to be most

effective when it is developed through appropriate consultation with

workers. The sensitive nature of many of the issues involved in this area

means that establishing and communicating the fatigue risk

management process is important.

18

Consultation

must

accommodate

the variable

hours people

work

Fatigue has a direct influence on the work/life balance of all who work in

the industry. Hours of work and fatigue have an effect on the individual

at work and off site. Communication, consultation and training should

reflect the variability of working arrangements of contractors, and others

on site.

19

5. Fatigue risk management

5.1 Introduction

Risk

management is

at a minimum a

four-step

process

containing a

number of

elements.

In the CMSH

Regulation

these elements

are described in

s.6 and under

the MQSH

Regulation they

are described in

s.6-11

This chapter considers fatigue risk management in detail. Risk

management encompasses identification, assessment, control and

monitoring/review of hazards that pose a meaningful risk to the safety

and health of mine workers (or coal mine workers) and visitors to the

mine (or coal mine). Under the CMSH Regulation, s.6 the basic

elements include:

(a) risk identification and assessment

(b) hazard analysis

(c) hazard management and control

(d) reporting and recording relevant safety and health information

and data.

To ensure that the processes followed on-site meet the intent of this

document, these steps should incorporate at least:

risk identification - involves identifying the activities that may pose

a risk

hazard analysis (or risk assessment) - describes the process of

evaluating the extent of the risk arising from exposure to the hazard

hazard management and control - is the process of addressing

the risk by eliminating or minimising its affect

monitor and review - is the process of checking the extent to

which the control measures have been successful.

In addition, there may be requirements to report and record relevant

safety and health information and data.

Assessing risks

helps set

priorities

Risk assessment is a dynamic process, with risks being assessed and

prioritised and the impacts of the controls being evaluated regularly.

Risk

assessments

must be done

by people who

are trained and

have the

knowledge of

the hazards

Risk assessment must involve appropriate consultation between

relevant parties. In particular it is important that a cross section of

workers potentially affected by fatigue hazards have an opportunity to

provide input to the risk assessment process. Workers’ practical

knowledge of the tasks and associated hazards and risks provides an

extremely valuable input into the risk assessment process. However, a

risk assessment in a complex technical area such as fatigue can be a

demanding undertaking and it is essential that those carrying out the

risk assessment have sufficient knowledge of the hazards and the direct

and contributing risk factors to undertake such an assessment. In some

situations this will involve bringing in expertise in fatigue from outside

the organisation.

Risk

assessments

incorporate

appropriate

techniques or

standards

A number of standards exist for undertaking risk assessments. For

example, the National Minerals Industry Safety and Health Risk

Assessment Guideline (http://www.mishc.uq.edu.au/Resources.aspx)

provides guidance on risk assessment that incorporates some risk

factors for fatigue. The coal mining Recognised Standard 02 Control of

risk management practices, is also a relevant standard for providing the

required documentation for the risk assessment.

20

Fatigue, along with other complex multifactorial ergonomics and psycho-

social hazards, requires more qualitative techniques for risk

management and consideration of multiple factors, based on evidence

from content experts. Although this guide may present new concepts

such as fatigue risk factors and other information that is solely focused

on fatigue hazards and controls, most sites will be able to incorporate

the contents of this guide into their risk assessment standards. Further

recommended considerations for fatigue risk management in line with

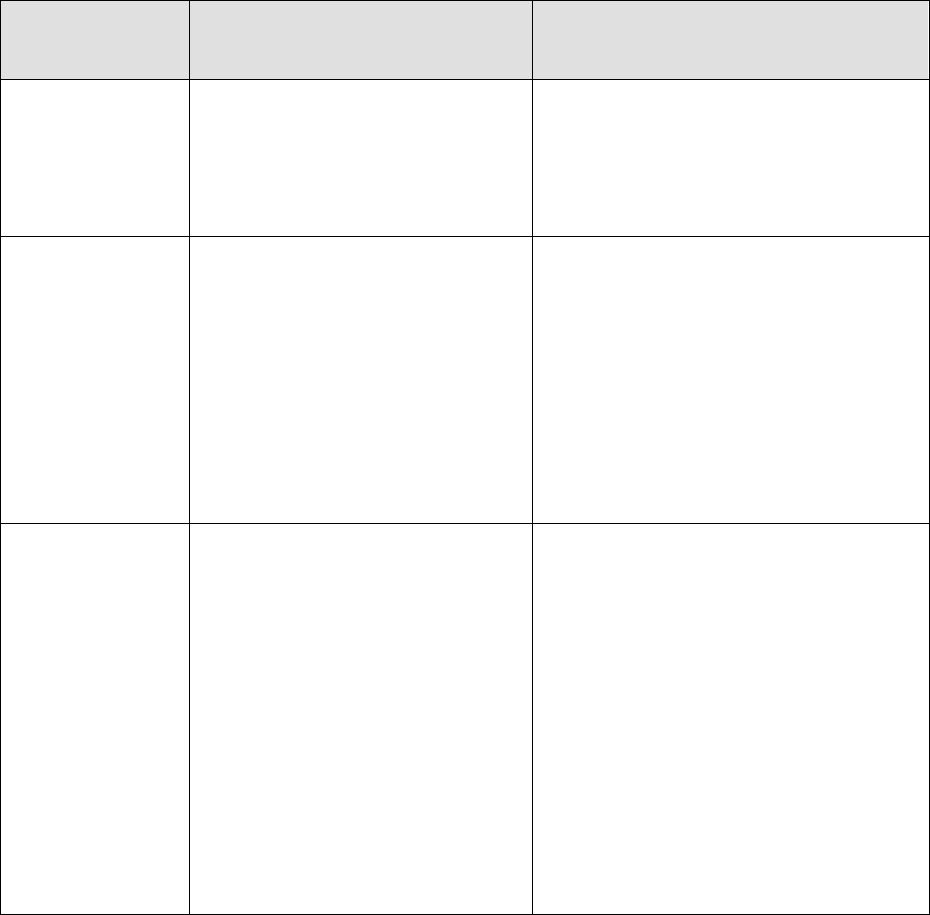

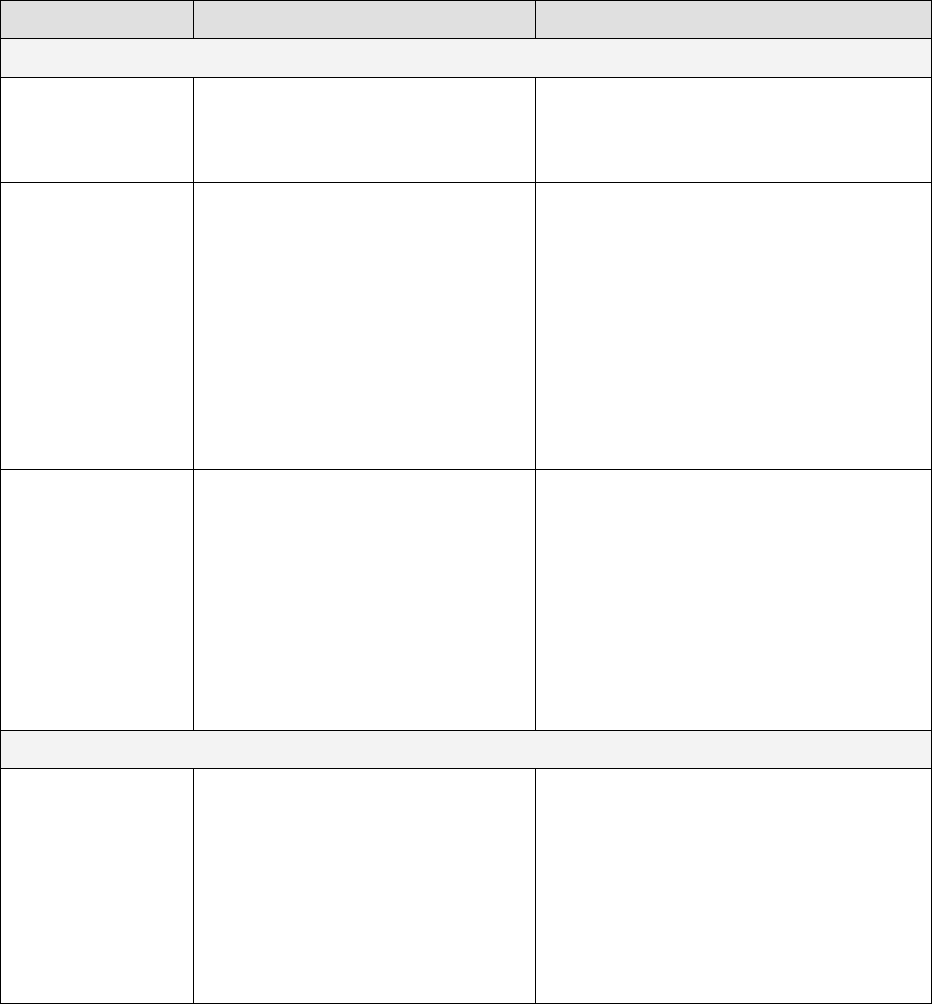

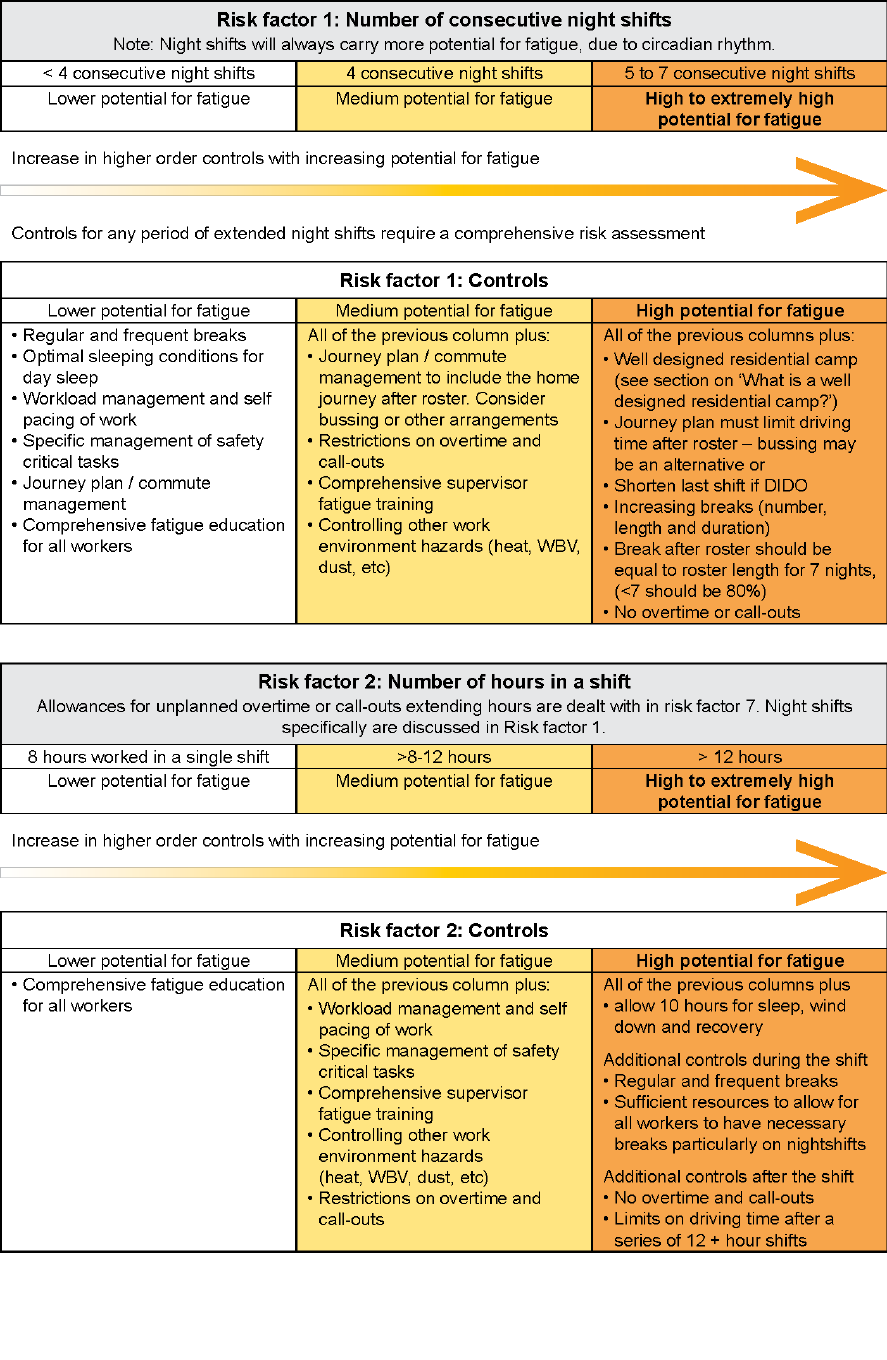

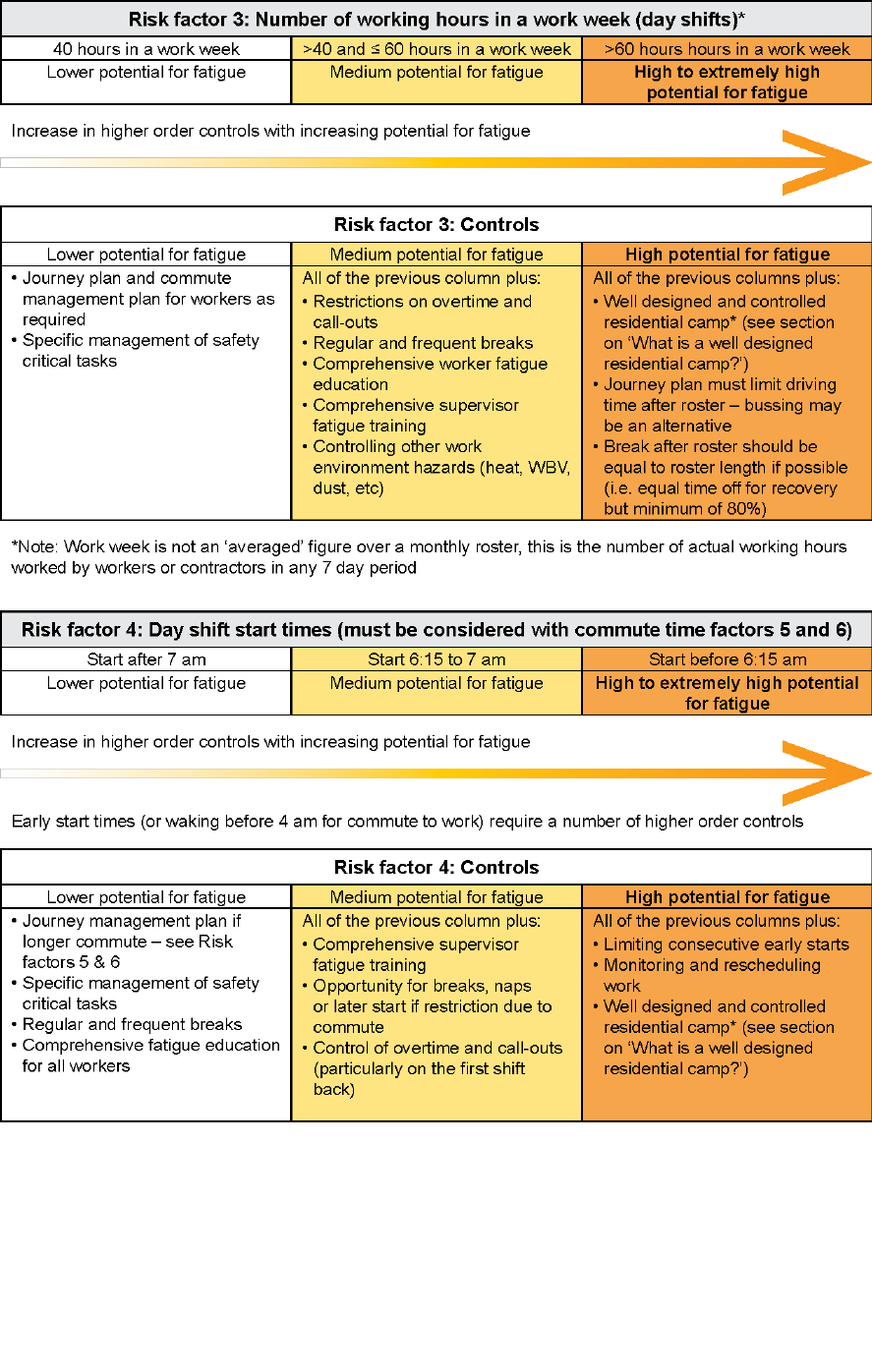

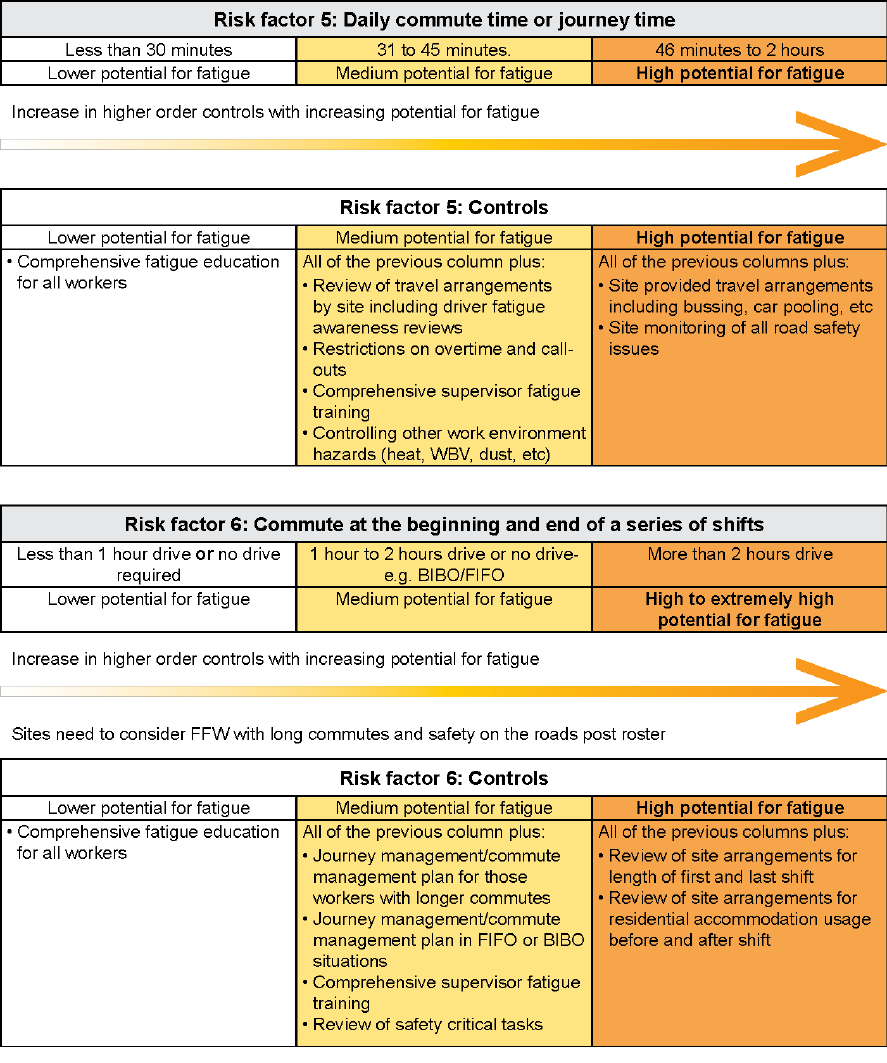

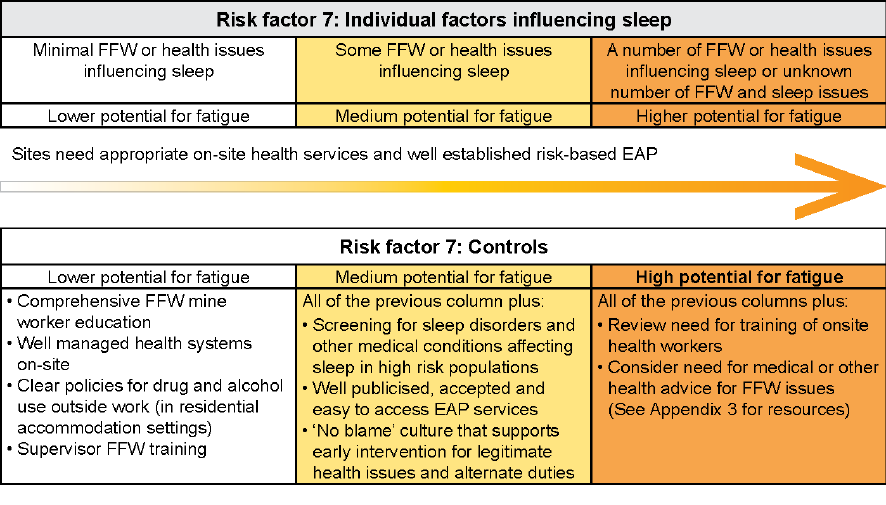

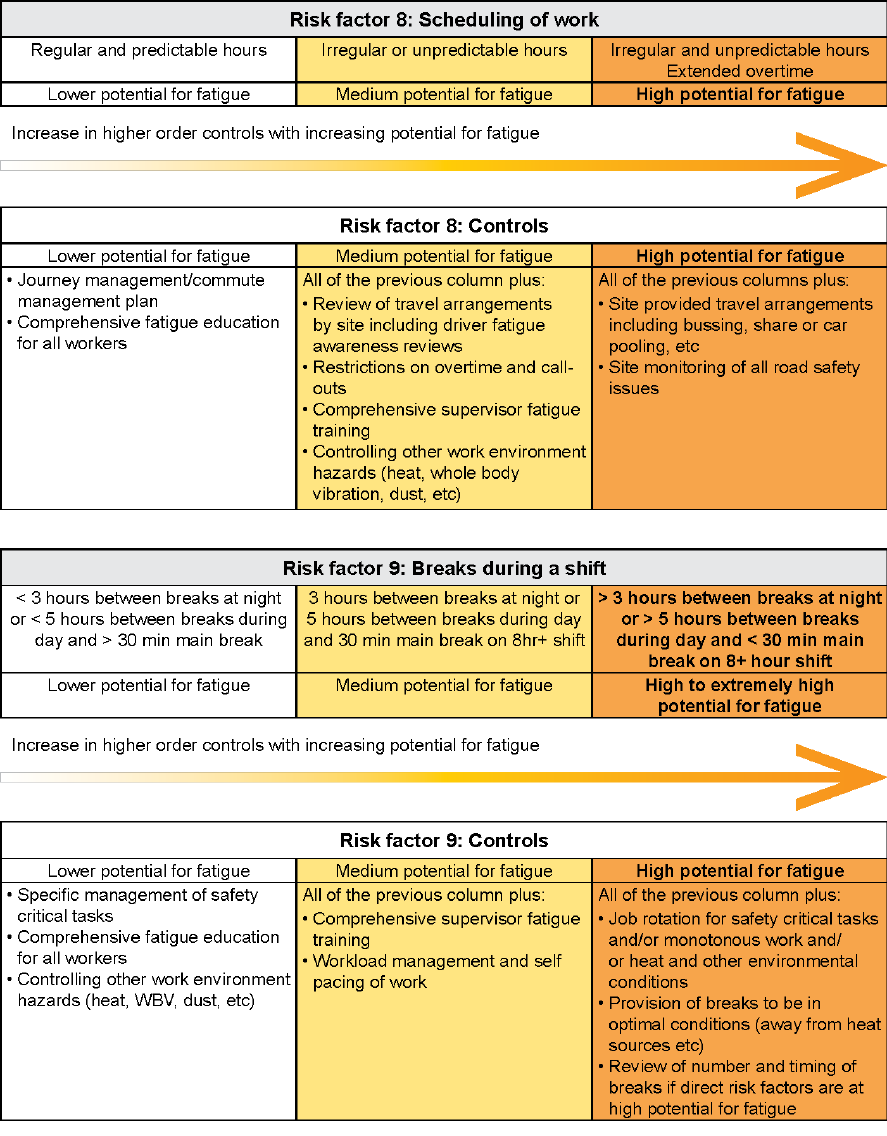

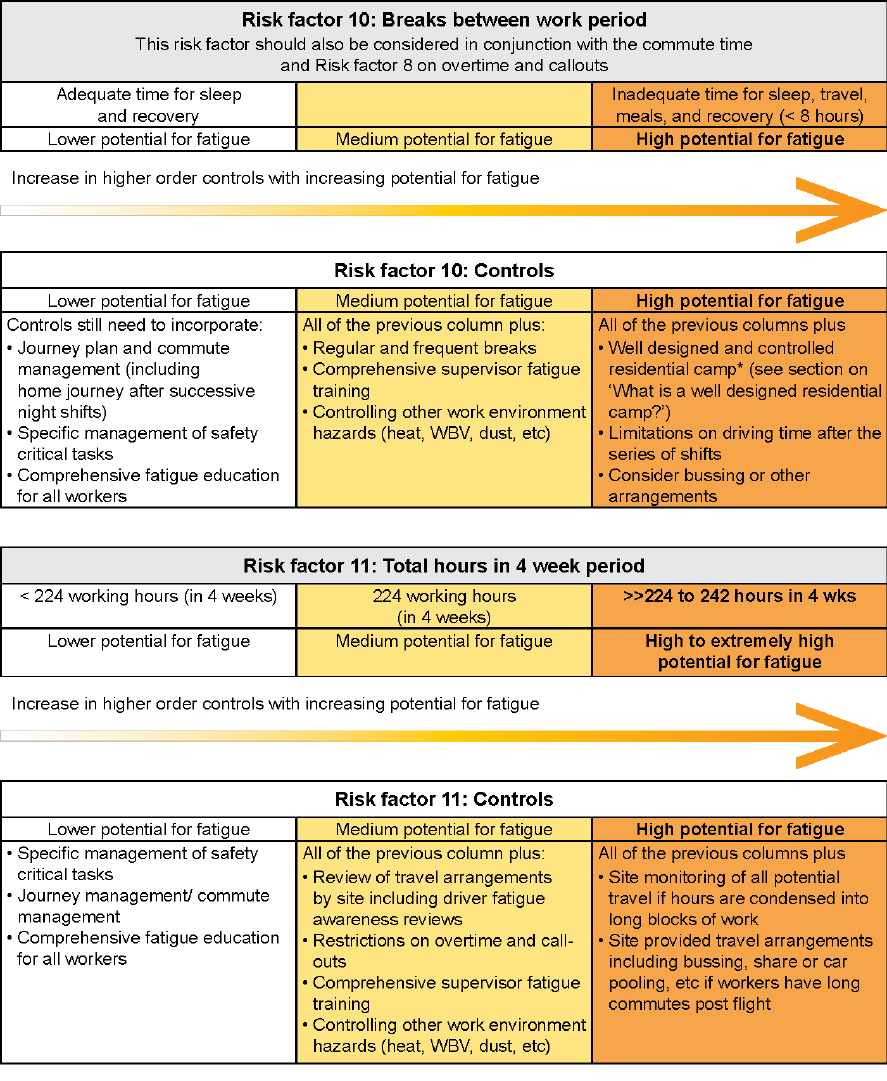

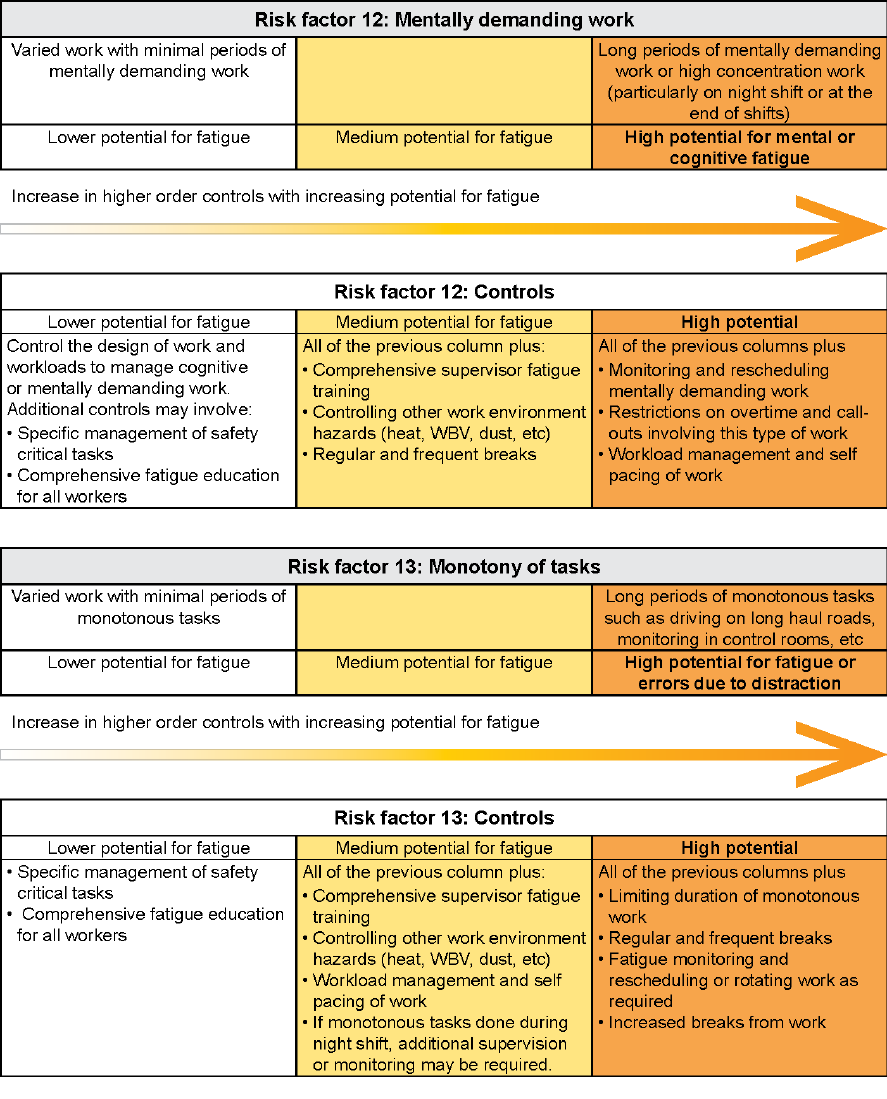

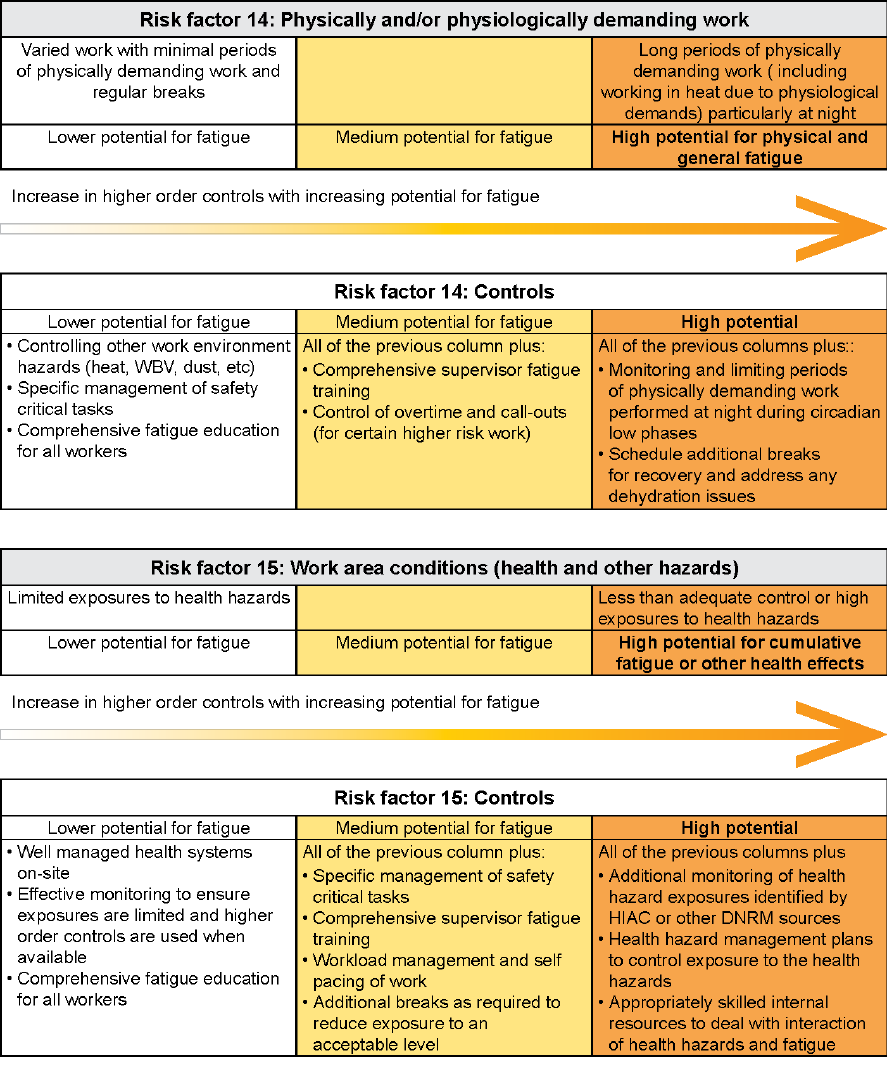

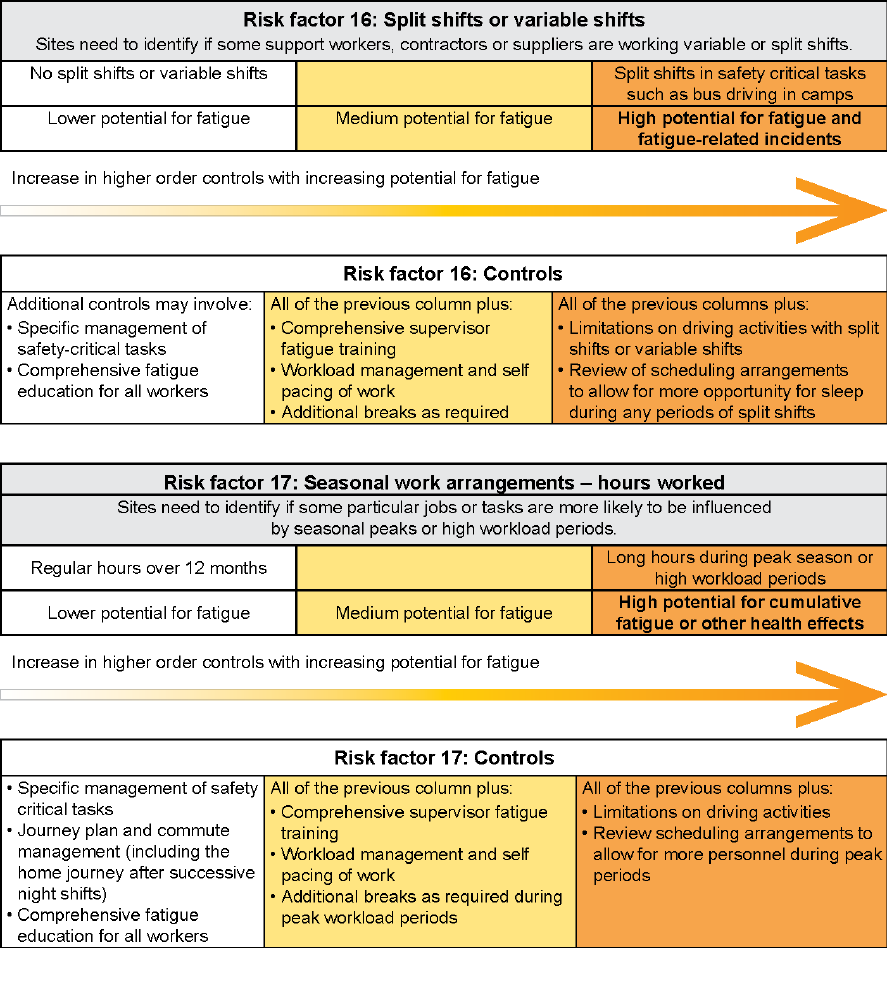

standards are provided in Appendix 4.

Useful documents to consult when developing the fatigue risk

management plan or to incorporate into existing risk assessments can

be found in Appendix 3.

Risk control

measures follow

the hierarchy of

control

The key component of the risk management process is to develop

effective controls, based on current and best practice, using the

hierarchy of controls. There are many forms of the hierarchy, but

essentially the control measures, in descending order of preference,

consistent with mining and quarrying legislation, are as follows:

elimination

substitution

isolation

engineering

administrative approaches

personal protection.

Emergency

situations

require

consideration

In emergency situations the focus of the site should be on dealing with

the emergency. This may mean that it is not possible to fully control all

the fatigue risk factors as described or recommended in Tables 1-4. As

fatigue can impair decision making in emergencies, it is still important to

consider the effects of fatigue on emergency personnel and those

dealing with crises. These effects should be considered on an individual

basis.

5.2 Hazard identification: identifying factors that may contribute to

fatigue

Identifying

common factors

that contribute

to fatigue

Risk factors for fatigue can be identified in a variety of ways. Most sites

should start with consulting a cross section of the workforce. In addition,

examining records to look at incidents and health concerns that have

occurred previously often provides useful information. Other guidance

relevant to mining is also available and should be considered for a

comprehensive list of fatigue risk factors (see Appendix 3).

Based on a number of different sources, the common factors that can

contribute to the development of fatigue include:

work scheduling and planning

long or excessive commuting times

work environment conditions, and mental and physical demands of

work

lack of restorative sleep

individual and non-work factors.

These factors will potentially influence:

21

1. sleep opportunity and quality, including recovery or restorative sleep

(pre-shift, during roster and post shift)

2. extended wakefulness (length of time individuals are required to be

awake) and onset of fatigue (pre-shift, during and at the end of the

roster)

3. work tasks, environment and site conditions contributing to fatigue

4. individual and personal factors influencing fatigue.

Work

scheduling and

planning

The way work is planned and scheduled, the time work is performed and

the amount of time worked can increase the risk of fatigue. Scheduling

work in a way that fails to allow workers enough time for travel to and

from work and/or allow for sufficient time for sleep can cause fatigue.

Working at times when workers are biologically programmed to sleep

(which can disrupt a worker’s body clock) and working for long periods

of time can also produce fatigue. Particular issues include:

night shifts, including the number of consecutive night shifts

long hours of work in a single shift, or across a shift cycle, or

because of on-call duties. This includes travel time especially for

remote sites

short breaks between or within work shifts

shift start/finish times (e.g. a start or finish time between 10pm and

6am may interrupt usual optimal sleep times)

changes to rosters

unplanned work, overtime, emergencies, break downs and call-outs

less than adequate opportunity for restorative sleep.

Work

environment

conditions

Working in harsh and/or uncomfortable environmental conditions can

contribute to the risk of fatigue in a number of ways. Heat, cold, noise

and vibration are some of the environmental conditions that can

increase the likelihood of fatigue onset and impair worker performance.

Excessive

commuting

Depending on shift lengths, having to travel for long distances before or

after work, particularly on a daily basis for a long series of shifts, can be

a contributor to fatigue. This will depend on the means of transport and if

a person is in control of a vehicle.

Mental and

physical

demands of

work

The mental and physical demands of work can contribute to a worker

becoming impaired by fatigue in a number of ways. Concentrating for

extended periods of time, performing repetitious or monotonous work or

performing work that requires continued physical effort can increase the

risk of mental or physical fatigue.

Individual and

non-work

factors

In addition to the work-related factors that contribute to fatigue, it is

important to identify factors that cause fatigue due to lack of sleep

quality or quantity. These include:

lifestyle e.g. children and child-care responsibilities, voluntary work,

having more than one job, level of fitness, social life or diet

home environment e.g. noisy neighbours or a bedroom that is too

hot or not dark enough for day-time sleep

health or medical conditions e.g. insomnia, sleep apnoea, pain or

other health problems or alcohol/drug issues

medication

other factors e.g. stress.

22

Effect of

exposure for

longer periods

When taking a risk management approach to fatigue it is very important

to look at how fatigue and long working hours in general can interact

with other workplace hazards. Exposure to some hazards can be

increased when working extended hours – e.g. heat, whole body

vibration (WBV), manual tasks, and exposure to hazardous chemicals,

dust and noise.

5.3 Risk assessment

Risk

assessments

consider two

aspects -

likelihood and

severity

One of the keys to effective risk management is to properly assess the

risks arising from a hazard. Assessing hazards related to fatigue means

looking carefully at the identified fatigue risk factors to decide whether

they have been eliminated or adequately controlled to an as low as

reasonably achievable level. These fatigue risk factors have been

developed to ensure that relevant research and fatigue knowledge is

incorporated into the risk assessment.

Each hazard should be examined in detail to determine its influence on

sleep opportunity and quality, the length of time individuals are required

to be awake, the intensity or monotony of the work, and the work

environment contributions. This requires:

input from a cross-section of workers

reference to hazards database

reviewing errors and incidents to determine any contribution that

fatigue has made, including use of safety bulletins or other incidents

from other sites

the use of relevant fatigue data and information (such as fatigue

guidance material, industry codes of practice, relevant fatigue

research and good practice, including this guidance note)

if necessary, advice from experts in the field.

The results of the risk assessment should be clearly recorded. It is

important to remember that fatigue is a multi-factorial problem, and

some factors interact to increase fatigue and the risk of a fatigue-related

incident or errors.

For example, the combination of poor quality and /or insufficient length

of sleep with an extended shift and/or a number of consecutive night

shifts and/or performing a monotonous task for long periods, is likely to

have a higher risk of fatigue.

The common fatigue risk factors are shown in the Fatigue risk factor

checklist in four sections, grouped into the factors that have an

influence on the following:

1. (Section 5.3.1), sleep opportunity and quality including restorative

sleep (pre-shift, during roster and post shift)

2. (Section 5.3.2), extended wakefulness (length of time individuals are

required to be awake) and onset of fatigue (pre-shift, during roster

and post shift),

3. (Section 5.3.3), effect of the work tasks, environment and site

conditions on fatigue

4. (Section 5.3.4), individual and personal factors influencing fatigue.

23

5.3.1. Fatigue risk factors influencing sleep opportunity and quality

There is a significant amount of fatigue research and guidance relating to the role of work

scheduling and planning on sleep opportunity and quality. The main components of the

scheduling and planning on fatigue risk deal with:

opportunity for sleep before first shift and between successive shifts during the roster

sleep quality, and day sleeping during the roster compared to night sleeping (the body’s

preference is for night sleep)

changes to the circadian cycle or ‘body clock’ due to changes in roster, overtime, call-

outs, or split shifts

commute time influencing opportunity for sleep

on-site arrangements and off-site accommodation and surrounds affecting sleep quality

and opportunity for sleep.

There are a number of fatigue risk factors that will differ between sites, for example, some

fatigue risk factors influencing sleep opportunity and quality during the roster will differ

between FIFO (fly in/fly out) and DIDO (drive in/drive out).

The information in the table on pages 36 -44 is adapted from the NSW fatigue guidance

document, Fatigue - prevention in the workplace.

a) Work scheduling and planning

Work

scheduling and

planning

Aspects to consider

Why consider these issues?

Night shifts,

including the

number of

consecutive

night shifts

Are too many consecutive night

shifts worked consecutively to

allow adequate recovery?

For example:

Is more than eight hours

work required over night

shift?

Are more than four

consecutive 12-hour night

shifts worked?

Are more than five

consecutive 10-hour night

shifts worked?

Are more than six

consecutive 8-hour night

shifts worked?

Increased fatigue risk has been

found with exceeding some of

the above combinations of night

shifts (Folkard, 2007)

Research indicates that sleep

during the day (e.g. after night

shifts) is not as good quality as

during the night (Baker et al,

1999).

The longer the length of the night

shift, the more time is spent active

and working when the body is

designed to be asleep.

A longer series of night shifts can

be associated with cumulative

fatigue due to lack of restorative

sleep.

24

Shift start/finish

times

Do any shifts start or finish

between 10pm and 6am?

(See also commute time)

Research shows that early shifts

(especially when people have to

wake more than two hours before

their normal wake time) can cause

shortened periods of sleep

(Folkard, 2007). This can be a

particular problem on the first day

shift of the roster, especially with a

long commute.

Are split shifts required or

offered?

Split shifts usually require that

sleep is broken into two short

periods rather than one long

period.

Shift rotation

during roster

Is there a switch from day to

night or night to day during

the same roster?

The body needs time to adapt to

changes required to the body

clock and sleep between day and

night shifts. Research (Baker and

Ferguson, 2004) shows that a

frequent change in working time

can cause even more fatigue as

the body tries to find equilibrium.

Long hours of

work across a

roster cycle

Do hours of active work (total

time spent at work including

overtime) exceed 84 hours in

any seven days, or 242 hrs

in four week period?

Longer periods at work require

longer periods for recovery, with

the additional problem of

cumulative fatigue. Fatigue can

increase as other factors start to

affect sleep.

Short breaks

between work

shifts

Is there less than seven

hours per night (or less than

50 hours in seven days)

allocated for sleep between

shifts? Is the break between

shifts less than 10 hours?

Are there less than two

consecutive night time sleep

opportunities (48 hours)

every seven days?

Most people need between six to

eight hours sleep to be ‘adequate’

for rest and recovery. Shorter

periods of sleep than a person’s

normal requirement can cause

fatigue as well as other problems.

Sleep is the time the body

regenerates, as well as allowing

for memory consolidation, learning

and other brain functions.

Most guidance recommends more

time to recuperate after night

shifts as day sleep is sometimes

more fragmented. Ten hours

break will allow for a minimum

seven hours for sleep, and two

hours for wind up/ wind down.

25

b) Changes in roster, overtime, call-outs, or split shifts

Work

scheduling and

planning

(changes to

rosters or

scheduling)

Aspects to consider

Why consider these issues?

Long hours

because of on-

call duties or

unplanned

overtime

Are there irregular and

unplanned schedules as a

result of call-outs?

Is there inadequate recovery

time after call-outs allowed

(e.g. insufficient break to get

adequate sleep)?

Does unplanned overtime or

routine overtime extend the

working day or working week

beyond 84 hours in any

seven days, or 242 hrs in

four weeks?

The body performs best under a

routine of waking, sleeping, and

eating at certain times. Disruptions

and adjustments to routine and

the body clock can increase the

risk of fatigue.

Unplanned or unscheduled

overtime or call-outs can cause

more difficulty in scheduling

sufficient sleep and cause acute

or cumulative fatigue.

Changes to

rosters

Do workers get sufficient

notice of roster changes?

Is there a possibility that

fatigue risk management

won’t be considered in roster

changes?

This may influence scheduling for

sufficient restorative sleep

between shifts as well as rosters

and the ability of the body to adapt

to changes.

Number of ‘yes’ responses for 5.3.1 (‘a’ and ‘b’): _____________

26

c) Commute time influencing opportunity for sleep

Work

scheduling and

planning

(commute)

Aspects to consider

Why consider these issues?

Long commute

for first shift

Do workers have to travel

more than two hours to

arrive on-site for the first

shift?

Sites with organised travel (e.g. fly

in/fly out) should be aware that

those who are commuting for long

distances may have already

limited sleep opportunity. The first

day shift in particular has been

found to be difficult due to the

transition between the ‘normal’

sleep wake times of workers at

home, and the adapted sleep

wake times required for work.

Long commute

during roster

Do workers have to travel

more than one hour in each

direction?

Commute times will have an

impact on sleep opportunity. If we

add in commute times of one

hour, with >12 hr shift length, then

this can influence the opportunity

for sleep and fitting in other daily

activities

Does this have an influence

on wake time for day shifts?

Workers with a longer commute

will have to wake in the ‘critical

zone’ before 4 am and this will

influence the length of sleep they

will have.

Number of ‘yes’ responses for 5.3.1c: _____________

If you have answered ‘yes’ to a number of questions in the checklist, continue with the

other sections in the checklist and then proceed to the risk assessment and control

tables 1-3.

27

5.3.2. Length of time awake and factors influencing onset of fatigue

(direct and contributing risk factors)

There is a significant amount of fatigue research showing that extending wakefulness can

lead to fatigue and some loss of performance. Dawson and Reid (1997) showed the longer

people were awake and not able to sleep, the greater their performance decreased. For a

number of participants in the study, when they stayed awake for more than 17 hours they

showed performance deficits that were similar to a blood alcohol concentration of .05

g/100ml). The length of time awake is also linked to the time of the circadian phase, but it is

important to look at the length of hours worked, breaks and the demands of the actual work.

The main components for wakefulness and fatigue onset that interact to change fatigue risk

include:

Length of scheduled shift and breaks

Commute time influencing time awake and active

Work organisation and other workload factors

Task and environmental factors

As with the previous section, there will be differences between FIFO, BIBO and DIDO, as

well as other differences between sites.

a) Length of time awake (wakefulness)

Risk factor

Length of time

awake

Aspects to consider

Why consider these issues?

Long hours of

work in a single

shift. This includes

overtime, call-outs

and travel time

Does one shift involve more

than 12 hours in a day

(including call-outs)?

There is an increased risk associated

with extended shifts beyond 12 hours.

This depends on work performed,

number and frequency of breaks

during the shift and other factors.

Long daily

commutes

Do workers have to commute

for one hour or longer after a 12

hour shift?

The long daily commute extends the

time workers are awake as well as

the opportunity for sleep.

Long commute at

the end of roster

or end of set of

shifts

Do workers have to drive more

than two hours to arrive at their

home at the end of the roster or

set of extended shifts?

Sites located at significant distances

from workers’ homes need to

consider that workers may have

accumulated a sleep debt.

Number of ‘yes’ responses for 5.3.2a: _____________

28

b) Risk factors influencing onset of fatigue (breaks and workload management)

Breaks and

workload

management

Aspects to consider

Why consider these issues?

Less than

adequate

scheduled work

breaks

Are breaks within shifts not

long enough or frequent

enough to allow workers to

rest, refresh and nourish

themselves?

Folkard (2007) and other

researchers have found that the

length of time between breaks

(e.g. greater than five hours), and

number of breaks has an impact

on overall risk of incidents.

Workload,

psychosocial

and mental

demands

Do jobs involve high

demand, but low control?

Are there poor social

relations at work, e.g.

bullying?

Is there low social support

from peers and supervisors

at work?

Is there low recognition for

the effort involved in the

work?

There are a number of risk factors

for stress, and fatigue. Poor work

organisation, work relationships

and other factors can create

significant mental or cognitive

‘overload’. This will influence

fatigue and performance.

Workload

management of

complex

physical or

mental tasks

Are complex or prolonged

physical or mental tasks

undertaken on night shift?

Are complex, difficult or

strenuous tasks required at

the start or end of night shifts

or extended shifts?

Is high vigilance and/or

concentration required?

Are there different demands

that can be difficult to

combine?

Are tasks requiring sustained

physical or mental effort

undertaken on night shift?

Mental, physical and psychological

workload is influenced by

circadian rhythm as well as other

factors.

It is more likely errors will be made

and influenced by fatigue under

certain situations, especially for

high risk tasks.

Number of ‘yes’ responses for 5.3.2b: _____________

If you have answered ‘yes’ to a number of questions in the checklist, continue with the other

sections in the checklist and then proceed to the risk assessment and control tables 1-3.

Some risk factors are considered ‘Direct’ risk factors and will require additional controls. If

you are not sure on the answers, gather more information and then proceed to the risk

assessment and control tables.

29

5.3.3 Effect of the work tasks, environment and site conditions on

fatigue and other influences on health (contributing risk factors)

The interaction between the work performed, the work environment and the task needs to be

considered when designing rosters and considering control measures.

A number of differences can exist for a fatigue-related incident (both in opportunity and

consequence) between occupations or jobs on-site. For example, Larue et al. (2009)

demonstrated that very monotonous tasks including driving for long periods on straight

stretches of road increased the onset of micro sleeps, loss of concentration, drifting between

lanes, etc. The main components for fatigue onset that can increase fatigue risk include:

mental, physical and physiological demands of work

adverse working conditions and prolonged exposure to health hazards.

Risk factor

Aspects to consider

Why consider these issues

Mental, physical and physiological demands of work

Repetitive or

monotonous

work

Do jobs involve repetitive or

monotonous work, e.g. haul-

truck driving and control

room operations?

Monotonous tasks such as driving

can increase fatigue.

Sustained

physical or

mental effort

Is the work physically and or

mentally demanding?

Is there time pressure due to

a heavy workload?

Is work fast paced? If yes,

can workers vary work pace

or work tasks as desired?

Is work intensive?

Do workers lack sufficient fit

for purpose equipment to

carry out the task?

Certain jobs or tasks can increase

physical or mental fatigue and the

onset of fatigue during the day.

Some work may require longer

breaks or recovery from fatigue

inducing conditions.

Adverse working

conditions

Do adverse working

conditions exist, e.g.

exposure to:

o Noise?

o Heat or dehydration?

o Sunlight or UV?

o Cold?

o Dust?

o Whole body vibration or

hand arm vibration?

Many health hazards influence

fatigue onset or increase the need

for breaks for recovery/rest

between shifts.

Effect of exposure during extended shifts

Increased

exposure to

health hazards

Do the adverse working

conditions above require

adjustments to exposure

time or further monitoring?

Are workers exposed to

hazardous substances such

as fumes, chemicals etc?

Note that exposure

standards will need to be

Exposure to a number health

hazards will cause an onset of

fatigue.

Consider overall health effects as

well as fatigue with extended

exposures.

30

adjusted for working more

than eight hours (see

Tiernan and van Zanten,

1998)

Number of ‘yes’ responses for Section 5.3.3: _____________

5.3.4. Effect of individual and personal work factors (Direct risk factor)

Fatigue is experienced differently between individuals, and there is a significant amount of

research addressing the impact of individual health and other factors on fatigue. A number of

health issues can have a negative influence on sleep quantity and quality. Some common

conditions include insomnia, obstructive sleep apnoea, chronic pain, and depression. Some

conditions may have an influence sleep over a longer period, and some are short term (e.g.

insomnia due to personal or family life issues).

A number of non-health related issues can also have a negative influence on fatigue and the