St. Cloud State University St. Cloud State University

theRepository at St. Cloud State theRepository at St. Cloud State

Culminating Projects in Education

Administration and Leadership

Department of Educational Leadership and

Higher Education

8-2020

The Perceptions of School Counselors on Preparedness for The Perceptions of School Counselors on Preparedness for

Serving Gifted Students Using Bullying Prevention and Serving Gifted Students Using Bullying Prevention and

Intervention Strategies Intervention Strategies

Rick Halley

Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/edad_etds

Part of the Educational Leadership Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Halley, Rick, "The Perceptions of School Counselors on Preparedness for Serving Gifted Students Using

Bullying Prevention and Intervention Strategies" (2020).

Culminating Projects in Education Administration

and Leadership

. 71.

https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/edad_etds/71

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Educational Leadership and

Higher Education at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in

Education Administration and Leadership by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For

more information, please contact [email protected].

The Perceptions of School Counselors on Preparedness for Serving Gifted

Students Using Bullying Prevention and Intervention Strategies

by

Rick L. Halley

A Dissertation

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of

St. Cloud State University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree

Doctor of Education in

Educational Administration and Leadership

August, 2020

Dissertation Committee:

John Eller, Chairperson

Elizabeth Fogarty

David Lund

Plamen Miltenoff

2

Abstract

Despite 40 years of significant national research on various aspects of bullying (Espelage,

& Swearer, 2004), and although past research has intentionally spent time examining bullying in

specific populations, one population ignored in the research is the gifted student population

(Peterson & Ray, 2006a, 2006b). The limited research available indicates gifted students may be

vulnerable or are at risk of being targets of bullies, may become the bullies, or may even be bully-

victims (Cross, 2001a, 2001b; Peters & Bain, 2011; Parliament of Victoria, 2012; Roddick, 2011;

Schroeder-Davis, 2012). While educators and administrators play an integral role in the

development and safety of the gifted child, the research is clear; school counselors are best suited

to serve the unique developmental needs of gifted students (Bauman, 2008; Philips & Cornell,

2012).

The study was conducted to understand how versed and skilled counselors perceive their

abilities to be in addressing gifted and bullying at the elementary, middle school, and high school

levels. Data was collected through interviews of 9 Minnesota counselors who serve gifted

students, 3 at elementary, 3 at middle school and 3 at high school. Data showed bullying is a

concern at the elementary and middle school level. Gifted students were identified as a targeted

group at the elementary and middle school level. Most elementary and middle school counselors

did not feel confident in serving the unique social and emotional needs of gifted students. The

study found counselors did utilize numerous strategies to address bullying, more at the elementary

level with fewer utilized at the high school level. Most counselors in the study reported an anti-

bullying program is being utilized, with four counselors reporting no program being used.

Counselors overall perceive the strategies utilized by administrators were effective for reducing

bullying.

The themes of the dissertation include: the concept of giftedness, the unique social and

emotional needs of gifted students, the evolving role of the counselor in serving gifted students,

and the information about bullying and prevention and intervention.

The study contributes to the body of research on bullying by providing more information

for those who work toward understanding the healthy development of gifted youngsters. Also, the

study sheds light on preparedness of counseling programs at colleges and universities preparing

counselors to meet the unique needs of gifted students.

Keywords: Bully, Bullying, Social & Emotional, Counselors, Gifted, Prevention, Intervention

3

Dedication

This journey, and final paper is dedicated first and foremost to every child, of any age ever

bullied. To the bullied: Please know you are loved, valued, and not forgotten. My heart breaks for

all the students bullied who felt their best option was to take their own life. I am equally frustrated

to have discovered in this process adults have not always been there in ways which you needed.

The study seeks to advance this cause, and to build capacities in all those working with students,

but especially in school counselors.

Next, I dedicate this work to Leta Setter Hollingworth (1886-1939). I became obsessed

with Leta and what she accomplished for the gifted population. Why don’t more people know

about these accomplishments? One of the first counselors of gifted education, she devoted her life

to helping us further understand the social and emotional needs of the gifted. It was fascinating to

see that our paths crossed years apart in Chadron, McCook, and Lincoln, Nebraska. The fact so

much of what is being done even today comes from seeds Leta planted, adds to the legacy and

impact of her life.

I would feel remorse for not recognizing another researcher, Dr. Susan M. Swearer of

Nebraska. Dr. Swearer, at the University of Nebraska, either alone, or through collaborations with

others, has contributed endless amounts of research and ideas to the field. A well-respected

advocate nationally as well as internationally, she was a recent 2019 Keynote speaker at the

(second) World Anti-Bullying Forum held in Dublin, Ireland.

Jean Sunde Peterson has also become my modern-day professional obsession. What a

legacy she is leaving, not to mention what impact and contributions she is making to the field of

gifted and counseling. With that, I also direct everyone’s attention to the marvelous work of Linda

Silverman with the Gifted Development Center in Colorado. Then there’s Susannah H. Wood. It

4

is my hope to meet each of you yet in my lifetime. I know the solution for eradicating bullying

and keeping our children safe will have been highly influenced by your work and

recommendations.

Finally, I dedicate this to Dr. James T. Webb. I had the privilege of meeting and speaking

to Dr. Webb at a SENG facilitator training in Denver. Dr. Webb was a pioneer with his work

around the social and emotional needs of gifted students. Unfortunately, Dr. Webb passed away

on July 27, 2018, just as I had finished the draft of Chapter three of my dissertation. The SENG

organization will remain a critical organization for addressing the social and emotional needs of

gifted students today and in the future.

5

Acknowledgements

I begin by acknowledging my patient and incredible wife, Kandy, and amazing daughter,

Mariah, who have been nothing but supportive. This enormous project has meant weekends away

from home, piles of books always lying around my designated area, endless days of sitting at the

computer, days processing ideas aloud, days attending meetings with experts-- superintendents,

the MN Dept of Education, teachers, counselors and administrators, as I learned everything I

could about the themes of my dissertation.

I never would have gotten through the journey without my St. Cloud cohort. What a

wonderful, diverse and unique group of individuals coming from such varied backgrounds and

experiences. May great things continue for each of you with your completed degrees!

I am forever grateful for all the wisdom of people who have taken this path before me, and

who have moved the field forward so our gifted students are learning new information and skills

each day. A special thanks to gifted educators and authors, Dr. Richard Cash, and Barbara

Dullaghan for their knowledge and inspiration. This process has taught me that there is much

work and advocating to be done when it comes to meeting the social and emotional concerns of

students, especially our gifted population.

Thanks to my editor, Rita Speltz, a retired English teacher. I would not have chosen

anyone else. Those darn split infinitives needed extra attention.

Thanks to everyone who agreed to be a part of my board, including Dr. Elizabeth Fogarty

of the University of Minnesota, whom I will always be envious of, knowing she has studied with

the best of the best in Gifted education, including studies at the University of Connecticut.

It goes almost without saying, but a special thanks to all the counselors who agreed to

participate in the study, especially during a pandemic.

6

Finally, thanks to everyone who encouraged me, who asked me how I was progressing, or

who has ever been a part of my life, and added to the skills I needed to go through such a process

of completing and defending a dissertation. This would include my parents, Marvin and Beverly

Halley; my brother, Ron; my sister, Tammy; my friend, Meredith Aby-Keirstead, and my high

school speech teacher, Patricia (Olson) Stauss of Lincoln, Nebraska. Ms. Stauss has given me

skills which have allowed me to be a part of conversations in places I never dreamed possible,

including a symposium at Harvard.

7

Table of Contents

Page

List of Tables ............................................................................................................... 12

Chapter

I. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 13

Statement of the Problem ............................................................................. 20

Purpose of the Study ..................................................................................... 21

Assumptions of the Study ............................................................................. 21

Research Plan for the Study ............................................................................... 22

Delimitations ................................................................................................ 22

Research Questions ...................................................................................... 23

Definition of Terms ...................................................................................... 24

Summary ............................................................................................................ 29

II. Review of Related Literature ................................................................................... 32

Understanding the Conceptualization of Giftedness .......................................... 33

History of the Concept of Giftedness ........................................................... 35

Other Relevant Conceptions of Giftedness .................................................. 40

Conclusion .................................................................................................... 44

The Unique Social and Emotional Needs of Gifted Students ............................ 46

Common Traits of Gifted Students .............................................................. 49

Socialization: Peer Relationships and Possible Isolation ............................. 50

Overexcitabilities of the Gifted Child .......................................................... 51

Depression and Suicide ................................................................................ 54

8

Chapter Page

Social and Emotional Competence: Focus on The Whole Child ................. 57

Conclusion .................................................................................................... 57

History and Changing Role of the Counselor in U.S. Schools ........................... 59

Industrial Revolution .................................................................................... 60

The Beginning of Counseling Gifted Students ............................................. 61

The Great Depression ................................................................................... 61

Formation of American School Counselor Association (ASCA) ................ 66

A Nation at Risk ........................................................................................... 69

Limitations and Concerns ............................................................................. 70

History of Bullying ............................................................................................. 74

Types of Bullying ......................................................................................... 77

The Bystander: Hurting or Helping .............................................................. 79

History of Bullying in Minnesota ................................................................. 79

Teachers and Bullying .................................................................................. 82

Administrators and Bullying ........................................................................ 84

Counselors and Bullying .............................................................................. 85

Characteristics of a Bully ............................................................................. 85

Characteristics of a Victim ........................................................................... 86

Prevalence and Significant Concern ............................................................. 87

Counselors, Gifted and Bullying .................................................................. 95

Significant Research on Gifted, Bullying, and Development ...................... 95

Gifted Students and Cyberbullying .............................................................. 98

9

Chapter Page

Effective Anti-bullying Strategies to Be Implemented and Supported by

Counselors ............................................................................................ 101

Effective Bullying Programs .............................................................................. 105

Conclusion of Literature Review ....................................................................... 109

III. Methodology ............................................................................................................ 113

Research Questions ...................................................................................... 114

Participants ......................................................................................................... 114

Human Subject Approval ................................................................................... 116

Research Design ................................................................................................. 116

Pilot Testing ................................................................................................. 116

Interview Questions ...................................................................................... 117

Instruments for Data Collection and Analysis ................................................... 119

Treatment of Data ............................................................................................... 119

Description of the Sample .................................................................................. 121

Procedures and Timelines .................................................................................. 124

Summary ............................................................................................................ 125

IV. Findings and Results ................................................................................................ 127

Introduction .................................................................................................. 127

Research Problem ............................................................................................... 127

Purpose of the Study ..................................................................................... 127

Interview and Participants ............................................................................ 128

Description of the Sample Participants .............................................................. 128

10

Chapter Page

Research Questions ............................................................................................ 131

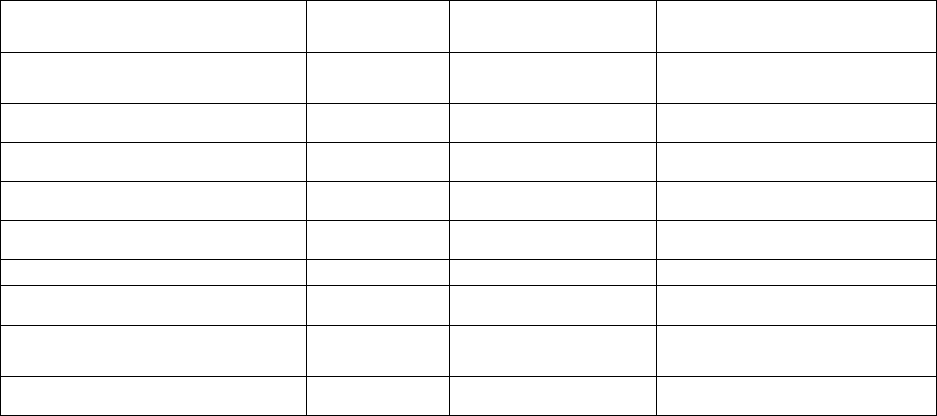

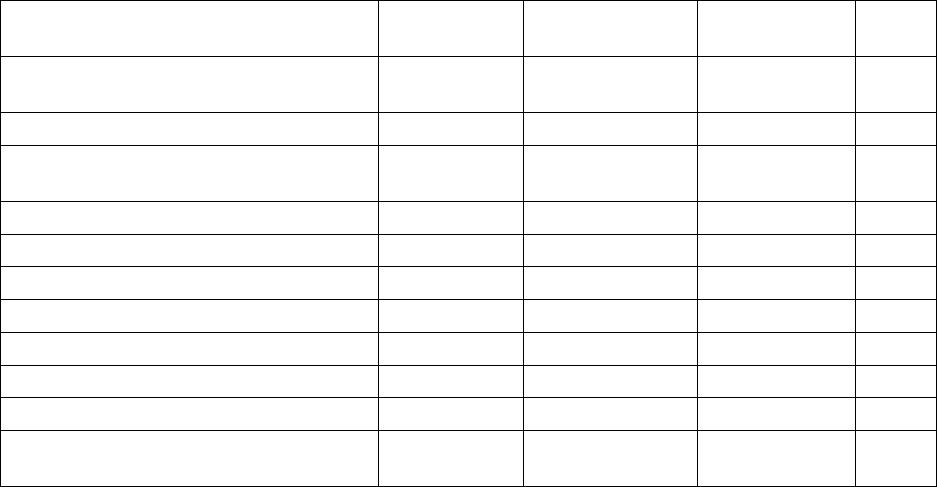

Interview Results: Participant Demographics .............................................. 132

Interview Results: Research Question One .................................................. 134

Interview Results: Research Question Two ................................................. 140

Interview Results: Research Question Three ............................................... 144

Interview Results: Research Question Four ................................................. 150

Summary ............................................................................................................ 154

V. Summary and Discussion ......................................................................................... 157

Research Questions ...................................................................................... 158

Research Findings Question One ................................................................. 159

Research Findings Question Two ................................................................. 164

Research Findings Question Three ............................................................... 165

Research Findings Question Four ................................................................ 170

Limitations .................................................................................................... 171

Addressing Themes Found in the Interviews ..................................................... 171

Recommendations for Furth Research ............................................................... 174

Recommendations for Practice ........................................................................... 175

Concluding Remarks .......................................................................................... 175

References ............................................................................................................................ 177

Appendices

A. Letter of Cooperation .................................................................................................. 256

B. Adult Informed Consent Form .................................................................................... 257

11

Chapter Page

Appendices (continued)

C. Qualitative Interview Questions ................................................................................. 259

D. Example of Coding Journal for Theme Analysis ...................................................... 261

12

List of Tables

Table Page

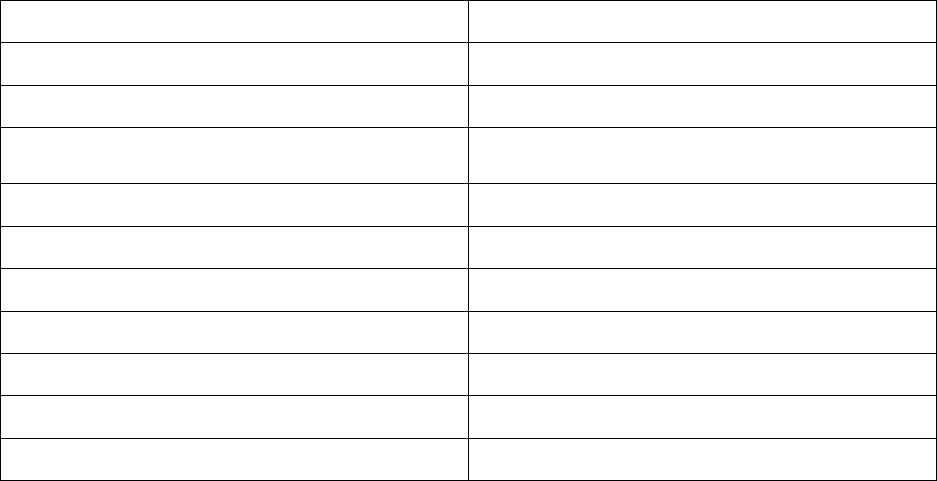

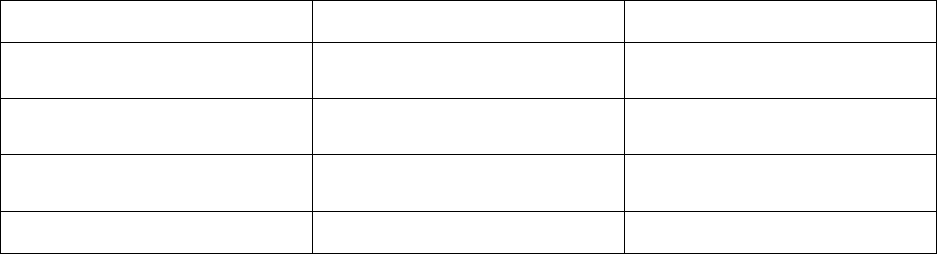

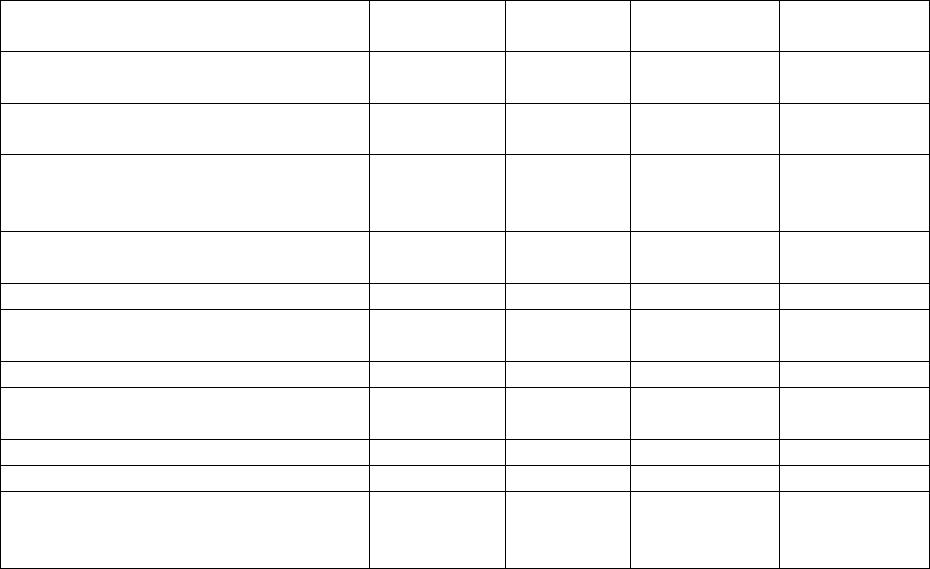

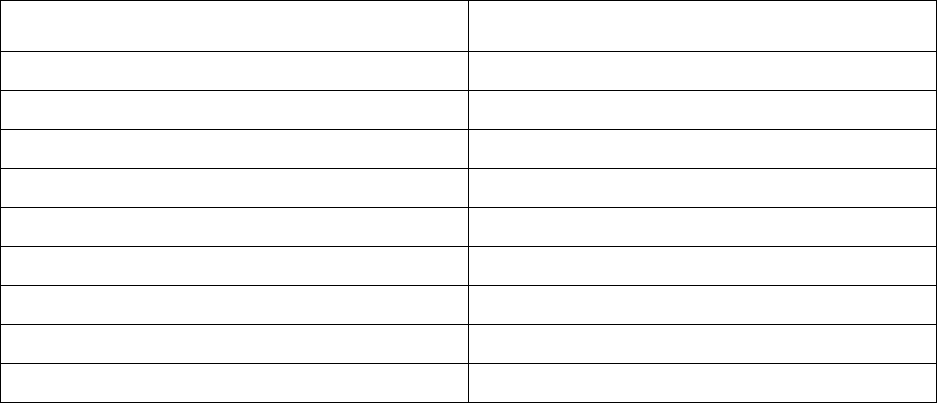

4.1 Respondents’ Years of Experience ........................................................................... 132

4.2 Respondents’ Area of Service .................................................................................. 133

4.3 Respondents’ Identified Race ................................................................................... 133

4.4 Counselors’ Perceptions of Occurrence of Bullying in their Building .................... 134

4.5 Counselors’ Perceptions of Targets of Bullying ...................................................... 138

4.6 Counselors’ Level of Confidence in Serving the Unique Needs of Gifted

Students .............................................................................................................. 141

4.7 Perception of Anti-Bullying Programs ..................................................................... 144

4.8 Counselors’ Perceived Strategies Used to Reduce Bullying .................................... 147

4.9 Strategies used by Administrators to Reduce Bullying ............................................ 150

4.10 Counselors’ Perceptions of Effectiveness of Strategies Used by

Administrators .................................................................................................... 152

13

Chapter I: Introduction

Dylan Klebold was identified as a gifted student. In fact, according to his mother’s

memoir Dylan, at age 4, through the school’s early entrance process, started kindergarten

(Klebold, 2016). The memoir reveals he struggled with the gifted program. Just 13 years later, on

April 20, 1999, Dylan Klebold, along with Eric Harris, murdered twelve students, one teacher,

and injured 24 others in Littleton, Colorado, before committing suicide in the Columbine

Shooting, one of several high-profile school massacres in the United States (Allanson, Lestor, &

Notar, 2015; Brown, & Merritt, 2002; Cullen, 2009; Hughes, 1999; Kohut, 2000; Langman, 2010;

Larkin, 2009; Viadero, 2009). Evidence suggests the shooters had planned and executed the

complex attack as a result of years of bullying (Leary, Kowalski, Smith, & Phillips, 2003). The

shooting involved Robyn Anderson, another gifted (honor) student who purchased two shotguns

and a Hi-Point 9 mm Carbine which would later be used in the shooting (Congressional Record,

2000).

Bullying had already been a significant concern internationally. Bullying had been the

focus of research in Scandinavia countries in the late 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, prior to the

Columbine Shooting (Devoe et al., 2004; Haynie, Nansel, Eitel, Crump et al., 2001; Olweus,

1993a. 1993b. 1996, 1999; O’Moore & Hillery, 1989; Rigby, 1993; Swearer & Cary, 2003;

Unnever & Cornell, 2003). By the 1990s, systematic research on student bullying was being

conducted in Scandinavia, Japan, England, Australia and Canada (Besag, 1989; Devoe et al.,

2004; Haynie et al., 2001; Olweus, 1993a, 1993b; Swearer, 2010; Swearer & Cary, 2003;

Unnever & Cornell, 2003, 2004).

14

However, while studies were being conducted on subpopulations, research specifically on

the gifted population was being ignored. Gifted children are a diverse group and may not fit the

historic profile. According to Colangelo and Wood (2015),

Gifted students live in poverty in both urban and rural areas (Howley & Howley, 2012;

Worrell & Young, 2012). Gifted students include Native Americans, Asian Americans,

African Americans, Latinos and other individuals from various racial and ethnic

backgrounds (Kitano, 2012). Gifted students can identify as gay, lesbian, queer, or

transgender (Peterson & Rischar, 2000). Students may have disabilities, may struggle with

underachievement, and may have difficulties with relationships. (p. 133)

Defining giftedness is problematic as there are several paradigms to consider (Kaufman,

2018). Levy and Plucker (2008) advocated for gifted students to be considered a separate and

unique population to gather much needed information for best serving their academic as well as

social and emotional needs.

As a result of the Columbine shooting in the United States, Dan Olweus began to train and

collaborate with his American colleagues in using systematic programming and research (Buck,

2017; Olweus, 1993a, 1993b). Olweus is considered the founding father of anti-bullying research.

He composed anti-bullying legislation in Sweden in the mid-1990s (Olweus, 1993a, 1993b).

Sweden’s legislation may have helped guide anti-bullying legislation in U.S. states beginning in

the late ‘90s. However, not until 2005 did the federal government collect data on bullying in the

United States. The study conducted by the U.S. Department of Education revealed nearly 28% of

students reported being bullied. Today, all states have some form of anti-bullying laws.

Minnesota’s first anti-bullying legislation (2009) ranked as one of the weakest in the nation by a

report released by the U.S. Department of Education (Weber, 2011). However, Minnesota

15

Governor Mark Dayton signed a tougher and more comprehensive bill in 2014 (U.S. Departent of

Education, 2011, 2014). Today, bullying is not taken lightly (Goldman, 2012; Kowalski, Limber,

& Agaston, 2012; Olweus, 2013a, 2013b). Students and adults have been reprimanded, and in

some cases sentenced for their involvement in bullying (Agaston, 2012).

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (2016), students are bullied for

numerous reasons. Gifted students have unique social and emotional needs, including

asynchronous development, intensities or Dabrowski’s overexcitabilities, and tendencies to

struggle with relationships (Alsop, 2003, Fonesca, 2011; Lind, 2001; Silverman, 1999). Gifted

students may experience anxieties, perfectionism, and a strong sense of justice (Adderholt-Elliot,

1989; Fonesca, 2011; NAGC, 2020). The gifted may even struggle to understand why someone

would bully another person, making them even vulnerable to bullying (Betts, 1985, 1986; Betts &

Kirher, 1999; Cross, 2001a, 1002b; Kitano, 1990; Peterson, & Ray, 2006a, 2006b). Other reasons

students are bullied include: Physical appearance, race/ethnicity, gender, religion, personal

beliefs, sexual orientation, health, and disabilities (Peterson, & Ray, 2006a, 2996b). As a result of

systematic research, and changes in U.S. laws around bullying, school counselors began to play

an important role in reducing bullying in schools (Phillips, & Cornell, 2012). Evidence from

several studies suggests shortage of teachers’ effectiveness when teachers address incidents of

bullying (Fekkes, Pijpers, & Verloove-Vanhorick, 2004; Lee, 2006; Mishna, Pepler, & Wiener,

2006; Thomsen, 2002, 2012). Philips and Cornell (2012) found school counselors are more

qualified than other educators to identify and confirm acts of bullying. Jacobsen and Bauman

(2007) argued school counselors displayed more empathy for victims of physical and relational

bullying than teachers. Counselors understand the impacts of bullying are far-reaching (Jacobsen

& Bauman, 2007). Counselors understand bullied gifted students report lower self-esteem and

16

self-worth (Austin & Joseph, 1996; Kokkinos & Panayiotou, 2004; Rigby & Slee, 1993). Gifted

students may encounter sleep disorders or illness (Gruber & Finneran, 2007; Kliewer, 2006;

Rigby, 1993, 1996, 1999, 2003; Vaillancourt et al., 2008) may have difficulties with relationships

(Boulton & Underwood, 1992; Edwards, Hershberger, Russell, & Market, 2001; Espelage & Holt,

2013; Gonsalkorale & Williams, 2007; Graham & Juvonen,1998; Juvonen, Nishina & Graham,

2000; Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996), may experience more anxiety and depression

as a result (Espelage & Holt, 2013; Graham, & Juvonen, 1998; Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpela, M,

Martunnin, Rimpela, A, & Rantanen, 1999; Kim, Koh, & Leventhal, 2005) and may have altered

brain functioning (Knack, Gomez, & Jensen-Campbell, 2010). Bullied children fantasize about

killing themselves more than non-bullied children and even attempt to take their life more often

than their non-victimized peers (Brunstein-Klomek, Marocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld, & Gould,

2007; Brunstein-Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfield, & Gould, 2008).

Significant findings of specific populations over the years caution certain populations may

be more vulnerable to bullying. Maker (1977) estimates 3% of all special education students are

gifted. Numerous studies conclude special education students are at a high risk of being targets

for bullying (Blake, Lund, Zhou, Kwok, & Benz, 2012; Swearer, Wang, Maag, Siebecker, &

Frerichs, 2012). Swearer et al. (2012) followed more than 800 special education and general

education students from nine elementary, middle, and high schools. The results revealed 77% of

the special education students were found to have been victimized by bullies, and 38% admitted

they had bullied others.

Another targeted group is the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transsexual population. Gifted

students are of various sexual orientations. For this reason, earlier research around LBGT and

17

bullying must be considered (NAGC, 1998). Concerns for gifted gay students initiated the

National Association for Gifted Children (1998) to establish a Gifted Children, Gay, Lesbian,

Bisexual and Transgender task force (NAGC, 1998). Data indicates there is still reason to be

concerned. A recent school climate survey (2009) found 61.1% of LGBT students felt unsafe at

school because of their sexual orientation, 39.9% felt unsafe because of their gender expression

(GLSEN, 2009, 2013).

Levy and Plucker (2008) advocate for making gifted students a special population. Levy

and Plucker (2008) argue,

Gifted students should be considered a special population because of differential abilities

and expectation, associated with their abilities. Gifted children constitute a unique

subculture that necessitates understanding and application of specialized skills by

understanding and application of specialized skills by helping professionals, including

school counselors. (p. 4)

One of the most, if not the most significant studies of gifted students at this time,

conducted by Peterson and Ray (2006a, 2006b), found 67% of gifted students had experienced

bullying by eighth grade. The study revealed bullying reported by 1 in 4 elementary gifted

students. Furthermore, 16% of gifted students identified themselves as bullies, with 29%

acknowledging they had violent thoughts. Peterson (2006) noted, “while most of the bullying

reported was verbal, it doesn’t mean it was any less harmful than the physical variety” (p. 165).

The limited research available recognized many gifted students do not feel comfortable sharing

their concerns with their families or teachers. The gifted population does not appear to want to

call any additional attention to their victimization (Peterson, & Ray, 2006a, 2006b).

18

Within the study of the gifted population, limited research on bullying of twice-

exceptional students is available (Baum & Owen, 1984: Rose, Monda-Amaya, & Espelage, 2009,

2011; Rowley, 2012). Twice exceptional is a term used for a student identified as gifted but also

has a learning disability. Twice exceptional identification often includes students on the autism

spectrum disorder (Winebrenner, 1996). Literature may also use the term 2E to describe these

students. Unfortunately, students with such specific learning disabilities face high levels of

bullying victimization (Elkind, 1973, Rose et al., 2011; Rowley, 2012). The National Center for

Learning Disabilities (2014) found 75% of students with disabilities report being bullied at least

once in the past 10 months. The fact bullying is happening in this population at such high rates

may be significant when considering it is difficult to diagnose giftedness. (Beckmann, &

Minnaert, 2018; Webb et al., 2005).

Bullying in the gifted population is an overlooked concern (Cross, 2001a, 2001b; Peterson

& Ray, 2006a, 2006b; Pfeiffer & Stocking 2000; Schroeder-Davis, 2012). Yet, this is not the first

time the gifted have been neglected (Eckel, 1950). Dr. Ruth Strang and Pauline Williamson began

the American Association for Gifted Children (AAGC) after noting the gifted were “the most

neglected children in our democracy” (AAGC, 1999, para. 1, Jolly, 2018). In a report to

Congress, Commissioner of Education, Sidney P. Marland, Jr. (1972), argued the most neglected

minority in American education was a group of youngsters he identified as gifted. If this is still

true today, this would account to over 3.2 million students in public schools in gifted and talented

programs, according to the latest report from the Office of Civil Rights within the U.S.

Department of Education. identified as gifted.

To present the other side, Mulvey and Cauffman (2001) caution, “...efforts to predict

which students will behave violently will not be successful” (p. 304). Espelage and King (2018)

19

leading bullying researchers point out Peterson and Ray’s (2006a, 2006b) study lacked a control

group. Neihart (1999) would argue gifted students have normal, if not better than average social

and emotional development. Dr. Tracy Cross has spent much time on this subject. Cross (2005)

has an important warning,

Gifted students need adults to guide them. Acts of individuals must be understood at the

individual level. The lesson of Columbine is not that gifted children are homicidal. Their

giftedness should in no way be assumed a cause agent in their appropriate act. A lesson of

Columbine should be school must create safe environments where learning can thrive.

Being gifted in differing types of school settings has led to different experiences. Rather

than finding condemnations for gifted students. We must commit ourselves to helping

students thrive, including gifted students. (p. 199)

In review, and to connect our themes of this complex topic and discussion, research on

bullying has been occurring in our country for over forty years (Espelage, & Swearer, 2004). The

actions of the (gifted) Columbine student shooters initiated the immediate need for research on

bullying in the United States. However, much needed research specifically on the gifted

population has been neglected and limited.

Since Columbine, each state has passed anti-bullying legislation, including Minnesota.

Despite this legislation, millions of students will be bullied this year (Modecki, Michin,

Harbaugh, Guerra, & Runions, 2014). Modecki et al., (2014) meta-analysis of 80 studies on

bullying involvement rates established bullying varies across studies from 9 to 98% of

participants. Overall, the meta-analysis revealed 35% of students will experience traditional

bullying and 15% will experience cyberbullying. Over 160,000 students, including gifted

students, will skip school because they are fearful of being bullied (Whitted and Dupper, 2005).

20

The 40 years of research reveals students from specific populations may be at a higher risk of

being bullied which includes special ed, LBGT, gifted, and 2 E students. Students of color, in

ELL, may also be marginalized for being different (Kohut, 2007; Sue, 2010).

Eradicating bullying requires us to take immediate action (Bullying Prevention, 2012;

Chamberlain, 2003). Experts agree school personnel, from educators, to administrators, to

counselors, must be involved in finding a solution (Espelage, & Swearer, 2004, 2010). Research

indicates principals or school leaders do not utilize all options available to implement and best

address school violence (Volokh & Snell, 1998). Further research reveals teachers are not trained

in knowing all the needs of gifted students (Rogers,1986, 2001; Smith & Shu, 2000), in knowing

all the programming options for bullying and gifted students, and are not trusted by gifted

students for having the capacity for best addressing their bullying concerns (Harris & Petrie,

2003). The key to fixing this problem lies in the hands of school counselors for numerous reasons

(Bauman, 2008; Philips & Cornell, 2012). School counselors are the key stakeholders in the

bullying intervention and prevention process (Austin, Reynolds, & Barnes, 2012). They are the

best suited to provide counseling, prevention and intervention to students in the educational

setting (Bardwell, 2010; DiMatteo, 2012; Harris, & Petrie, 2003; Philips & Cornell, 2012).

Statement of the Problem

Bullying is an important public health concern (Espelage, 2014, 2015; Espelage &

Swearer, 2004, 2010; Marr & Fields, 2001; Srabstein & Leventhal, 2010). Limited research exists

on gifted and bullying. Gifted students may be given to being targets of bullying for several

reasons (Blackburn, & Erickson, 1986; Boardman, & Hildreth, 1948; Cultross, 1982; Espelage,

2003; Espelage & Swearer, 2003, 2004; Garbarino & DeLara, 2003; Newman, Horne, &

Bartolomucci, 2000; Orpinas & Horne, 2006; Swearer, 2010; Swearer & Doll, 2001). Counselors

21

play a critical role in stopping bullying (Cross, 2001a, 2001b, 2005; Harris, & Petrie, 2003;

Olweus, 1993a 1993b; Ross, 1996; Silverman 1989, 1993; Smith & Sharp, 1994; Sullivan, 2000).

One population ignored in the 40 years of research on bullying is the gifted population. Use of a

qualitative study utilizing interviews allows for a deep, insightful analysis of what counselors

perceive around the seriousness of bullying, including the targeted populations, the strategies

utilized, anti-bullying programs used, as well as effectiveness of strategies by their administrators

for reducing bullying.

Purpose of the Study

The study investigated the perceptions of Minnesota elementary counselors, middle school

counselors, and high school counselors, in various districts working with identified gifted

students. The purpose was to determine if participating counselors felt skilled in adequately

supporting the unique social and emotional needs of gifted students, specifically around bullying.

The study examined the bullying strategies and anti-bullying bullying programming being utilized

to support gifted learners. To conclude, perceptions of counselor's feelings regarding

administrators use of strategies for reducing bullying were examined. Information was

systematically gathered and analyzed to provide possible explanations regarding counselors’

perspectives on bullying and the gifted population.

Assumptions of the Study

Roberts (2010) defined assumptions as the aspects of the study one might “take for

granted” (p. 139). The following assumptions were identified in conducting this quantitative

design study:

• Study participants answered the questions honestly and without reservation.

22

• The sample studied was representative of the total population of Minnesota’s

practicing school counselors.

• Participants had access to or knew who the gifted students are currently served.

• Study participants understood their district’s bullying policies.

• Study participants understood the definition of bullying as used by the Minnesota

Department of Education Safe and Technical Schools.

Research Plan for the Study

Following approval by the dissertation committee, the researcher completed the following

• Received approval from St. Cloud State University’s Institutional Review Board

(IRB).

• Developed and sent informational and recruitment message describing the purpose of

the study, the informed consent provision, and provided the researcher’s information if

there were any concerns or questions.

• Contacted numerous principals throughout the state of Minnesota, kindergarten to

grade 12, to seek permission to consider their counselors who worked with gifted

students for participation in the study.

• Developed a set of questions for a 30-minute interview in which participants could

express interest to participate.

• Conducted thirty-minute interviews with each participant.

Delimitations

Roberts (2010) described de-limitations as the researcher’s method of narrowing the

study’s scope. The delimitations of this study include:

23

• The researcher chose the time of the year in which the study was conducted. A hurdle

faced when collecting qualitative data was a pandemic occurred reducing personal

access to counselors from across the state, resulting in all interviews being completed

virtually.

• The state of MN does require that all districts have an identification in place to

determine who the gifted students are. The legislation, however, does not require

districts to provide services for gifted students. For the sake of this study, counselors

were selected where services are being provided to gifted individuals.

Schwandt, (2007) describes a “crisis of representation” as the difficulty to capture and

convey an experience of another individual simply using words. Several tools were employed to

help maximize effect of the interviews. Member checks were utilized to cross-check the

researcher’s interpretation of interviews with the meaning of the interviewee in order to preserve

her voice as it relates to the phenomenon of the study. Piloting of questions was utilized as well as

numerous reviews of the coding and data gathered.

Research Questions

The study was qualitative in nature. The researcher interviewed counselors serving gifted

students from elementary, middle school and high schools across the state of Minnesota. The

following research questions were used to guide this study.

1. To what extent do school counselors believe bullying occurred in their building(s), and

what specific populations, if any, do counselors identify as targets of bullying?

2. What is the level of confidence of school counselors in understanding and serving the

unique social and emotional needs of gifted students?

24

3. What strategies and anti-bullying programs do school counselors utilize while

addressing bullying of gifted students?

4. What strategies do counselors identify to be most often used by administrators for

creating a safe school environment for all students, including the gifted population,

and do counselors perceive these strategies to be effective?

Definition of Terms

Aggression. Behavior intended to harm another individual who does not wish to be

harmed. (Baron & Richardson, 1994).

Anti-bullying. Anti-bullying refers to laws, policies, organizations, and movements

aimed at stopping or preventing bullying (Olweus, 1993a, 1993b).

Bullies. People who exert dominance over or inflict pain upon others through physical,

verbal, sexual, or emotional abuse. They appear to derive satisfaction from inflicting injury and

suffering on others (Olweus, 1993a, 1993b).

Bullying. A person who is exposed, repeatedly and over time to negative actions on the

part of one or more persons, and he or she is having difficulty defending himself or herself.

Although the definition may vary by state, a common definition includes:

1. Unwanted, negative active actions or aggression.

2. Repetition: Bullying behavior has been repeated over time.

1. Imbalance of Power: Bullying often involves an imbalance of power or strength

(Olweus, 1993a , 1993b, 1999).

Bullying. Bullying is any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of

youths who are not siblings or current dating partners which involves an observed or perceived

power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may

25

inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth including physical, psychological, social, or

educational harm (Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger, & Lumpkin, 2014).

Bullying: Minnesota Dept of Education Safe and Supportive Schools Act Definition.

Bullying is an act that is intimidating, threatening, abusive or harming conduct that is objectively

offensive and,

1. There is an actual or perceived imbalance of power.

2. The conduct is repeated or forms a pattern

3. Materially and substantially interferes with students' educational opportunities or

performance or ability to participate in school functions or activities or received school

benefits, services or privileges (“MDE”, Safe & Supportive Schools Act, 2019).

Bullying intervention. A schoolwide foundation that offers a value system based on

caring, respect, empathy, and personal responsibility. Using positive discipline and support,

having clear behavioral expectations and consequences, building capacities and skills, and

involving all stakeholders including students, parents, adults, teachers, counselors, psychologists

and administration. Intervention should target specific risk factors and teach students and parents

skills for identifying and addressing bullies (Feinberg, 2003; “NCSP”, 2003; Olweus, 1997, 2001,

2013).

Bullying prevention. A prevention plan includes practices and policies that address all

forms of bullying, harassment, violence and emphasize eliminating such behaviors. A

comprehensive plan should be timely, used consistently, include social-emotional support for

victims, bullies and bystanders, and must have clear disciplinary steps (National Association of

School Psychologist, 2018).

26

Bully-victim. Bully-victim is a child who is at times a bully, and yet at other times a

victim of a bully (Dewar, 2007).

Cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is bullying that takes place over digital devices like cell

phones, computers, and tablets. Cyberbullying can occur through SMS, Text, and apps, or online

in social media, forums, or gaming, where people can view, participate in, or share content.

Cyberbullying includes sending, posting, or sharing negative, harmful, false, or mean content

about someone else. It can include sharing personal or private information about someone else,

causing embarrassment or humiliation (Stopbullying.gov, 2014).

Definition of giftedness from Marland Report. Gifted and talented children are those

identified by professionally qualified persons who, by virtue of outstanding abilities are capable

of high performance. These are children who require differentiated educational programs and

services beyond those normally provided by the regular school program, in order to realize their

contribution to self and society. Children capable of high performance include those with

demonstrated achievement and/or potential ability in any of the following areas:

1. General intellectual ability

2. Specific academic ability

3. Creative or productive thinking

3. Leadership ability

4. Visual and performing arts

5. Psychomotor abilities (Marland, 1972).

Direct bullying. Direct bullying is a verbal and/or physical form of aggression. In fact,

this type of bullying may involve hitting, kicking, or making insults, offensive and hurtful

comments or even threats (Shetgiri, 2014).

27

Emotional bullying. A form of bullying that can be more subtle and can involve isolating

or excluding a child from activities. This type of bullying appears to be more common among

girls (Juvonen, Graham & Schuster, 2003).

Evidence-based approach. A practice that has been rigorously evaluated and has shown

to make a positive, statistically difference in important outcomes. Results should be producible in

other settings (Oregon Research Institute, 2020).

Exclusion: This is the act of excluding someone or somebody; the state of being left out,

especially from mainstream society and its advantage (Social Exclusion Unit, 2001).

Indirect bullying. This type of bullying often refers to relational aggression, which

includes social exclusion of victims through the manipulation of social relationships by bullies or

injuring the reputation of the victims. Relational bullying is more common among girls and can

lead to feelings of rejection at a critical time in social development (Shetgiri, 2014).

Non-verbal bullying. These are unwanted acts, such as threatening gestures, defacing

property, pushing or shoving, or even taking items from others (Atlas & Pepler, 1998).

Physical bullying: A type of bullying that can be physical in nature. This type of bullying

can accompany verbal bullying and involve acts such as kicking, hitting, biting, pinching, hair

pulling, and threats of physical harm (Janssen, Craig, Boyce, & Pichett, 2004).

Psychological bullying: This is a form of bullying that includes dirty looks, stalking,

manipulation, intimidation, and extortion (Olweus, 1993a, 1993b).

Perceptions. The study of human perception is complex. For the sake of this study

perception will be defined as understanding one’s reality from information obtained by senses,

intuition, knowledge, and experiences (Cantril, 1968).

28

Mass shooting. When someone “kills four or more people in a single incident (not

including himself), typically in a single location” (Krouse & Richardson, 2015).

MN Safe and Supportive Schools Act. An act relating to education; providing for safe

and supportive schools by prohibiting bullying; amending Minnesota Statutes 2012, section 124

D. 895, subdivision 1; 124D. 8955; Minnesota Statutes 2013 Supplement, section 124D.10,

subdivision 8 proposing coding for new law in Minnesota Statutes, chapters 121A; 127A;

repealing Minnesota Statutes 2012, section 121A.0695, (“MDE”, 2019).

School climate. The feelings students and staff have about their environment over time a

period of time (Peterson & Skiba, 2001).

School guidance counselor. Although the role of the counselor has evolved over time,

many counselors now focus on one of, or all three areas: Removing barriers to academic

achievement, supporting social and emotional development of students, and guiding college and

career readiness decisions (“ASCA”, 2001, 2003, 2008, 2012).

Social bullying. This type of bullying is often referred to as relational bullying or

relational aggression. Its purpose is to hurt someone’s reputation or relationships. This is done by

excluding individuals, leaving individuals out on purpose, spreading rumors about someone,

embarrassing someone on purpose, often in a public form, or telling other children not to be

friends with an individual (U.S. Department of Health, 2014).

Social withdrawal. Described as social inhibition, shyness, reticence, and social

isolation. These are all terms which conjure up images of an individual who spends time alone,

not interacting with others. Some of these terms may carry connotations of social anxiety,

isolation, insecurity, fearfulness, wariness, or loneliness. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and

shyness are often used interchangeably (Rubin, Hymel & Mills, 1989).

29

Thrice-exceptional (3e). A student who is colored, gifted and has a special academic or

behavioral need (Lawson-Davis, 2018).

Twice-exceptional (2e). Twice exceptional individuals demonstrate exceptional levels of

capacity, competence, commitment, or creativity in one or more domains coupled with one or

more learning difficulties. This combination of exceptionalities results in a unique set of

circumstances. Their exceptional potentialities may dominate, hiding their disability; each may

make the other so that neither is recognized or addressed (Baldwin, Omdal, & Pereles, 2015).

Twice-exceptional (2e). The term “twice-exceptional,” also referred to as “2e,” is used to

describe gifted children who have the characteristics of gifted students with the potential for high

achievement and give evidence of one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility

criteria. These disabilities may include specific learning disabilities, speech and language

disorders, emotional/behavioral disorders, physical disabilities, autism spectrum, or other

impairments, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. (“NAGC”, 2018).

Verbal bullying. A form of direct bullying. It is when an individual uses insults, teasing,

or harmful words to gain power over his or her peers (Olweus, 1993a, 1993b).

Victim. This is the individual being bullied, the person or group who receives the

aggression of the bully/bullies. (Olweus, 1993a, 1993b).

Youth violence, The term refers to the intentional use of physical force or power to

threaten or harm others, impacting young people between ages 10-24 (“CDC”, 2018).

Summary

Bullying is a significant public health concern in the United States, and the subject of an

ever-increasing body of research world-wide (Batsche, & Knoff, 1994; Bosworth, & Espelage,

1999; Coy, 2001; Espelage, & King, 2018; Espelage & Swearer, 2003). At age 87, Olweus was a

30

keynote speaker at the first World Bullying Forum held in Sweden in 2017. The second World

Bullying Forum was held in July of 2019 in Ireland, and included keynote speakers, researchers,

presenters and participants from over 37 countries, including participants from midwestern United

States. While there are many studies on elementary, middle and high schools nationally and

internationally (Ahmed & Braithwaite, 2004; Berdondini & Smith, 1996; Dake, Price &

Telljohann, 2003; Juvonen, Nishna, Graham, 2000), studies focusing specifically on gifted

students are limited. Bullying impacts the social and emotional needs of students as well as

impacts their academic needs and opportunities (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; Juvonen & Nishina,

2000; Milsom, & Gallo, 2006). Bullying has the potential to continue to impact students even

beyond their school experience (Leff, Power, & Goldstein, 2004; Marsh, Parada, Craven, &

Finger, 2004; Meraviglia, Becker, Rosenbluth, Sanchez, & Robertson, 2003; Paquette &

Underwood, 1999; Rigby, 1996, 2003; Van der Wal, de Wit, & Hirasing, 2003). Research

indicates the potential of bullying leading to rejection, feelings of isolation, exclusion, low self-

esteem, poor academic achievement, anxiety, depression, and may contribute to suicidal

tendencies (“CDC” 2015; Nansel, Haynie, & Simons-Morton, 2003). The gifted student

population may especially be vulnerable or at risk for being targets of bullies, or may become

bullies, or bully-victims themselves (Cross, 2001a, 2001b, Peterson & Ray, 2006a, 2006b;

Roddick, 2011Schroeder-Davis, 2012). Whitted and Dupper (2005) argue school counselors play

a pivotal role as program developers and promoters, as well as on-site coordinators of bullying

prevention programs. In addition, counselors play the key in helping gifted students to cope

effectively and navigate the challenges of being gifted and bullied (Nansel et al., 2003; Peterson,

2006; Wood, 2010).

31

Limited research exists on the perceptions of school counselors regarding bullying and

gifted students (Peterson, & Ray, 2006a, 2006b). Chapter I provided the argument for the study

by laying out the complexity of this problem, the purpose and significance of the study, the

statement of the problem, as well as the scope of the research questions. Chapter II presents a

literature review on the concept of giftedness, the unique social and emotional needs of gifted

students, and the evolving role of the school counselor in serving gifted students. The review will

end by examining the results of nearly 40 years of research on bullying, and evidence-based

practices counselors can utilize with prevention and intervention strategies and anti-bullying

programs in the counseling of gifted individuals. Chapter III describes the methodology for the

study, with Chapter IV analyzing the data, and Chapter V synthesizing these findings through

discussion, leading to recommendations, and evidence-based solutions used by counselors for

reducing bullying incidents and keeping all students, including gifted students, safe and well. The

study then concludes with a bibliography and appendices.

32

Chapter II: Review of Related Literature

Espelage and Swearer (2003) argue bullying has emerged as one of the most fundamental

problems facing schools to date. Despite this argument, Peterson (2006), believes counselor

training programs have given little attention to the gifted student population, especially meeting

the unique social and emotional needs of high-potential students, including twice-exceptional

students. Peterson (2006) asserts:

All children are affected adversely by bullying, but gifted children differ from various

other populations in significant ways. Bullying in the gifted-student population is a highly

significant and overlooked problem that leaves these students emotionally shattered,

making them even more prone to extreme anxiety, dangerous levels of depression and

sometimes even violence and self-harm. (p. 1)

To clearly explore and understand the complexity of this phenomenon, the literature

review will be divided into four themes. First, the literature review will examine popular theories

around the concept of Giftedness. Each state defines “Giftedness” in its own terms, and thus

provides services differently based on these definitions (NAGC, 2010). However, the study will

share a common definition (Marland, 1972) used by most states in determining their definition,

services, procedures and policies. Next, the literature review will examine the unique and specific

social and emotional concerns of gifted students. The study then will explore and define the

evolving role of counselors in working with gifted students. Finally, the literature review will

examine bullying, its impacts on students, including gifted students. The literature on the bully,

the victim, and the bystander will be discussed. This review culminates in understanding the

counselor’s role in serving students with prevention strategies and programming for reducing

bullying.

33

By breaking down this complex phenomenon into themes: the concept of giftedness,

specific social and emotional needs of the gifted, counselor’s evolving role in serving the gifted,

and, finally, ways in which counselors may support gifted students through strategies and

programming, the review may provide insights and information to be used and analyzed for

keeping gifted children and adolescents safe from suicide, self-harm, violent thoughts, threats,

intimidation, death by others or even from devastating violence (Baker, 1995; Bartel, & Reynolds,

1986; Peterson & Ray, 2006a, 2006b).

Understanding the Conceptualization of Giftedness

Even after an extensive review of literature on the subject, a definition of “Giftedness” or

assigning of the label of “gifted remains elusive (Bristow, Craig, Hallock, & Laycock, 1951, Card

& Guiliano, 2016). Abeysekera’s (2014) research illuminates the change of definitions of

giftedness over the past centuries is due to social, scientific, and political reasons, including the

development of intelligence testing, and the U. S. Department of Education’s initiative to identify

talented youth among minority students. Researchers Al-Hroub and Khory (2018) elucidate the

abundance of diverse definitions of giftedness is and has been a major problem in the field of

gifted research. Miller (2008) would agree. Miller believes a clear definition of giftedness is

needed in order to successfully teach, parent, and counsel, and even effectively study and

understand giftedness.

Coleman and Cross (2001) provide the history and rationale for defining giftedness in

their collective text, taking the reader back to Ancient Greece, then to Emperor Charlemagne in

eighth-century France, then brings the reader to the United States and our founding fathers.

According to Coleman and Cross (2001), Thomas Jefferson proposed tests be instituted to

identify gifted learners at the public’s expense (p. 2). Jefferson said, “We hope to avail the state of

34

these talents which nature has sown as liberally among the poor as the rich, but which perish

without use, if not sought for and activated” (Coleman & Cross, 2001, p. 43). Jefferson’s line of

reasoning has persisted. Gifted expert and researcher, Joseph Renzulli, claims the concept of

giftedness may be the most controversial topics in the field of gifted education. Renzulli’s 1978

article, What makes giftedness? Re-examining a definition is considered one of the most read and

cited articles in gifted research. According to Renzulli, finding and agreeing on a definition is

difficult for at least two reasons (Renzulli, 1978). The first is the definition can limit or restrict the

number of performance areas considered in determining the eligibility for special programs. A

conservative definition might limit a student from entering a gifted program purely because the

program might consider academic performance only and exclude other areas such as art, music,

leadership, drama, public speaking and creative writing (Al-Hroub, & Khoury, 2018; Renzulli,

1976, 1978, 1986, 1997a, 1997b, 1998, 2000). The second reason provided by Renzulli is finding

and agreeing on a definition may specify the degree or level of excellence a child must obtain to

be considered gifted (Renzulli, 1978, 2000).

The National Association for Gifted Students position paper, Key Considerations in

Identifying and Supporting Gifted and Talented Learners, found on the NAGC (2020) site claims:

“Definitions provide the framework for gifted education programs and services, and guide key

decisions such as which students will qualify for services, the areas of giftedness to be addressed

in programming (e.g., intellectual giftedness generally, specific abilities in math), when the

services will be offered, and even why they will be offered.” Rogers (2001) cautions gifted

students needing to be carefully placed in programs best fitting for their needs. Defining

giftedness is complex for several reasons, including the lens educators, counselors, parents or

scholars view giftedness or the various paradigms from the 1800s that exist until today.

35

History of the Concept of Giftedness

Beginning in 1884, Francis Galton, a pioneer in the study of human intelligence, set to

work in a laboratory in London. He began testing different mental abilities (Al-Hroub & Khoury,

2018). Galton, often referred to as the “Father” of gifted education, believed children could inherit

the potential to become gifted adults like their biological parents (Gallagher, 1994; Galton, 1869,

1892; Tannenbaum, 1983). Galton was the first to use the terms “Fixed intelligence” which means

a person is born with a pre-determined ability to think or process ideas and information (Al-Hroub

& Khoury, 2018). This view is rejected today Dweck (1986, 2006) as more evidence indicates

intelligence is malleable (Jacobs, 2015). Terman’s initial studies were printed in Hereditary

Genius in 1892 (Gallagher, 1994; Tannenbaum, 1983).

In 1905, the Binet-Simon intelligence scale was developed, to be used to help identify

slow or handicapped students (Aubrey, 1977). The Binet-Simon scale became the first practical

intelligence scale applied to identify differences in school settings. The Binet-Simon test was

translated into English by Henry Goddard. The test was then revised by Lewis M. Terman at

Stanford University and subsequently became known as the Stanford-Binet in 1916 (Al-Hroub &

Khoury 2018; Colangelo & Davis, 1997, 2003; Davis & Rimm, 1998; Delisle, 1992; Jolly, 2004).

The test used the concept of mental quotient, which was determined by dividing a person’s mental

age by his chronological age. The term was then renamed intelligence quotient, or IQ (Al-Hroub

& Khoury, 2018; Sattler, 2001). Unlike Binet, Terman was interested in looking at the cognitive

abilities of students at the higher end of the intelligence scale. Gifted students were defined by

Terman as those students with an IQ at or above 140 on the intelligence scale and who scored in

the top one percent (Colangelo & Davis, 1997; St. Clair, 1989) which is lower than the 3-5% of

identification measures often used today. With the introduction of intelligence testing,

36

“giftedness” could now be quantified, operationalized and addressed within America’s schools

(Al-Hroub & Khoury, 2018; Jolly, 2004). Terman conducted one of the first longitudinal studies

of gifted children and published in five volumes of Genetic Studies of Genius (Burks, Jensen,

Terman, 1930; Cox, 1926; Terman, 1925; Terman & Oden 1947, 1959).

In 1926, Leta Setter Hollingworth, at times referred to as the “Mother” of Gifted

Education (Gladding, 1984), published her book, Gifted Children, Their Nature and Nurture

(Hollingworth, 1926). She is also considered the first counselor to the gifted. Hollingworth

proposed her own definition of giftedness, which included setting the bar at a 180 IQ for

profoundly gifted students. There is reason to believe the term “gifted” has been universally used

ever since to refer to children born with high intelligence (Myers, & Pace, 1986). Today gifted

students may also be referred to as gifted and talented, high-achieving, highly talented, above-

average, genius, phenoms, polymaths, student wonders, student sensations, poppies, or high

potential in research or literature reviews (Feldman, 1999; Feldman & Fowler, 1998; Gagne,

1998, 1999; Gross, 1998; Morelock, 1996; Simonton, 1992, 1994; Vygotsky, 1962, 1978).

Various scholars in the field of education over the years have attempted to define different aspects

of giftedness (Kaufman, 2018) helping to expand the conceptualization of giftedness (NAGC,

2019). Kaufman himself was misdiagnosed and incorrectly placed in a special education class.

Kaufman spent years looking across the hall at students in a gifted classroom (Kaufman, 2018).

Sternberg. Robert Sternberg’s theory, most mentioned in the review of definitions, is

known as the Triarchic Theory of Human Intelligence. Sternberg is said to have had negative

experiences with the traditional IQ measurements (Sternberg, 1984). Sternberg’s theory

comprises three different types of thinking which include: analytical, creative, and practical

(Sternberg, 2003a, 2003b). Sternberg argues a person having higher intelligence in one or more of

37

these areas would be more successful (Sternberg, 2003a, 2003b). Through metacognition the

individual would need to determine which mode of thinking would be the most appropriate.

Sternberg acknowledges people may differ in their general ability to use the three types of

thinking (Sternberg, 1984). To understand intelligence, Sternberg argues experts must consider

the abilities a culture values (contextual subtheory), the degree of novelty of the task (experiential

subtheory), and the cognitive process necessary to solve a task (componential subtheory)

(Kaufman, 2018). More recently Sternberg transformed his triarchic theory into the “Theory of

Successful Intelligence.” Sternberg argues all three forms of intelligence are important for

achieving one’s goal in life (Kaufman, 2018). Sternberg clearly plays a significant part in the

history of defining giftedness; however, his models were not as widely applied or accepted as

other theorists (Kohlberg, 1964, 1969, 1984; Kohlberg & Diessner, 1991; Sternberg, 2010; Turiel,

1979, 1983, 2002). Sternberg’s theory focuses not just on the abilities of the gifted, but on

conceptual processes, the ways the gifted think separates these individuals from other nongifted

students or other populations (Kaufman, 2018; Sternberg & Grigorenko, 1993).

Renzulli. Joseph Renzulli’s approach is known as the Three Ring Conception of

Giftedness (Renzulli, 1976). Unlike Sternberg’s theory, the Renzulli model (1998) has been

successfully used in schools around the world since its inception. The Three-Ring model consists

of three basic clusters of human traits which include: above average ability, a high level of task

commitment, and a high level of creativity (Renzulli, 1976, 1998). Renzulli’s model was

developed by studying adults who were highly successful or demonstrated exceptional

achievement. Renzulli (1978, 1997a, 1997b, 1998) views giftedness more as a behavior than an

attribute. The Three Ring Concept or approach has found support amongst educators, as the

conception allows students to be identified and not with an IQ alone. As a result of this theory,

38

more diverse students have been identified (Renzulli, 1986, 2000). However, Renzulli’s model

may fall short when a student does have a high ability or high IQ, and is considered gifted or

profoundly gifted, but still fails to perform and fails to excel. Renzulli may argue their task

commitment has not been exposed to stimuli needed for motivation (Renzulli, 1976, 1988, 1998,

2000). Another way to develop task commitment is to always build upon the child’s strengths

(Renzulli, 1986). Renzulli (2005) writes,

The task of providing better services to our most promising young people cannot wait

until theorists and researchers produce an unassailable, ultimate truth. Such truths

probably do not exist. But the needs and opportunities to improve truths probably do not

exist. But the needs and opportunities to improve educational services for these young

people exist in countless classrooms every day of the week. (p. 274)

Gagne. Gagne’s Differentiated Model of Talent differentiates between giftedness and

talent. With this model the two terms cannot be used interchangeably as they often are. Gagne

(1985, 1993,1998,1999a, 1999b, 1999b, 2013) views giftedness as being natural ability or

potential. Talent is the product of intervention (Gagne, 2013). Gagne’ believes different catalysts

can promote management between the domains of the product of intervention (Gagne, 1985).

Gagne’ believes different catalysts can promote giftedness and talent (Gagne, 2013). His model

presents five Aptitude domains: creative, intellectualization, sensorimotor, socio-affective and

others (Gagne, 1993, 1999a, 2013). By examining the child’s achievements, it can be determined

if the child is gifted. The environment serves as a catalyst as this process occurs. Not all children

are exposed to the same nurturing environment and chance may play a role in determining who

will reach their full potential. Moon (2007) believes Gagne’s theory is considered by many to be

39

the most comprehensive and the most valid theories of giftedness. Children who do not feel safe

and supported may not develop to their potential, impacting society in a devastating way.

Gardner. Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences has been quite popular in

the field of education, peaking perhaps in the late 1980s. His approach (1983, 1991, 1993, 1995,

1999) is quite unique in the concept moves the focus of identifying giftedness from a single

approach to a multi-category approach. The term ‘intelligence’ refers to a special ability, talent, or

skill which allows individuals to maximize their potential by building on the specific strength he

or she demonstrates. The multiple intelligences strongly parallels using preferred learning styles

(Campell, Campbell, & Dickinson, 1992). Armstrong (1987, 1994) sheds light on Gardner’s

Multiple Intelligences Theory by noting each child possesses aspects of all eight intelligences and

is challenged to develop them to a fairly high level of competence. Gardner believes by the time a

child begins school, he or she will have established ways of learning which tend to favor some

intelligences more than others (Gardner, 1983). The identification of which intelligences a child

has favored is not a simple process. Gardner does not suggest students need to master all eight

intelligences or focus on gaps in their learning (Gardner, 1995). As Gardner’s (1983, 1993, 1995)

multiple intelligences are applicable, to some degree, to all students, this model is not especially

suitable for meeting the needs of gifted students. Only three of Gardner’s intelligences may be

measured on traditional intelligence tests (Eckert, & Robins, 2016; Moon, 2006a, 2006b). Critics

of Gardner argue his concept appears to be a form of differentiation (Eckert, & Robins, 2016).

The argument is if teachers are differentiating for all students then they still are not stretching or

challenging those high potential and profoundly gifted students in ways which are pressingly

needed. which are pressingly needed.

40

Scott Barry Kaufman, (2018) points out these theories, although influential, are static. He

cautions these theories or concepts do not tell us how these important traits are developed across a

life span. Kaufman asks, (2018) “How do ability and motivation for example get converted to

real-world achievement? Are environmental factors more important or does success need to come

from within an individual?” (p. 78).

Other Relevant Conceptions of Giftedness

A lesser known model, which may have significance when applied to the topic of bullying

and giftedness, evolved from the positive psychology movement and is known as Operation

Houndstooth (Renzulli, Koehler, & Fogarty (2006). This model emerged from Renzulli’s Three-

Ring Conception. The result is known as socially constructive giftedness which seeks to

understand the reason a student uses their talents to help another or contributes to social capital.

Renzulli describes social capital as intangible assets to address the collective needs of individuals

and communities. The work of Renzulli et al. (2006) shows this form of capital, social capital, has

sharply declined in recent years as demonstrated by low participation in civic clubs, church

groups, parent-teacher associations, and service clubs. This framework contains several

components: Optimism, Courage, Romance with a Topic of Discussion, Sensitivity to Human

Concerns, Physical/Mental Energy and Vision/Sense of Destiny. Renzulli and colleagues describe

social capital as intangible assets to address the collective needs of individuals and communities.

Unlike the other concepts, Operation Houndstooth is not a static definition and may

answer Kaufman’s question of how motivation and environment get converted to real world

achievement, or to higher levels of social responsibility. This specific conception the authors

illuminate may be relevant for a gifted child who witnesses another student being bullied. The

gifted child may act to support and include the victim in the community and may work to remove

41

any barriers or reasons for a child to be bullied using the framework established. Both the victim

and the gifted child are benefitting. A safer and stronger community could be the result (Renzulli

et al., 2006).

Asynchronous development. A more recent look at giftedness comes from the work of

Linda Silverman, the Director of the Institute for the Study of Advanced Development, Colorado

Gifted Center. Silverman included asynchronous development in her definition which is the

uneven development of gifted children. Asynchrony is the term used to describe the mismatch

between cognitive, emotional, and physical development of gifted individuals (Silverman, 1997,

2009, 2012). A gifted individual may be able to explain string theory but may struggle

developmentally to tie the strings on his or her shoes. Silverman argues IQ and emotional traits

should also be considered (Silverman, 1997).

Columbus group definition. A group of parents, educators, administrators and counselors

used the work of Silverman (1997), the work of Hollingworth (1914, 1926, 1942), as well as the

work of Jean-Charles Terrassier (2011) when developing a more current definition of giftedness:

Giftedness is asynchronous development in which advanced cognitive abilities and

heightened intensity combines to create inner experiences and awareness that are

qualitatively different from the norm. This asynchrony increases with higher intellectual

capacity. The uniqueness of the gifted renders them particularly vulnerable and requires

modifications in parenting, teaching, and counseling for gifted students/individuals to

develop optimally.

State definitions and federal definition. Individual states have varying definitions and